During the War

"Like a destructive storm, the war struck suddenly and spread rapidly. Everything was confusion. It was difficult to know who was friend and who was foe."

"Like a destructive storm, the war struck suddenly and spread rapidly. Everything was confusion. It was difficult to know who was friend and who was foe."

Mahipiyatowin, or Esther Wakeman, a Mdewakanton relative of Little Crow and witness to the war, as told to her daughter Elizabeth.

The war was fought primarily by Mdewakanton and Wahpekute men. Of the estimated 6,500 Dakota people living on Minnesota reservation land in 1862, historians think no more than 1,000 actually fought, including some who were coerced into the battles.

Before the war broke out, a group of Mdewakantons had formed a soldiers’ lodge. Traditionally, the soldiers’ lodge regulated hunting efforts within a village. Increasingly, though, this lodge attracted young men who resisted U.S. assimilation policies. Dakota farmers were not allowed to join.

Timeline of War:

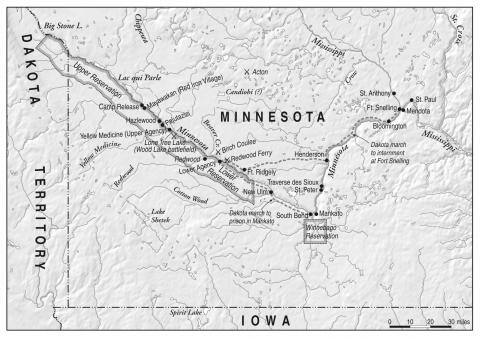

August 17: Four young Dakota men murder five white settlers near Acton Township, Meeker County. Fleeing to their village, they beg for protection. Leaders of the soldiers’ lodge appeal to Little Crow (Taoyateduta) to lead them in war on the whites. Reluctantly, he agrees.

August 18: Mdewakanton warriors open fire on white traders and government employees at the Lower Agency and defeat a relief force sent from Fort Ridgely. Dakota warriors attack isolated farms and settlements in Renville and Brown counties.

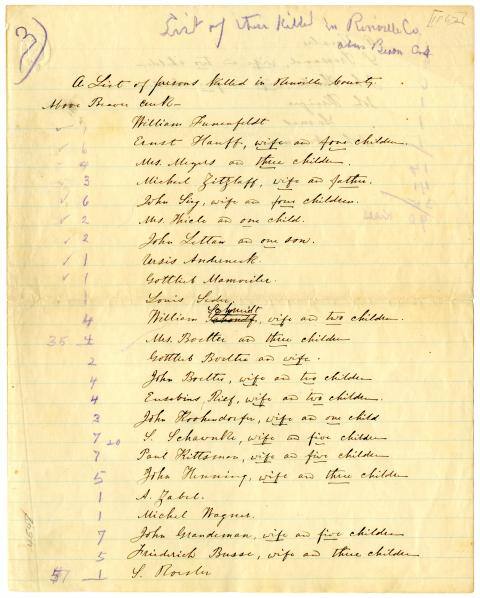

There are an estimated 1,200 settlers in Renville County in 1862. On the 18th and 19th, more than 160 residents are killed; more than 100 more are taken captive. With few exceptions, the bodies of those who died are in unmarked graves, where they fell.

Milford Township also suffers many losses. Located just west of New Ulm in Brown County, Milford Township is populated by mostly German immigrants. More that 50 residents are killed, making it one of the hardest-hit communities during the war.

In all, more than 200 settlers are killed in these raids, and more than 200 women, children, and mixed-race civilians are taken hostage.

August 19: The Upper Agency is evacuated and its white inhabitants are led to safety by Aƞpetutokec̣a (John Other Day). News of events at the Lower Agency reaches St. Paul; Gov. Alexander Ramsey commissions Henry H. Sibley, a former trader, congressman, and governor, to lead a force of volunteer state militia against the Dakota. As thousands of refugees begin arriving in eastern Minnesota towns, bearing tales of atrocities real and imagined, panic sweeps the state.

New Ulm comes under seige by a relatively small group of Dakota warriors. This skirmish lasts several hours and leaves five settlers dead. The following day the people of New Ulm elect Judge Charles Flandreau, a prominent citizen from St. Peter, as their military commander. Over the next few days more than 1,000 refugees balloon New Ulm's population to 2,000 people, while only 300 are equipped to fight.

August 20-22: The Dakota make two attacks on Fort Ridgely and are turned back. The Lake Shetek settlement is attacked, and the women and children taken hostage are carried into Dakota Territory. An attack at West Lake (Norway Lake or present-day Monson Lake) occurs, killing 13 people.

August 23: The second battle of New Ulm. This time, more than 600 Dakota soldiers fight under the guidance of Chiefs Waŋbdí Tháŋka, Wabaṡa, and Makato. This is the largest battle over a US town since 1776. After holding off the attack, Charles Flandreau leads the evacuation of new Ulm on August 25, leaving much of the city in ashes. Little Crow’s camp retreats to the upper reservation.

August 25: Missionaries fleeing from the vicinity of the Upper Agency reach Henderson safely.

August 26: Upper Dakota men form a soldiers’ lodge to oppose the war, crystallizing the Dakota Peace Party.

August 28: The force led by Sibley reaches Fort Ridgely, where some 350 refugees who have been under siege for ten days are gathered.

September 2: A burial party sent out by Sibley is attacked at Birch Coulee. The Peace Party opens negotiations with Sibley.

September 3-4: A Dakota force led by Little Crow fights a skirmish at Acton and attacks barricaded settlements at Forest City and Hutchinson. Fort Abercrombie on the Red River is attacked and surrounded. Sibley learns that the Dakota hold more than 250 hostages; he begins negotiating for their release.

September 18: Sibley’s forces leave Fort Ridgely and advance up the Minnesota River Valley.

September 23: Sibley defeats a Dakota force led by Little Crow at Wood Lake near the Yellow Medicine River. A relief force sent from Fort Snelling by way of St. Cloud reaches Fort Abercrombie.

September 24: Little Crow and his followers flee westward.

September 26: The Dakota Peace Party surrenders hostages at Camp Release.

County-by-county breakdown of events:

Theme:

1862Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at Copyright and Use Information.

Bibliography

Carley, Kenneth. The Dakota War of 1862: Minnesota’s Other Civil War. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1976.

Cox, Hank H. Lincoln and the Sioux Uprising of 1862. Nashville, TN: Cumberland House Publishing, Inc., 2005.

Dahlin, Curtis A. The Dakota Uprising. Edina, MN: Beaver’s Pond Press, 2009.

Diedrich, Mark. Little Crow and the Dakota War. Rochester, MN: Coyote Books, 2006.

Resources for Further Research

Multimedia

A Clash of Cultures: Understanding the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862. AMPERS.

Fort Snelling and the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862.

www.usdakotawarmncountybycounty.com

Primary

Anderson, Gary and Woolworth, Alan. Through Dakota Eyes: Narrative Accounts of the Minnesota Indian War of 1862. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1988.,>

Deloria, Ella. The Dakota Way of Life. Sioux Falls, SD: Mariah Press, 2007.,>

Derounian-Stodola, Kathryn Zabelle. The War in Words: Reading the Dakota Conflict Through the Captivity Literature. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2009.

Eastlick, Lavinia. Thrilling Incidents of the Indian War of '62: Being a Personal Narrative of the Outrages and Horrors Witnessed by Mrs. L. Eastlick in Minnesota. Mankato, MN: Free Printing, 1890.

Oman, A.P. "Childhood Memories." Willmar Daily Tribune. August 29, 1935.

Wakefield, Sarah F. Six Weeks in the Sioux Teepees a Narrative of Indian Captivity. Shakopee, MN: Argus and Job Printing Office, 1864.

Secondary

Anderson, Gary Clayton. Little Crow: Spokesman for the Sioux. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1986.

Carley, Kenneth. The Dakota War of 1862: Minnesota’s Other Civil War. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1976.

Cox, Hank H. Lincoln and the Sioux Uprising of 1862. Nashville, TN: Cumberland House Publishing, Inc., 2005.

Dahlin, Curtis A. The Dakota Uprising. Edina, MN: Beaver’s Pond Press, 2009.

Diedrich, Mark. Little Crow and the Dakota War. Rochester, MN: Coyote Books, 2006.

Kostash, Myrna. A Tale of Two Massacres: The haunting parallels—and striking differences—between a pair of Native uprisings. Literary Review of Canada, 2012: http://reviewcanada.ca/essays/2012/12/01/a-tale-of-two-massacres/

Nichols, David A. Lincoln and the Indians: Civil War Policy and Politics. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1978; reprinted 2012 by the Minnesota Historical Society Press

Key People

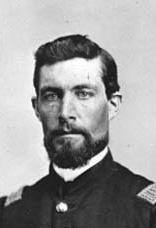

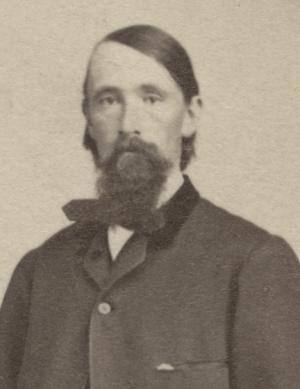

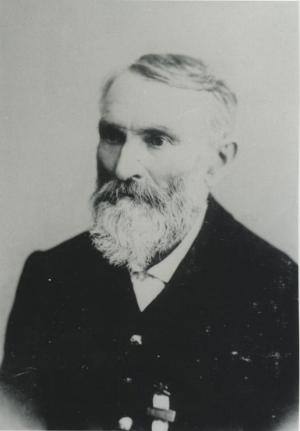

Timothy J. Sheehan

Timothy J. Sheehan as born in Ireland in 1836. He was 14 years old when he came to the US. He was a mechanic in New York until 1855, and worked at a sawmill in Illinois. By 1856, he lived in Albert Lea, Minnesota, where he was a farmer. At the time of the Civil War, he enlisted in the army, and became a Corporal in Company F, 4th Minnesota Infantry in 1861. He was promoted to First Lieutenant in Company C, 5th Minnesota Infantry on March 9, 1862.

Company C began garrison duty at Fort Ripley and Sheehan was then sent to Fort Ridgely, along with 50 other men. Captain Marsh was their commander at post. On June 29, 1862 the detachment was sent to the Upper Sioux Agency to maintain order during the event of a late annuity payment from the U.S. government to the Dakota, where Sheehan goaded Galbraith into distributing food, after much disagreement. On August 18, Sheehan was headed to Fort Ripley to accompany Indian Commissioner William P. Dole with a treaty between the United States and the Ojibwe. Receiving a message from Captain Marsh at Fort Ridgely requesting aid due to Dakota attacks, Sheehan and his men rode to help. After Marsh was killed, 2nd Lt. Thomas P. Gere had become post commander. Sheehan then took over command, and helped successfully defend the fort from attack on August 20 and 22 until reinforcements arrived. He then rode out to assist the battle at Birch Coulee alongside Colonel Samuel McPhail--riding again between there and the Fort to request further reinforcement for that battle.

He was promoted to Full Captain on August 31, 1862. After completing services at Fort Ripley, Sheehan and the rest of Company C joined the rest of the 5th Minnesota Regiment on December 12 in Mississippi to fight against Confederate troops. Under the leadership of Sheehan, they participated in the Siege of Vicksburg, the Battle of Nashville, the Siege of Spanish Fort and Fort Blakely in Alabama, and the Battle of Tupelo in Missouri.

Sheehan was promoted to lieutentant colonel on September 1, 1865, but mustered out of service a few days later at Fort Snelling. He returned to Albert Lea, and was appointed Deputy U.S. Marshal. Marrying Jennie Judge, he had three sons and served as Freeborn County sheriff for more than ten years.

In October 1895, he was wounded in the Battle of Leech Lake, also known as the Battle of Sugar Point, between the Pillager band of Ojibwe and U.S. troops--considered the "last of the Indian uprisings," coming nearly five years after the Battle of Wounded Knee at Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota.

By 1900, he and his family had moved to St. Paul, where he died in 1913.

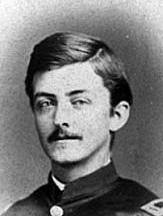

Thomas P. Gere

Lieutenant Thomas P. Gere was born in 1842 in Wellsburg, New York. He enlisted in the 5th Minnesota Volunteer Infantry Regiment at age 19, mustering in on January 17, 1862. He was promoted to first sergeant on March 5 of that year and then to second lieutenant on March 24. He later became first lieutenant and adjutant.

He was nineteen years old and based at Fort Ridgely in 1862 when the U.S.-Dakota War broke out. On the morning of August 18, he was in charge at the fort when Capt. John Marsh left to see about reports coming from the Lower Sioux Agency about Dakota attacks. Commanding 25 soldiers, and caring for hundreds of terror-ridden refugees fleeing attacks, Gere Gov. Ramsey and Fort Snelling asking for reinforcements. Organizing his soldiers and some refugees to prepare for attack, he awaited help. He was finally joined by Sheehan and his soldiers, along with Indian Agent Galbraith and the Renville Rangers, and the fort held out for the next ten days.

Gere later fought in the Civil War. He was awarded the Medal of Honor in 1865 for his actions at the Battle of Nashville in 1864. He mustered out of the military in 1865 and began work in the railroad business. He died in 1912 and was buried in Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia.

Chaska

In August of 1862, at the start of the U.S.-Dakota War, Chaska, or Wechankawastadonpe, a Dakota man, and his campanion, Hapan, came across Sarah Wakefield fleeing in an acquaintance's wagon from the Lower Sioux Agency.

Deciding to spare Wakefield after Hapan killed Mr. Gleason--the wagon owner--Chaska took her and her children under his protection throughout the six weeks of battles. Moving them in with his family, he claimed he wished to marry Wakefield to keep her safe from any perceived harm. A trust and respect relationship developed between him, his family, and Wakefield. At the end of the war, Chaska released Wakefield at Camp Release. Wakefield urged Chaska and his family to remain, reassuring them that they would be treated fairly. About his protection she said, "If it had not been for Chaska my bones would now be bleaching on the prairie".

Despite her claims defending Chaska, made publicly and during the ensuing trials of Dakota men involved in the war, Chaska was imprisoned and initially sentenced to be hanged. Rumors about her and Chaska's relationship incited prejudiced opinions. At one point, General Sibley referred to Chaska as Wakefield’s lover.

After having his sentence commuted to a prison term, Chaska nevertheless ended up being among the 38 hanged in Mankato. There is dispute over whether this was accidental or purposeful. Stephen Riggs asserted that the error occured when Chaska's name was called and he stood up instead of the intended man, Chaskadon. Wakefield disputed this point and said, "I will never believe that all in authority at Mankato had forgotten what Chaska was condemned for, and I am sure, in my own mind, it was done intentionally."

After his death, Chaska's body was hastily buried with the other victims. It was then exhumed by doctors to be used for dissection.

Reactions after the hanging allude to the flurry of opinion surrounding the "scandal" between Chaska and Wakefield. In a letter to J. Fletcher Williams, secretary of the Minnesota Historical Society, J. K. Arnold described how he came into possession of a noose from the Mankato hangings.

Dear “Fletch,”

Your acknowledgment rec’d “OK.” Many Thanks. Only when your next meeting comes off have the resolution acknowledging receipt of the document be made to the “Seventh Regiment, Minn Infty thro’ J. K. Arnold Adjutant __.”

I fw’d to day the rope, original with knot and noose just as it was taken off from Chaska’s head. It has never been untied, and is, as it was taken from his neck. I stole it. Col. Miller was going to send them all (38) to Washington, but I wanted this one which hung Chaska. I took it off his neck hid it under my coat, went to my room. Hid it under my blankets (bed) and slept on it until the excitement was over for the missing rope, when I shipped it home by Express, since which I have carefully preserved it. “Old Steph” made an awful fuss about it wondering what could have become of it, he __ does not know to this day that his Adjutant had the same.

Well enough. Accept it, from your friend. And—one word more. Any thing—Relics—Statistics or wh____ you wish I can furnish. Call upon

Your Friend (I hope)

J. K Arnold

This is a photo of Lincoln's Execution List, 1862.

Sarah F. Wakefield

Sarah Brown was born in Rhode Island in 1829 and came to Minnesota in 1854 where she met her husband Dr. John L. Wakefield whom she married in 1856 and had two children. Dr. Wakefield was a land speculator, legislator, and had a medical practice in Shakopee, Minnesota.

The Wakefields moved to Blue Earth City and were among the earliest settlers there. Dr. Wakefield was appointed physician at Yellow Medicine (Upper Sioux Agency), where they were when the U.S.-Dakota War began. Upon hearing about the war, Mrs. Wakefield and her children fled and were taken prisoner on their way to Fort Ridgely. A Dakota man named Chaska (Wechankwastadonpe) and his family took them under their protection throughout the six weeks of battle. They were safely returned at Camp Release after the war. She urged Chaska and his family not to flee, reassuring them that they would be treated fairly. About Chaska's protection she said, 'If it had not been for Chaska my bones would now be bleaching on the prairie, and my children with Little Crow."

Chaska was among those whose sentence was commuted during the trials after the war, largely in part due to the testimony of Wakefield. She was harangued by the media for defending Chaska, and rumors flew about their relationship. At one point, General Sibley, who was involved with the trials and convictions after the war, referred to Chaska as Wakefield's lover. Nevertheless, Chaska ended up being among the 38 hanged in Mankato. There is dispute over whether this was accidental or purposeful. Stephen Riggs asserted that the error occured when Chaska's name was called and he stood up instead of the intended man, Chaskadon. Wakefield disputed this point and said, "I will never believe that all in authority at Mankato had forgotten what Chaska was condemned for, and I am sure, in my own mind, it was done intentionally."

After her husband's death in 1874, Wakefield moved to St. Paul, Minnesota, where she died in 1899.

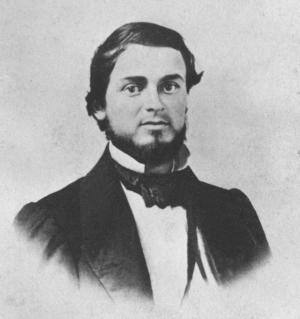

Charles Flandreau

“Their advance upon the sloping prairie in the bright sunlight was a very fine spectacle, and to such inexperienced soldiers as we all were, intensely exciting.”

Charles Flandreau

On the afternoon of August 19, 1862, New Ulm came under siege by a relatively small group of Dakota warriors. This skirmish lasted several hours and left five settlers dead. The following day the people of New Ulm elected Judge Charles Flandrau, a prominent citizen from St. Peter, as their military commander. Over the next few days more than 1,000 refugees ballooned New Ulm’s population to 2,000 people, while only 300 were equipped to fight.

The second battle of New Ulm took place on August 23. This time, however, more than 600 Dakota soldiers fought, under the guidance of Chiefs Waƞbdiṭanka, Wabaṡa, and Makato. This was the largest battle over a US town since 1776. After holding off the attack, Charles Flandrau led the evacuation of New Ulm on August 25, leaving much of the city in ashes.

Ellen McConnell

living near Birch Coulee with her son, David, when the war broke out. On the late afternoon of August 18, Ellen was alone in her house when two Dakota men broke in. Ellen was unharmed during the attack, but her 13-year-old grandson (Thomas Brooks) was killed and her daughter (Martha Clausen) and infant grandchildren were captured. Her son-in-law, Fred, and his father, Charles, were also killed. Martha Clausen witnessed the murder of her husband.

The day after the attack, Ellen and David began walking to Fort Ridgely, 12 miles away. There they met Ellen’s other son, Joseph, who had been working as a plasterer at the Lower Agency and escaped on the morning of the attack. They were at Fort Ridgely during both battles that took place there.

Ellen never returned to Birch Coulee. She received $112 in compensation for the belongings listed on her depredation claim, including a family Bible. She and David moved to Houston County, where she died in 1868.

Generations of settler families were affected by the war. All were forced from the land they worked so hard to improve. My great-great-grandmother’s mind was ‘shattered,’ according to historical reports, and she was never the same after her losses.

--Mary McConnell, 2012

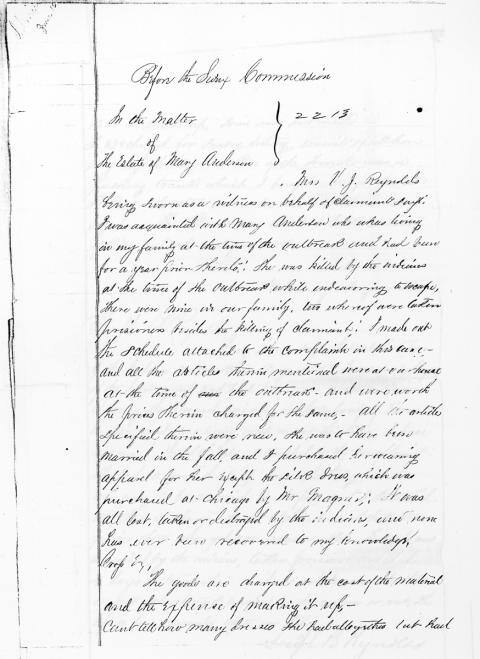

Mary Anderson

When the war began, Mary Anderson was a housekeeper living near the Lower Sioux Agency with the family of Joseph B. Reynolds. The family was attacked by the Dakota at the Lower Agency. Mary was shot while trying to escape, and died in capitivity a few days later. The Reynold's niece, Mattie Williams, and Mary Schwandt were taken prisoner at the same time. Mary Anderson's depredation claim was filed by the family of Joseph B. Reynolds and is comprised mostly of dresses and clothing, which had been made in preparation for her upcoming wedding.

"I was awake when she died, and she dropped away so gently that I thought she was asleep, until Mattie told me she was dead. . . . Joseph Campbell, a half-breed, assisted us in having her buried. Mattie and I saw her carried to the grave by the Indians, wrapped in an old piece of tepee-cloth, and laid in the ground near Little Crow’s house. She was subsequently disinterred, as I am informed, and buried at the Lower Agency. A likeness of a young man, to whom she was to have been married, we kept and returned to him; and her own we gave to Mrs. Reynolds, who yet retains it."--Mary Schwandt, recalling Mary Anderson’s death, 1864

Roseanna Webster

"So far as she knows she has no brother or sister living--never having had any children, and is almost alone in the world--that she is the only heir to her husband’s estate."

Roseanna Websters Depredation Claim, 1863

In the weeks before the war, Viranus and Roseanna Webster had been living in their wagon near the Baker home in Acton Township, Meeker County, looking for land to purchase. On August 17th, they were at the Baker residence when four young Dakotas opened fire and killed five settlers, including Roseanna’s husband, Viranus. She fled to St. Paul, but had to leave all her belongings in Acton.

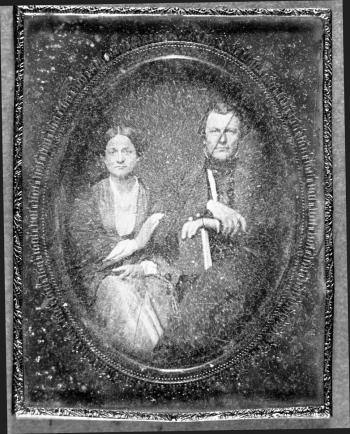

The Kochendorfer family

Johann and Catherine Kochendorfer settled with their children in Flora Township, Renville County, in April 1862. On August 18, Johann, Catherine, and their baby, Sarah, were all killed in an attack on their homestead. Johann lived long enough to motion to his children — John, age 11, Rose, age nine, Kate, age seven, and Margaret, age five — to hide in the brush until the attack ended. The children then walked about 11 miles before meeting up with neighbors, all of whom eventually reached Fort Ridgely safely.

The family, from left: Catherine holding Margaret, John, Johann holding Kate, and Rose, about 1860.

Courtesy Brown County Historical Society, New Ulm, MN

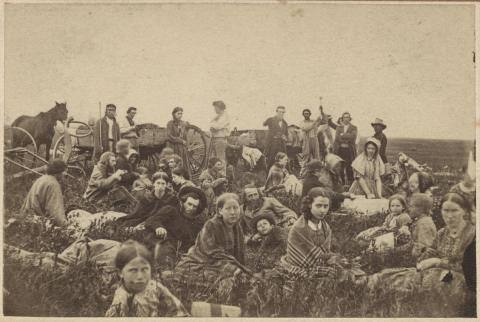

Missionary Party

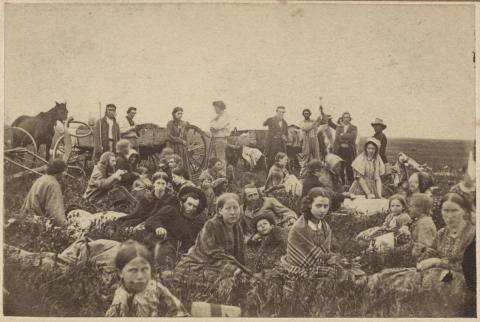

On August 19, a group of about 35 missionaries, mission workers, and government employees fled from the Upper Agency. They headed first toward Hutchinson, then rerouted toward Fort Ridgely.

Adrian Ebell escaped with this party, and took their photo during a breakfast break. It is the only extant photo taken during the war.

Richard Orr was injured when Dakota attacked his trading post at Big Stone Lake and killed his partner. Stephen Riggs wrote that “our wagons were more than full, but we could make room for a wounded white man.” When the party reached safety, Orr went to St. Peter, where he was hospitalized for two months.

Mr. and Mrs. D. Wilson Moore were visiting Minnesota on their honeymoon and had come to the Upper Agency to observe the process of annuity payments. After reaching safety, the Moores took a steamboat to St. Paul, then returned home to New Jersey.

Stephen Riggs was a longtime missionary to the Dakota. His wife, Mary, and their children Cornelia, Isabella, Robert, Thomas, Henry, Anna, and Martha are also in the photograph.

Sophia Robertson was the daughter of Andrew Robertson and his wife, Jane, the granddaughter of Grey Cloud, and the great-granddaughter of Wabasha.

Elizabeth (Williamson) and Andrew Hunter: Elizabeth was the daughter of Dr. Thomas Williamson.

Hugh and Mary Cunningham were houseparents for the boarding school at Stephen Riggs’s Hazelwood mission. Hugh’s sister Martha was also with the party.

Henry and Nancy Williamson were the children of Dr. Thomas and Margaret Williamson.

Jonas Pettijohn, a former teacher in the government school at Red Iron’s village (12 miles northwest of Riggs’s mission), was moving his family to St. Peter when war broke out. His wife, Fanny, and children Alice and William were also with the party.

This photo was taken on August 21, 1862 by Adrian Ebell.

Harriet Dodd

In 1853, William B. Dodd claimed 150 acres near the Minnesota River, where he founded the town of Rock Bend (now St. Peter). On August 23, 1862, Dodd was killed in battle at New Ulm. His wife, Harriet, kept a diary that captures the uncertainty and mayhem of the first week of the war.

1862 Aug. 19. W.B. Dodd left his home before daylight to prepare to march to defence [sic] of New Ulm.

20. Armed men constantly passing through St. Peter.

22. Burning at Norwegian settlement. Great panic among the citizens of St. Peter all rushing into the warehouse.

25th Monday. Heard the rumor that he was killed but did not believe it.

26 Tuesday. The Kiniff boy came and told me he helped to bury him!

27 on Wednesday Dr. Daniels came and brought me his last words. Last--oh shall I never never more hear his voice?

Two weeks after her husband had been killed, Harriet Dodd recorded her son Johnny's reaction to the news of continued violence:

Sept. 11, Thursday. To day Johnny is complaning, how my heart yearns toward this "father's child" I wish I could have dagguerotyped his countenance and attitude as he said yesterday 'Mamma, I'm not afraid, I'll stay by you. If Indian come, I'll chop his head right off.' and illustrating his words, he chopped one tiny finger on the other hand with a most decided movement. Tonight he is a little feverish, and says, 'Do the Indians hurt you? They hurt papa and I must shoot 'em I'm not afraid.'

Anna Jane Riggs

Anna Jane Riggs was the 17-year-old daughter of missionary Stephen Riggs. She lived with her parents and siblings at their mission Hazelwood on the Upper Reservation in Minnesota. She was planning on attending finishing school in the east. In this photo, taken by Adrian Ebell, she was fleeing on the prairie with a group of missionaries during the U.S.-Dakota War.

View full article: Anna Jane Riggs

The William Luskey Family

"On August 19, pleas for assistance in fighting the Dakota War reached Le Sueur County. About 150 settlers responded. Calling themselves the Le Sueur Tigers, they formed two companies and marched to New Ulm."

William Luskey, an Irish immigrant, joined the Tigers along with several of his close neighbors. On August 23, during the second battle of New Ulm, six Tigers were killed, including William Luskey and his neighbors Matthew Ahern and William Maloney. The three men left behind their wives and a total of 13 young children.

With the deaths of the Tigers, it became extremely hard for the surviving young widows and children to physically carry on. The tasks the men performed on a daily basis on their farms were now assigned to their wives and young children.

The oldest of the surviving children was eight years old. The children took a leading role in the months and years following the war. The hard physical labor they had once done on occasion by helping out their parents now became a daily way of life.

They all grew into adults, eventually raising their own children, but the thought of their younger days was never far from their minds and hearts.

I am proud to be one of their descendants.

George Luskey, 2012

Wakandayamani (George Quinn)

George Quinn was born in 1843. His mother was Ineyahewin, a Mdewakanton Dakota. George Quinn was visiting the Redwood Agency when war broke out. In 1898 he told his story to newspaper reporter Return I. Holcombe:

I am half white man and half Indian, and I learned to read and write the Sioux language at Lake Calhoun under the instruction of the Pond brothers. But I never learned to speak English and I was raised among the Indians as one of them. So when the outbreak came I went with my people against the whites. I was 19 years old and anxious to distinguish myself in the war, but I had no wish to murder anyone in cold blood, nor did I; nobody ever accused me of such a thing. I fought the white soldiers, but not the unarmed white settlers.

After the war, George Quinn was tried and convicted by the military commission that sentenced 303 Dakota men to hanging. He received a reprieve and was sent to prison in Davenport, Iowa, until he was pardoned in 1866. He then moved to the Santee Reservation in Nebraska Territory. He died at Morton, Minnesota, in 1915.

Snana and Mary

The lives of Mary Schwandt, a 14-year-old German American, and Snana (Maggie Brass), a 23-year-old Dakota woman, became intertwined during the war. Mary’s parents and all but one of her six siblings were killed in Renville County on August 18. Mary was taken captive by a soldier from the Lower Sioux reservation.

Maggie’s seven-year-old daughter, Lydia, had died six weeks before the war broke out. Maggie arranged to have Mary Schwandt released from her captors, and then protected her from harm for the remainder of the war by hiding her and dressing her in Dakota clothing. Each of the women later wrote a memoir; in hers, Mary wrote to Maggie, “I want you to know that the little captive German girl you so often befriended and shielded from harm loves you still for your kindness and care.”

John Jones

John W. Jones was a combat-wounded veteran of the Mexican War (1846-47) who in 1862 was serving as ordnance sergeant at Fort Ridgely. In charge of the government artillery there, he trained soldiers of the Fifth Minnesota Infantry garrison. During the two battles at Fort Ridgely, the artillery was instrumental in holding off an overwhelming number of Dakota soldiers. After the battles at Fort Ridgely, Jones made this list of the casualties as part of his report to superiors.

Sgt. Jones was later commissioned captain of the Third Battery, Minnesota Volunteer Artillery, and served on the 1863 Sibley Expedition and the 1864 Northwestern Indian Expedition.

.jpg)

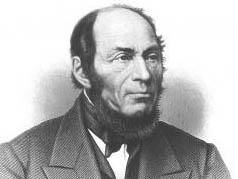

Joseph R. Brown

Joseph Renshaw Brown was born in York County, Pennsylvania, on January 5, 1805.

After enlisting in the U.S. Army in 1820, he was assigned to the Fifth Infantry Regiment, which had been sent to the upper Mississippi River area in order to build a military post at the river's confluence with what is now known as the Minnesota River. The post--Fort St. Anthony--was later renamed Fort Snelling. After leaving the army in 1828, Brown remained in the area, and in the ensuing years he was at various times a fur trader farmer; lumberman; stagecoach line owner; justice of the peace, clerk of court, and register of deeds; printer; newspaper editor, owner, and publisher; and U.S. Indian agent in Minnesota (1857-61).

Actively involved in politics, he served in the Wisconsin Territorial Legislature, as a delegate to the conventions that organized Minnesota Territory and drafted the state's constitution, and in the Minnesota Territorial Council and Legislature. He was also an avid promoter of a steam-powered traction engine which he purchased from a New York engineer. Brown was associated with the development of several Minnesota communities, including the town of Henderson.

In 1850, the twice-divorced Brown married Susan Frenier, whose forebears included a French fur trader, a Mdewakanton Dakota chief, and a Yankton Dakota chief.

During the U.S.-Dakota War, while he was away from Minnesota on business related to the steam wagon, Brown's house near what is now the town of Sacred Heart was burned and his family captured. They were later released. Following his return to Minnesota he served as superintendent of the Indian prison at Mankato, participated in the military campaigns against the Dakota, and was special military agent at Fort Wadsworth, Dakota Territory. He died in New York City in 1870, while on a business trip in connection with the steam wagon. <

For more information, see: Nancy Goodman and Robert Goodman, Joseph R. Brown: Adventurer on the Minnesota Frontier, 1820-1849, Rochester, MN: Lone Oak Press, 1996

Tiwakan (Gabriel Renville)

Tiwakan (Sacred Lodge), also known as Gabriel Renville, was born in 1825 to "mixed-blood" (individuals of both European and Dakota ancestry) parents but was raised by his stepfather Joseph Akipa Renville, a Dakota man. By 1860 he had settled on a farm near the Minnesota River. When the war started, Tiwakan helped organize the "Peace Party" in opposition to the war, and worked to secure the release of the prisoners captured by Dakota soldiers. After the end of the war he and his family were sent to the internment camp for civilians at Fort Snelling, and from 1863 to 1866 Tiwakan served as a scout for the Punitive Expeditions into the Dakota Territory. Tiwakan later became a leader on the Sisseton Reservation, eventually returning to Minnesota where he died on August 26, 1892.

During the War:

"When we had gone about a mile and a half, we came to where the hostile Indians had formed a camp. As we were passing through the camp, I saw many white prisoners, old women, young woman, boys and girls, bareheaded and barefooted, and it made my heart hot, and so I said to Ah-kee-pah, Two Stars, and E-nee-hah, 'If these prisoners were only men, instead of women and children, it would be all right, but it is hard that this terrible suffering should be brought upon women and children, and they have killed many of even such as these.' I therefore had in mind to call a council, invite the hostile Indians, and appoint Mazo-ma-ne and Marpiya-wicasta (Cloud Man) to say to the hostiles that it was our wish that the prisoners should be sent home. Ah-keep-pah, Two Stars, and E-nee-hah, agreed with me in my idea, and they told me to go on and do so."

On imprisonment at Fort Snelling:

"They [the Dakota non-combatants] were then taken down on the east side of the Minnesota river, and went into camp at some distance from Fort Snelling. Shortly after this the camp was moved again, being located close to the Minnesota River. These camps were always well guarded, but in spite of that many of the horses and oxen belonging to the Indians were stolen, including three horses that belonged to myself and Charles Crawford [Gabriel’s half brother]…. Then a fence was built on the south side of the fort and close to it. We all moved into this inclosure [sic], but we were so crowded and confined that an epidemic broke out among us and children were dying day and night, among them being [Solomon] Two Stars’ oldest child, a little girl. . . . The news then came of the hanging at Mankato. Amid all this sickness and these great tribulations, it seemed doubtful at night whether a person would be alive in the morning. We had no land, no homes, no means of support, and the outlook most dreary and discouraging. How can we get lands and have homes again, were the questions which troubled many thinking minds and were hard questions to answer."

Philander Prescott

Philander Prescott was born September 17, 1801 in Phelpstown, New York. In 1820 he arrived at Camp New Hope (Fort Snelling) in Minnesota. He married the daughter of a Dakota chief in 1823. Prescott and his wife, Mary, and their children lived among the Dakota for more than 40 years. He was engaged in the fur trade with the American and Columbia fur trading companies and was associated with Lawrence Taliaferro's Eatonville agricultural colony for the Indians. He was an interpreter during the Traverse des Sioux treaty negotiations in 1851.

Prescott talked about treaty funds being misused in a report made to the Bureau of Indian Affairs in 1856:

"Estimates and requisitions have annually been made from the Sioux agency office for all the funds due the Sioux by treaty stipulations.

To the honor of the president and congress these funds to the full extent have been annually appropriated. And when it was represented a few years ago that an earlier payment of the annuities would be desirable these appropriations have been since made one year in advance. Have the officers under the president applied these funds, so appropriated in the manner stipulated by the treaties? I can distinctly say no!

The treaties say these funds shall be annually expended, whereas large amounts have been kept back and are now in arrear and that after repeated applications to have them expended. These arrears are not mere petty sums, surpluses or remnants of funds remaining unexpended but large amounts thousands and tens of thousands-and in some cases the whole fund appropriated for a special purpose.'"

On the morning of August 18, 1862, Dakota friends warned Prescott to stay out of sight in his house. His family stayed there, but Prescott chose to flee to Fort Ridgely. Dakota soldiers killed him and took Mary, his wife, and their children captive. Mary and her daughter Julia escaped captivity during the Battle of Wood Lake and went to Fort Ridgely.

Andrew Myrick

"So far as I am concerned, if they are hungry let them eat grass or their own dung."

Andrew Myrick to Agent Galbraith, 1862.

Andrew Myrick was born in 1832. He was a trader at the Lower Sioux Agency at the time of the U.S.-Dakota War and is often considered in part responsible for the start of the war. When Dakota leaders asked the traders to extend them more credit for goods when annuity payments were late, the traders refused. Myrick wrote a letter to his brothers about the incident:

"A.J. Myrick to Dear Brothers July 26, 1862, OIA Special File 271.

[Lower] Sioux Agency July 26th [18]62

Dear Brothers —

The Lower Indians have been playing the devil in general. They had two secret councils at which they resolved not to pay a dollar of their credits, established a soldiers lodge of one hundred warriors to execute the plan.... we all determined not [to] give any more credit hoping to starve them into a change of sentiment....

[Yesterday] they formed a line of battle marched to all the stores and made the following… speech “You have said you have closed your stores for 2 Sundays and that we should have to eat grass. We warn you not to cut another stick of wood or to cut our grass,” feeling themselves probably much relieved departed ... In their secret council there [were] some intimations that the present traders were to be driven off and someone new to have exclusive control of the trade. Now whether the agent had anything to do with it we can’t find out but it looks very much as if that was the programme.

I am at a loss and so doing have given out no credits since last Sunday and at present deem it best not to give away any more for a week or ten days hoping it will produce a reaction. They will get very hungry and possibly if the officials are not engaged in it they may change their sentiments and favor paying their credits ...

I wish you could come up and suggest to Forbes to come and help straighten out the snarl the Indians have got us in. I have not talked with them yet seeming it best to let them get hungry first hoping they might retract and become decent again."

On August 18, at the start of the U.S.-Dakota War, Myrick was killed while trying to run away from the Lower Agency, one of the first whites to die. Stories say he was found with grass stuffed in his mouth.

Wakute

>Wakute (Wacouta) was a Mdewakanton chief who opposed the war. He was imprisoned in the aftermath at Fort Snelling and then Mankato.

View full article: Wakute

Makato

Born about 1822, Mankato was the son of Good Road, for whose family the village "Mankato" was named. The Blue Earth River takes its name from the Dakota phrase "Makato Osa Watapa," or "the river where blue earth is gathered."

Mankato was a member of the delegation who signed the Treaty with the Dakota on June 19, 1858. He appears (left) in the famous photograph of the treaty signers made at a photography studio in Washington, D.C. During the U.S.-Dakota War he led a band of Mdewakanton soldiers into battle at Fort Ridgely, Birch Coulee, and Wood Lake. On September 23, 1862, he was killed by a cannonball at the battle of Wood Lake.

Taoyateduta (Little Crow)

"We have waited a long time. The money is ours, but we cannot get it. We have no food, but here are these stores, filled with food. We ask that you, the agent, make some arrangement by which we can get food from the stores, or else we may take our own way to keep ourselves from starving. When men are hungry they help themselves"

Taoyateduta, 1862

Taoyateduta (which translates as "His Scarlet Nation," though he was more often known as Little Crow, after his father) was born into the Mdewakanton village of Kaposia about 1810. He succeeded his father as leader in 1846. During the 1850s, he was widely recognized as a spokesperson for all the Lower bands of Dakota. He was a negotiator and signer of the Treaty of Mendota in 1851 and the Treaty of 1858. By the 1860s, Little Crow had adopted some European customs — he owned some European-styled clothing, for example, and he lived in a wood-frame house. But like most Dakota farmers on the Lower reservation, he staunchly refused to compromise his Dakota religious beliefs.

Little Crow tried to use his knowledge of white culture to guide the course of the war. On August 19, with hundreds of settlers already dead in Brown and Renville counties, and with attacks on white settlements continuing, he is reported to have said, "Soldiers and young men, you ought not to kill women and children. . . . You should have killed only those who have been robbing us so long. Hereafter make war after the manner of white men."

On September 7, 1862 — three weeks into the fighting — Little Crow sent a letter to Henry Sibley pinpointing the reasons Lower soldiers went to war. Little Crow’s letter condenses decades of frustration over misuse of government funds, late annuity payments, and poor relations between government officials and Dakota leaders into a few terse sentences.

"Dear Sir – For what reason we have commenced this war I will tell you. it is on account of Maj. Galbrait [sic] we made a treaty with the Government a big for what little we do get and then cant get it till our children was dieing with hunger – it is with the traders that commence Mr A[ndrew] J Myrick told the Indians that they would eat grass or their own dung. Then Mr [William] Forbes told the lower Sioux that [they] were not men [,] then [Louis] Robert he was working with his friends how to defraud us of our money, if the young braves have push the white men I have done this myself."

Letter to Col. Sibley, Sept. 12, 1862:

"Red Iron Village or Mazawakan

To Hon H. H. Sibley

We have in Mdewakanton band one hundred & fifty five prisoners. not including the Sisiton [sic] & Warpeton [sic] prisoners. then we are waiting for the Sisiton what we are going to do with the prisoners they are coming down. they are at Lake qui Parl now. the words that I have sent to the governed I want to here [sic.] from him also. and I want to know from you as a friend what way that I can make peace for my people. in regard to prisoners they fair [sic.] with our children or our self just as well as us

your truly friend

Little Crow

per Scott Campbell"

After the Battle of Wood Lake, he left Minnesota and attempted to gather support for a continued war in the west and Canada. He was killed on July 3, 1863 after returning to Minnesota. For many years some of his remains were put on display by the Minnesota Historical Society before being returned to his descendants for burial.

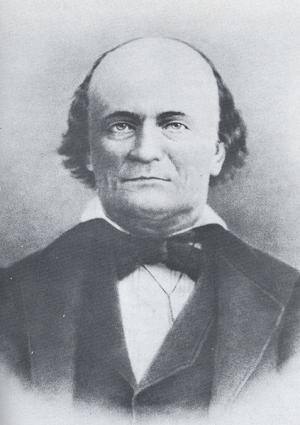

Henry H. Sibley

In 1834, Henry Sibley became a partner in the American Fur Company and settled in Mendota, Minnesota. Like a number of other traders, Sibley entered into a relationship with a Dakota woman, Red Blanket Woman. Their relationship produced a daughter, Helen Sibley, before the couple parted to live separate lives. Sibley acknowledged his daughter, protected her interests and education, and remained involved in her life. After the fur trade dwindled, Henry Sibley became a successful businessman, investing in lumbering, river transportation, railroads, and land. He played a pivotal role in the 1851 treaty negotiations and later commanded U.S. troops during the war and on the 1863 punitive expeditions. From 1867-70, he served as president of the Minnesota Historical Society.

During the war, Sibley was vilified in the press for his slowness in advancing to Fort Ridgely to liberate captive settlers. He wrote to his wife on September 4, 1862:

"I see . . . that the people are dissatisfied with my slow advance. Well, let them come and fight these Indians themselves, and they will [have] something to do besides grumbling. I have told Gov. R. in my dispatch that he can have my commission when he sees fit, as I would be too glad to let some one take my place. . . . I have not slept more than an hour in two nights, and have been in the saddle almost [all] of the time for two days and nights. . . ."

Colonel Sibley to Governor Ramsey, August 25, 1862:

"My heart is steeled against them, and if i have the means, and can catch them, I will sweep them with the besom of death."

Sibley convened the military commission that condemned 303 Dakota men to death in the wake of the war.

Letter From Col. Henry Sibley to the Assistant Secretary of the Interior, December 19th, 1862.

"[I]t should be borne in mind that the Military Commission appointed by me were instructed only to satisfy themselves of the voluntary participation of the individual on trial, in the murders or massacres committed, either by voluntary participation of the individual on trial, in the murders or massacres committed, either by his voluntary concession or by other evidence and then to proceed no further. The degree of guilt was not one of the objects to be attained, and indeed it would have been impossible to devote as much time in eliciting details in each of so many hundred cases, as would have been required while the expedition was in the field. Every man who was condemned was sufficiently proven to be a voluntary participant, and no doubt exists in my mind that at least seven-eighths of those sentenced to be hung have been guilty of the most flagrant outrages and many of them concerned in the violation of white women and the murder of children."

Source: Executive documents, MNHS collections and Henry H. Sibley: An Inventory of His Papers at the Minnesota Historical Society and Governors of Minnesota.

Wabaṡa

"We think our Great Father may have forgotten his Red children & our hearts are very heavy — the Agents he send to us seem to forget their father’s words before they reach here for we often think they disobey what he has said. . . . You have said you are sorry to see my young men engaged still in their foolish dances--it is because their hearts are sick. They don’t know that whether these lands are to be their home or not."

Wabaṡa to Bishop Whipple, 1862

Chief Wabaṡa (also known as Wabasha, Wapasha, or Tahtapesaah), a member of the Mdewakanton band of Dakota, lived on a farm on the Lower Reservation by the Agency. During the U.S.-Dakota War, there were divisions between groups of Dakota people who were for or against the fighting. Wabaṡa joined a group of Dakota called the Peace Party whose aim was to bring people to safety.

After the war, Wabaṡa was exiled to Crow Creek in South Dakota, and later to Santee, Nebraska.

Alexander Ramsey

"Our course then is plain. The Sioux Indians of Minnesota must be exterminated or driven forever beyond the borders of Minnesota."

Alexander Ramsey to a special session of the Minnesota legislature, September 9, 1862

Alexander Ramsey was born September 8, 1815, at Hummelstown, Pennsylvania.

In 1849, Ramsey was appointed governor of Minnesota Territory by President Zachary Taylor. In this role, he also acted as the territory’s Indian superintendent. Aware that his political future depended on his ability to open lands west of the Mississippi River for white settlement, Ramsey teamed up with his friend Henry Sibley, a former fur trader who was also the territory's delegate to the U.S. Congress. Together with Luke Lea, U.S. Commissioner of Indian Affairs, they negotiated the treaties of 1851. Ramsey was investigated and acquitted by the U.S. Congress on allegations of fraud connected to the 1851 treaty negotiations.

During his political career, Ramsey held many offices in Minnesota and Washington, D.C.: territorial governor, mayor of St. Paul, state governor, U.S. senator, and Secretary of War under President Rutherford B. Hayes. He was also a shrewd businessman, and made a sizeable fortune in real estate. Ramsey was also the first president of the Minnesota Historical Society, a post he was holding when the U.S.-Dakota War broke out in 1862.

Wambditanka (Big Eagle)

"There was great dissatisfaction among the Indians over many things the whites did. The whites would not let them go to war against their enemies. . . . Then the whites were always trying to make the Indians give up their life and live like white men--go to farming, work hard as they did--and the Indians did not know how to do that, and did not want to anyway. It seemed too sudden to make such a change. If the Indians had tried to make the whites live like them, the whites would have resisted, and it was the same way with many Indians. The Indians wanted to live as they did before the treaty of Traverse des Sioux--go where they pleased and when they pleased, hunt game wherever they could find it, sell their furs to the traders and live as they could."

Wambditanka (Big Eagle), Mdewakanton Dakota leader, in an interview conducted with journalist Return I. Holcombe in 1894

Also known as Jerome Big Eagle, Wambditanka was born in 1827 at Black Dog’s village, a few miles above Mendota on the south bank of the Minnesota River. He succeeded his father, Grey Iron, as chief in 1857. By 1858 had moved to the Redwood (Lower Sioux) Agency to farm. When war broke out he joined the fighting and was at the battles of New Ulm, Fort Ridgely, Birch Coulee, and Wood Lake. After the war he was tried and convicted by the military commission, but received a pardon from President Lincoln in 1864. After several years living on reservations, Wambditanka and his family returned to Minnesota where he lived until 1906.

On the war of 1862:

"It began to be whispered about that now would be a good time to go to war with the whites and get back the lands. It was believed that the men who had enlisted [to fight in the Civil War] last had all left the state, and that before help could be sent the Indians could clean out the country, and that the Winnebagoes [Ho-Chunk], and even the Chippewas [Ojibwe], would assist the Sioux. It was also thought that a war with the whites would cause the Sioux to forget the troubles among themselves and enable many of them to pay off some old scores. Though I took part in the war, I was against it. I knew there was no good cause for it, and I had been to Washington and knew the power of the whites and that they would finally conquer us. We might succeed for a time, but we would be overpowered and defeated at last. I said all this and many more things to my people, but many of my own bands were against me, and some of the other chiefs put words in their mouths to say to me."

"I did not have a very large band. . . . Most of them were not for the war at first, but nearly all got into it at last. A great many members of the other bands were like my men; they took no part in the first movements, but afterwards did. . . . When I returned to my village that day I found that many of my band had changed their minds about the war, and wanted to go into it. . . . I was still of the belief that it was not best, but I thought I must go with my band and my nation, and I said to my men that I would lead them into the war, and we would all act like brave Dakotas and do the best we could. All my men were with me; none had gone off on raids, but we did not have guns for all at first."

Anpetutokeca (John Other Day)

"When I gave up the war path and commenced working the earth for a living I discarded all my former habits.... My wife died during the winter which left my heart very sad. It was very hard for me to learn the white man’s ways, but I was determined to get my living by cultivating the land and raising stock."

Anpetutokeca (John Other Day), 1869

Anpetutokeca, also known as John Other Day, was born in about 1819 in present-day Nicollet County. He was a leader of a small band of Wahpeton Dakota farmers living on the reservation near the Upper Agency with his wife, Roseanne. For rescuing more than 60 residents of the Upper Agency, Other Day was received as a hero in St. Paul. He served as a scout for Henry Sibley and fought beside white soldiers at the battle of Wood Lake. He died in Dakota Territory in 1869.

Jacob Nix

Jacob Nix was an immigrant from Bingen on the Rhine, Germany.

When the revolution of the German states broke out in 1848, Nix joined the struggle and became a captain in the “Free Corps.” Sentenced to death for treason, Nix escaped to the United States and in 1858 settled in New Ulm and opened a general store.

Due to his previous military experience, Nix was appointed commander of the New Ulm forces when the Dakota War broke out. He successfully defended the town during the first onslaught. After the war, Nix joined the Union army and participated in punitive expeditions.

From The Sioux Uprising in Minnesota, 1862 : Jacob Nix's Eyewitness History:

"One should not, of course, have provoked the Indians with injustices, but they also should not have made the inhabitants of an entire region pay for the wrongs committed by specific individuals by murdering, burning, and scorching the earth, and attacking settlers, destroying everything -- men and women, old people and children -- which came before their rifles and bows and arrows. Then, of course, there suddenly appeared the fanatics who immediately took up the cause of the captured red murderers after the defeat of the uprising. The following momentous words from the Bible should have been cast before these crazy, hypocritical puritans: An eye for an eye! A tooth for a tooth! That means: Immediately after the capture of the red scoundrels, one should not have wasted any time in shooting or hanging every one who took part in the horrible crimes which occurred in the summer of 1862 in Minnesota."

Contemporary Comment:

"If it wasn’t for Captain Nix, I wouldn’t be alive today, because Grandma refused to leave the farm. . . . He heard about the Uprising occurring, and that it got to New Ulm. So he came back and dragged her out of the house. She wouldn’t go. He said: ‘You can stay here, but I’m taking the kids.’ She finally went along with it, reluctantly."

Richard Runck, oral history, New Ulm, 2011

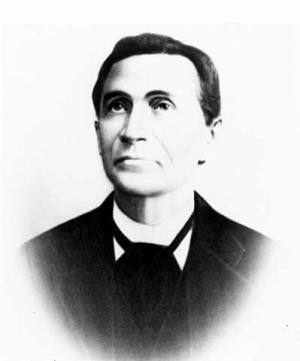

Thomas Williamson

Thomas Williamson was a medical doctor who arrived in Minnesota in 1835. Along with caring for a multitude of Dakota and white patients, he, along with John Renville, Stephen Riggs and Gideon and Samuel Pond, helped create the first written alphabet and grammar of the Dakota language. Thomas Williamson established a mission at Lac qui Parle in 1835.

He was at Pejuhutazizi (Yellow Medicine), his mission near the Upper Agency, when he received word of the war on August 18, 1862. Rather than fleeing immediately he stayed and supported the many Dakota men who, at great risk to their families, chose not to fight. Williamson; his wife, Margaret; and his sister, known as “Aunt Jane” Williamson, were finally convinced to leave on August 20. “Christian Indians had staid by us all night guarding us while we slept and assisting us when awake in every way in their power,” Williamson wrote. Two Christian Dakota men provided the Williamsons with a team of oxen and a wagon to use during their escape: Robert Hopkins Caske, a neighbor; and Simon Anawaƞgmani, who headed a Wahpeton band living near Stephen Riggs’s Hazelwood Mission. Peace Party members Lorenzo Towaƞiteton Lawrence, Little Paul Mazakutemani, Peter Tapataṭaƞka (Big Fire), and Enos Maḣpiyahdinape were also involved in this dangerous enterprise.

Williamson escaped to St. Peter, where he helped care for wounded war victims. He later ministered to Dakota men imprisoned at Mankato and at Camp McClellan in Davenport, Iowa. Williamson convinced President Lincoln to pardon 25 Dakota men in April 1864; after Lincoln’s death in 1865 he advocated for the remaining prisoners with Pres. Andrew Johnson. In 1866, Johnson pardoned the remaining prisoners, still at Camp McClellan. Thomas Williamson died at St. Peter in 1879.

Letter From Thomas Williamson to Stephen Riggs on November 24, 1862:

"[I] am satisfied in my own mind from the slight evidence on which these are condemned that there are many others in that prison house who ought not to be there, and that the honor of our Government and the welfare of the people of Minnesota as well as that of the Indians requires a new trial before unprejudiced judges. I doubt whether the whole state of Minnesota can furnish 12 men competent to sit as jurors in their trial. . . . From our Governor down to the lowest rabble there is a general belief that all the prisoners are guilty, and demand that whether guilty or not they be put to death as a sacrifice to the souls of our murdered fellow citizens."

Thomas J. Galbraith

"For what reason we have commenced this war I will tell you. It is on account of Major Galbraith."

Little Crow in a letter to Henry Sibley, 1862.

Thomas J. Galbraith was an American politician. In 1857, he signed the Republican version of the Minnesota State Constitution. In the wake of Lincoln’s election in November 1860, Republicans swept the federal jobs in the Northern Superintendency of Indian Affairs and the thirty-six-year-old Galbraith was appointed Sioux Agent. As an agent appointed by the U.S. government, he was charged with fulfilling treaty obligations to the Dakota and with enforcing Indian affairs code, including regulating the traders.

By the spring of 1862, fed up with the inefficiencies of the Indian system in which he was enmeshed, Galbraith resigned his post as Agent, then agreed to hold his resignation until after the annuity payment was made. Throughout the summer he tried to deal with an impossible situation. When annuity payments were delayed, he tried to convince the Dakota to accept greenbacks rather than the gold promised them. He kept the few government rations he had left locked in a warehouse at the Lower Agency and he tried to convince traders to extend more credit to Dakota clients for much-needed food.

On August 18, Galbraith and a group of Civil War recruits known as the Renville Rangers took off from the Upper Agency. Galbraith believed he would deliver the recruits to Fort Snelling, return to the reservation to make the annuity payment, then accept a leadership position in a Minnesota regiment as thanks for his recruiting efforts.

News of the outbreak of war overtook Galbraith and his recruits at St. Peter on August 19. The Renville Rangers changed course and marched to the aid of Fort Ridgely. Meanwhile, Galbraith’s wife, Henrietta, and their two children were being led to safety from their home at the Upper Agency by the Wahpeton Dakota leader Anpetutokeca (John Other Day). Galbraith helped defend Fort Ridgely and was wounded at the battle of Birch Coulee. After the war Galbraith was exonerated in two congressional investigations into allegations that his conduct at the Agency brought on the U.S.-Dakota War. Galbraith died in Cheyenne, Wyoming, in 1909.

Related Images

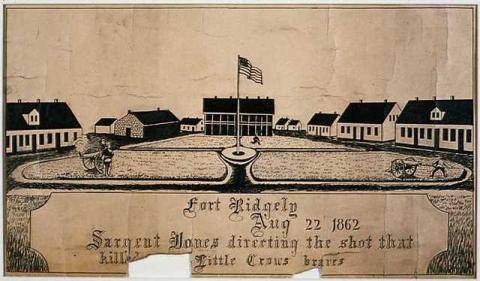

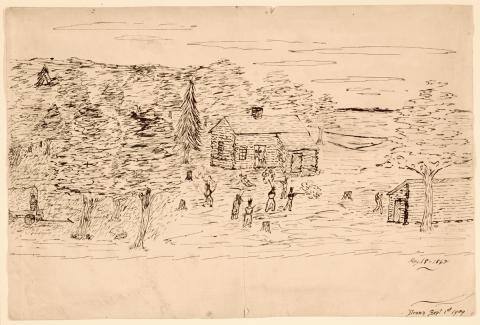

Fort Ridgely Drawing

A drawing of Fort Ridgely in 1862, by anonymous.

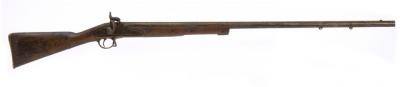

Musket

This musket was used by Captain Louis Buggert who led a Brown County militia unit and was killed in the second battle of New Ulm on August 23rd, 1862.

Dakota Attacking Camp

Reproduction of an original drawing, artist unknown.

Mirrored Chest of Drawers

Dark stained wood dresser with three full-width drawers. Chest of drawers was reportedly used as a hiding place for a settler's infant in New Ulm, Minnesota, during the 1862 U.S.-Dakota War

Scene of the Acton Murders, August 18, 1862

An interpretation of the shootout that occurred in Acton, MN, on August 17th, the day before the start of the U.S.-Dakota War. By Dan Nelson, 1909.

New Ulm Attack

Anton Gag, 1904

The Attacks on New Ulm

On the afternoon of August 19, 1862, New Ulm came under siege by a relatively small group of Dakota warriors. This skirmish lasted several hours and left five settlers dead. The following day the people of New Ulm elected Judge Charles Flandrau, a prominent citizen from St. Peter, as their military commander. Over the next few days more than 1,000 refugees ballooned New Ulm’s population to 2,000 people, while only 300 were equipped to fight. The second battle of New Ulm took place on August 23. This time, however, more than 600 Dakota soldiers fought, under the guidance of Chiefs Waƞbdiṭanka, Wabaṡa, and Makato. After holding off the attack, Charles Flandrau led the evacuation of New Ulm on August 25, leaving much of the city in ashes.

Louis Buggert, who led a Brown County militia unit, was killed

in the second battle of New Ulm on August 23. This was his musket.

Missionary Party, August 21, 1862

Missionary party, August 21, 1862

Photograph by Adrian Ebell

On August 19, a group of about 35 missionaries, mission workers, and government employees fled from the Upper Agency. They headed first toward Hutchinson, then rerouted toward Fort Ridgely.

Adrian Ebell escaped with this party, and took their photo during a breakfast break. It is the only extant photo taken during the war.

Richard Orr was injured when Dakota attacked his trading post at Big Stone Lake and killed his partner. Stephen Riggs wrote that “our wagons were more than full, but we could make room for a wounded white man.” When the party reached safety, Orr went to St. Peter, where he was hospitalized for two months.

Mr. and Mrs. D. Wilson Moore were visiting Minnesota on their honeymoon and had come to the Upper Agency to observe the process of annuity payments. After reaching safety, the Moores took a steamboat to St. Paul, then returned home to New Jersey.

Stephen Riggs was a longtime missionary to the Dakota. His wife, Mary, and their children Cornelia, Isabella, Robert, Thomas, Henry, Anna, and Martha are also in the photograph.

Sophia Robertson was the daughter of Andrew Robertson and his wife, Jane, the granddaughter of Grey Cloud, and the great-granddaughter of Wabasha.

Elizabeth (Williamson) and Andrew Hunter: Elizabeth was the daughter of Dr. Thomas Williamson.

Hugh and Mary Cunningham were houseparents for the boarding school at Stephen Riggs’s Hazelwood mission. Hugh’s sister Martha was also with the party.

Henry and Nancy Williamson were the children of Dr. Thomas and Margaret Williamson.

Jonas Pettijohn, a former teacher in the government school at Red Iron’s village (12 miles northwest of Riggs’s mission), was moving his family to St. Peter when war broke out. His wife, Fanny, and children Alice and William were also with the party.

Battle of Birch Coulee

Dorothea Paul, about 1975

Birch Coulee: September 2

On September 2, 1862, a burial party of 170 men under the command of Maj. Joseph R. Brown was camped at Birch Coulee when they were surrounded and attacked by a group of 200 Dakota soldiers. Over the next 30 hours Brown’s forces lost 13 men and 90 horses, and more than 50 men were injured. There were two recorded Dakota deaths. The fighting finally ended on the morning of September 3rd, when Henry Sibley arrived with reinforcements and artillery.

This "Mississippi rifle" was used during the battle of Birch Coulee during which it was disabled by a bullet strike to its barrel.

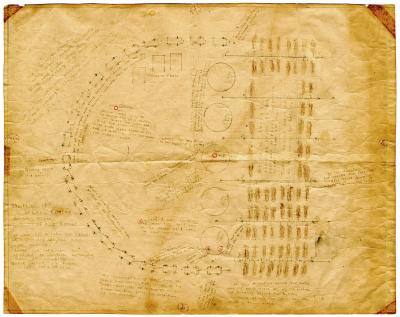

Robert Knowles Boyd, Battle of Birch Coulee: Ground Plan of the Corral, about 1926

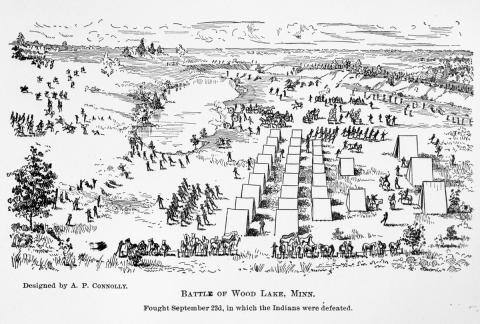

Wood Lake

From: A thrilling narrative of the Minnesota massacre and the Sioux War of 1862-63 / A.P. Connolly. Chicago, c1896.

Wood Lake: September 23

On the morning of September 23, Henry Sibley and his forces were camped near the shore of Lone Tree Lake. Before dawn, Dakota soldiers had hidden in the grass waiting to ambush Sibley’s forces as they broke camp and marched down the road. But before they could carry out this plan, several foraging soldiers from the Third Minnesota began crossing the prairie in the direction of the Dakota. When the US soldiers were nearly upon them, the Dakota opened fire and the battle began. The veterans of the Third Minnesota and Sibley’s militia forces eventually drove the Dakota from the field. Over the course of this battle seven white soldiers were killed and 33 were wounded. Fifteen Dakota, including chiefs Makato and Mazamani, were killed during or after this battle, which effectively ended organized Dakota war efforts in Minnesota.

Six Weeks of War: August 18 to September 26, 1862

Map by Philip Schwartzberg, courtesy Pond Dakota Heritage Society; annotations adapted from “The Dakota Conflict--A Brief Chronology,” Minnesota’s Heritage, vol. 1 (January 2010).

Milford Township

Milford Township

Located just west of New Ulm in Brown County, Milford Township was populated by mostly German immigrants. It was attacked on August 18, 1862. More than 50 Milford Township residents were killed, making it one of the hardest-hit communities during the war. In 1862

This monument, erected in about 1930, commemorates those killed.

Maximilian and Lucretia Zeller were living in Milford Township with their six children: John, Monika, Barbara, Caezilia, Conrad, and John Martin. During the August 18 attack, the entire Zeller family, with the exception of 14-year-old John, was killed. Following the war John moved to Columbus, Ohio, where he died in 1867.

John Zeller, aged 19 yrs, committed suicide last Friday. He was of German parentage and had been working for George Ferguson since last August. His father having emigrated to this country ten years ago and settled in Minnesota. At the terrible massacre of settlers by the Indians of that state at New Uhlm (sic), about 5 yrs ago, young Zeller’s parents and 5 of his brothers and sisters were killed by the Indians. He alone of the family escaped. -Delaware Gazette, April 19, 1867

Related Documents

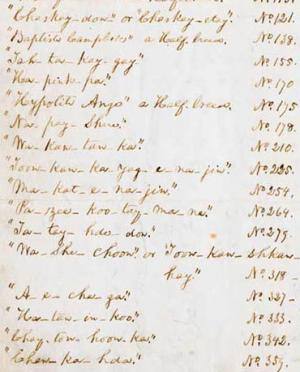

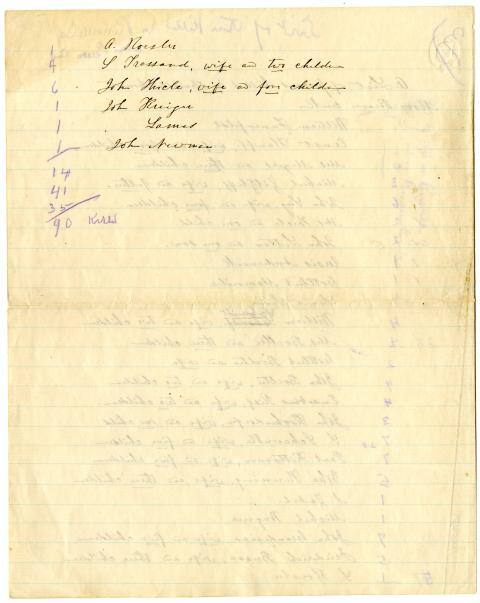

List of Whites Killed in Renville County

"List of whites killed in Renville County," 1862.

Stephen Riggs likely made this list while interviewing freed captives at Camp Release, after the war ended and before trials of Dakota men began.

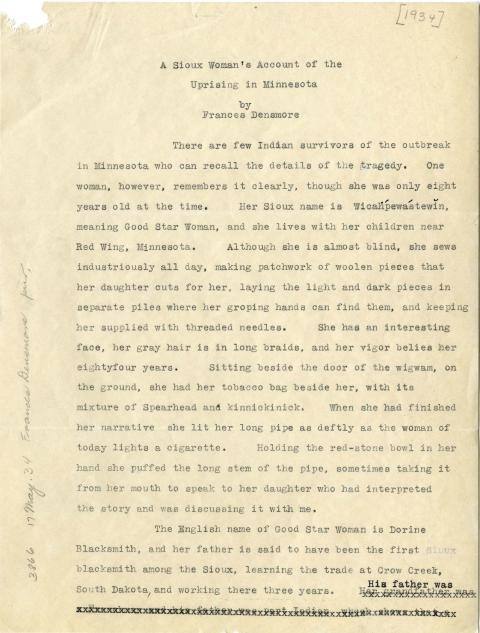

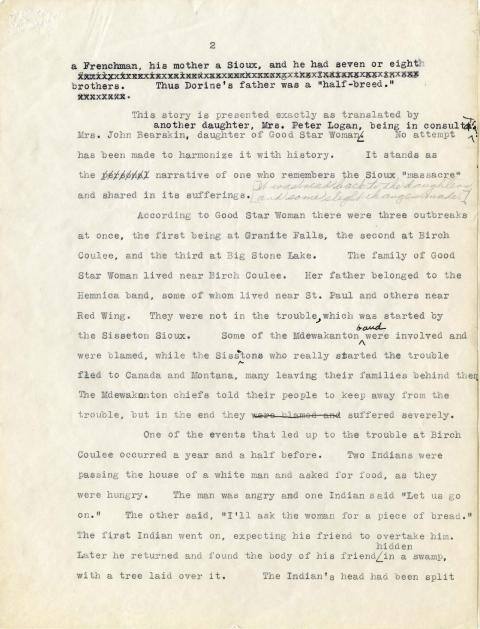

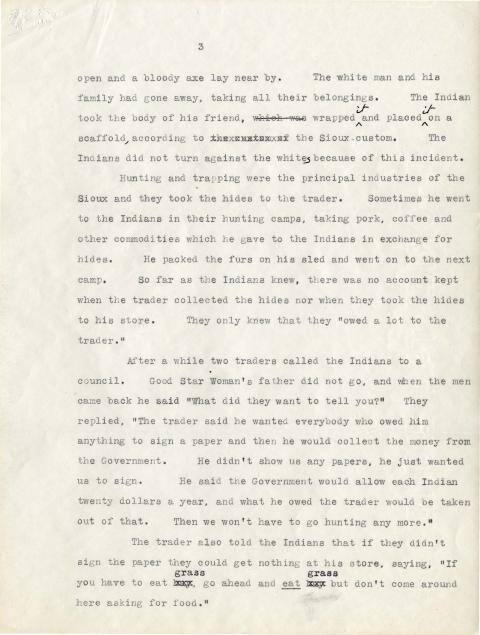

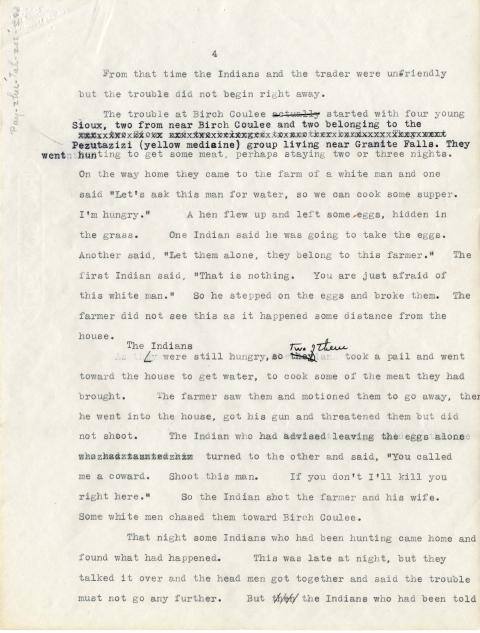

Wicahpewastewin Account

Written by ethnologist Frances Densmore in 1934, this account of the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862 draws upon the memories of Good Star Woman (Wicahpewastewin or Wicanhpiwastewin), a Mdewakanton Dakota woman who was eight years old during the conflict. The account includes background to the conflict, recollections of time spent in the internment camp at Fort Snelling after the war, and the removal of the Dakota people from Minnesota.