Land & Lifeways

"Whenever, the course of a daily hunt, the hunter comes upon a scene that is strikingly beautiful, or sublime; a black thundercloud with the rainbow's glowing arch above the mountain, a white waterfall in the heart of a green gorge, a vast prairie tinged with the bood-red of the sunset; he pauses for an instant in the attitude of worship. He sees no need for setting apart one day in seven as a holy day, because to him all the days are God's days."

"Whenever, the course of a daily hunt, the hunter comes upon a scene that is strikingly beautiful, or sublime; a black thundercloud with the rainbow's glowing arch above the mountain, a white waterfall in the heart of a green gorge, a vast prairie tinged with the bood-red of the sunset; he pauses for an instant in the attitude of worship. He sees no need for setting apart one day in seven as a holy day, because to him all the days are God's days."

Ohiyesa (Dr. Charles Eastman), from The Soul of the Indian, 1911.

According to many, the area now known as Minnesota has been called "home" by Dakota people for thousands of years. For hundreds of years the Santee (or Eastern) Dakota moved their villages and varied their work according to the seasons. They spent the winter living off the stores of supplies built up during the previous year. Women gathered wood, processed hides, and made clothes while men hunted and fished. In the spring, villages dispersed and men left on hunting parties, while women, children, and the elderly moved into sugaring camps to make maple sugar and syrup. During the summer months families gathered in villages and men hunted and fished while women and children cultivated crops such as corn, squash, and beans. Once the corn had been harvested, families focused on gathering wild rice along the rivers. In autumn, families moved to the year's chosen hunting grounds for the annual hunt. This traditional lifestyle of communal support was the basis for Dakota society and culture.

Read more about Dakota values in Beginning Dakota/Tokaheya Dakota Iyapi Kin and Dakota connection to the land at the Bdote Memory Map.

Theme:

Dakota HistoryTopics:

Dakota LandPermissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at Copyright and Use Information.

Bibliography

Anderson, Gary Clayton. Kinsmen of Another Kind: Dakota-White Relations in the Upper Mississippi Valley, 1650-1862. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1997.

Deloria, Ella. The Dakota Way of Life. Sioux Falls, SD: Mariah Press, 2007.

Deloria, Ella. Speaking of Indians. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1998.

Eastman, Charles Alexander. The Soul of the Indian. Houghton Mifflin: Boston & New York, 1911.

Gibbon, Guy. The Sioux: The Dakota and Lakota Nations. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2003.

Oneroad, Amos E., and Alanson B. Skinner. Being Dakota: Tales and Traditions of the Sisseton and Wahpeton. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2003.

Spector, Janet D. What This Awl Means: Feminist Archeology at a Wahpeton Dakota Village. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1993.

Waziyatawin. Remember This!: Dakota Decolonization and the Eli Taylor Narratives. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2005.

Waziyatawin. What Does Justice Look Like? The Struggle for Liberation in Dakota Homeland. St. Paul, MN: Living Justice Press, 2008.

Resources for Further Research

Websites

Primary

Key People

Ohiyesa (Charles Eastman)

Author Molly Huber

Famed author and lecturer Charles Eastman was raised in a traditional Dakota manner until age fifteen, when he entered Euro-American culture at his father's request. He spent the rest of his life moving between American Indian and white American worlds, achieving renown but never financial security.

The boy later known as Charles Alexander Eastman was born on February 19, 1858, near Redwood Falls, Minnesota. His mother, Wakantankawin (Sacred Woman) or Mary Nancy Eastman, daughter of well-known painter Seth Eastman, only survived her son's birth by a few months, so he was called Hakadah (the Pitiful Last). His paternal grandmother, Uncheedah, raised him, first in Minnesota and then, after the US–Dakota War of 1862, in Canada where his family had fled to safety.

In Canada, Hakadah was renamed Ohiyesa (the Winner) following a victory by his band in a lacrosse game. He was instructed in traditional Dakota lifeways by his grandmother and uncle, Mysterious Medicine. Ohiyesa's father, Ite Wakanhdi (Many Lightnings), and older brothers were thought killed in the aftermath of the US–Dakota War. However, they had survived, and in 1873, Ite Wakanhdi, then called Jacob Eastman, traveled north to find his youngest son and bring him back to the United States.

Ohiyesa was shocked by his father's sudden reappearance and request that he give up traditional Dakota ways. But Ohiyesa agreed to follow his father to his homestead in Flandreau, Dakota Territory, and adopt white ways, taking the name Charles Alexander Eastman.

In Flandreau, Eastman started formal schooling, which he continued at various institutions for the next seventeen years. He moved from Indian schools such as Santee Normal in Nebraska to all-white colleges such as Beloit and Dartmouth. He completed his education in 1890 with a medical degree from Boston Medical School.

Eastman wanted to give back to his community as a reservation physician, so he applied to the Bureau of Indian Affairs and received an appointment to Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota. At Pine Ridge, he met Elaine Goodale, a teacher and published author, and they were married in 1891.

Eastman arrived at Pine Ridge in November 1890, just before the tragic events at Wounded Knee on December 29. As the reservation's resident physician, he provided medical assistance to the day's few survivors and found his confidence in white culture severely shaken. Eastman's time at Pine Ridge was troubled overall and lasted only until 1893, when he left because of conflict with the Indian agent.

Eastman and his wife then moved to St. Paul, where he attempted to set up a private medical practice. Unsuccessful, he took a job with the YMCA as supervisor of their Indian programs in the western United States and Canada.

He tried reservation medical practice again in 1900, at Crow Creek Reservation, but resigned after only two years due to conflict with his supervisors. In 1903 he was offered another job within the Indian service: to assist Dakota in establishing family names that would translate well into English and could be used legally. He continued this work for six years.

In 1902, Eastman became a published author. His first book, Indian Boyhood, is a compilation of stories he had been telling his own children about his childhood. The book was immediately popular. Encouraged by its success, Eastman continued to write for children and adults. He published thirteen books in all, two co-written with his wife, who served as his editor.

Largely because of his publishing success, Eastman became a noted speaker and traveled widely. In 1910, he took a job with the Boy Scouts of America as their Indian advisor. Inspired by this experience, he opened a summer camp for children in New Hampshire that he and his family ran from 1915 to 1921.

In 1921, Eastman and his wife permanently separated after many unhappy years together and never saw each other again. During the remaining eighteen years of his life, Eastman continued to lecture but no longer published. He increasingly withdrew from white society, building himself a small cabin in the woods of upstate New York, where he spent most of his time. He died of heart failure in 1939 while visiting his son, Ohiyesa II, in Detroit, Michigan.

Related Images

Dakota Encampment

A Yankton Village

Santee Man

Sioux Women

Santee Dakota women about 1870.

When looking at photography of American Indian and other indigenous peoples, it is important to remember that Euro-Americans often set out in the early era of photography to capture their ideas of Indian peoples. The photographs are often misrepresentations, showing Indians wearing European clothing or engaging in white lifeways. This was a reflection of the pressure for Indians to assimilate to white ways at the time. Alternately, photographers posed their Indian subjects in a way that they thought represented what Indian people were and often were exaggerations and/or racist interpretations.

Read more about how Native Americans are represented in media: Examples of these photographic representations are:

Schupman, Edwin. Photography changes the ways cultural groups are represented and perceived. Smithsonian Photography Initiative.

Examples of these photographic representations are:

Pictures of Native Americans in the United States. The National Archives.

Traveling

This painting by Seth Eastman in 1869 is an interpretation of Dakota traveling using a travois (trah-voy). Courtesy of Architect of the Capitol.

In order to live close to food resources such as maple forests or ricing lakes, the Dakota had to pack and move their whole household. Since Dakota women owned the tipis and everything in them, packing and moving was usually women's work. Moving camp was hard, especially during the winter. Starting at daybreak, women and children packed and carried heavy bundles through snow and icy water, if the streams were not frozen.

In the early 1800s, Samuel Pond, a missionary who traveled with the Dakota said:

"Fourteen teepee poles were to be found and dragged often a considerable distance through the snow making two or three heavy loads for a strong woman. The tent was then erected, and dry grass cut up from some swamp was brought and put all around the tent or teepee on the outside, for the Indian women would not bank their tents with snow lest is should melt and injure the tent. Hay was also strewn inside to spread the beds on, for the frozen ground was hard and cold. Then wood was brought for the fire, very dry for they burn no other. Las of all water was brought and hung over the fire to warm or cook supper, which by this time was well earned if ever suppers are."

To here a contemporary perspective on traditional Dakota womens' work, click here.

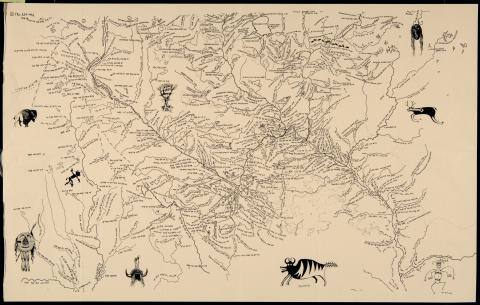

Where the Water Gather Map

Paul Durand (1917-2007), who created this map, wrote, “The greater part of these place names has been gleaned from the field-notes and maps of Joseph Nicollet, commissioned in the 1830s by the US government to survey the Upper Missouri and Mississippi River basins.” It is a map of Dakota names for sites in the area that is current-day Minnesota.

About this map, Reverend Gary Cavender wrote:

“The writing of history, that which gets recorded, is almost always presented from the viewpoint of the dominant culture of the time. This is what occurred when the first Europeans arrived on the continent or the “New World” as it was called by them... It certainly wasn’t new to the ones who lived here; rather, it was an ancient and familiar place, a world with myths and beginnings and cycles --reasons why life is lived in a certain way. There were names of places that told what happened here, that described the center of the earth, or the war of the sky god and the god of the nether regions. Yes, this was certainly an old and active world. That was soon to change, however; the newcomers would change all that. They would put their names on these places. Their heroes would now identify these places and the ancient names would fade, soon to be forgotten. Where the Rivers Gather and the Waters Meet will not allow that to happen....It will preserve the past before American history began. Future generations will know there was a time before American history.”

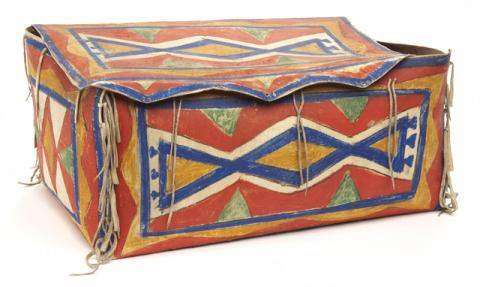

Parfleche Container

The Dakota made containers, like this box called a parfleche (Pahr-flesh). These containers were made of bison (buffalo), elk, or moose rawhide into various shapes. This parfleche case was made from a single price of leather in 1911. It was owned by the Lakota chief Red Fox.

Carved bone hide scraper, MNHS collections.

Dakota Shirt

Dakota man's painted hide shirt, 1870-80

Dakota woman's wool and hide dress,1850-60.

Mocassins, about 1900.

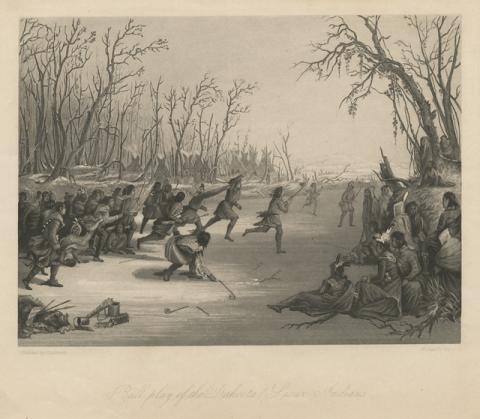

Dakota Ball Game

This painting by Seth Eastman was done in 1850 and was later engraved by Isacc E Burt. It shows Dakota playing a ball game. To play, competitors threw a ball between them, catching it with a stick that had a small basket on the end, like today's game of lacrosse. Lacrosse was invented by eastern American Indian nations. For more information see North American Indigenous Games.

Dakota Village

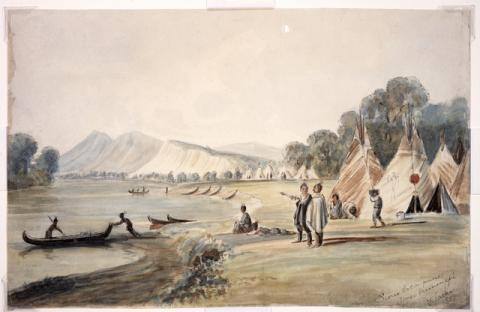

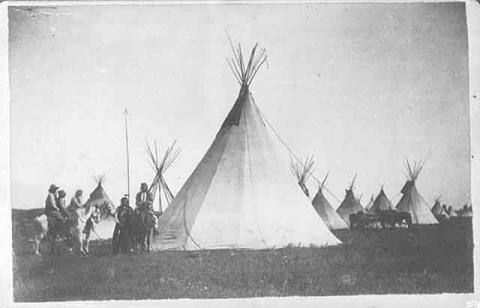

An interpretation of a Dakota village on the Mississippi, near Fort Snelling in Minnesota by Seth Eastman, 1846-48. Historically, Dakota lived in tipis or bark houses. Tipis were cone-shaped houses made by stretching animal skins over a frame of wooden poles. Bark houses were rectangular and made with poles covered with large overlapping strips of bark. Below, left is a photograph of tipis taken in about 1890.

A view of tipis near present day Mendota, Minnesota.

Tipi at Cedar Pass, Badlands, South Dakota.

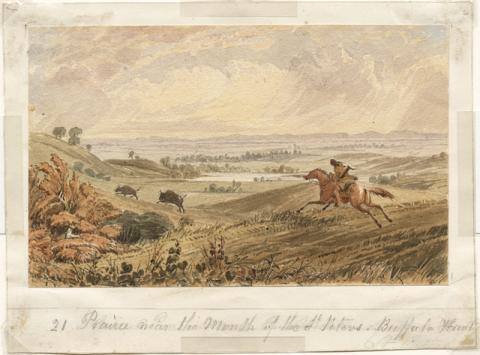

Buffalo Hunt

An interpretation of Dakota on a buffalo hunt in Minnesota by Seth Eastman in 1846-48. Dakota used bows to hunt animals for food, clothing, and shelter. Communities often moved to chosen hunting grounds, making sure no area was overhunted. Ohanwaste, or generosity toward everyone, was an important part of the Dakota hunter's life.

A Dakota bow, 1860-65.

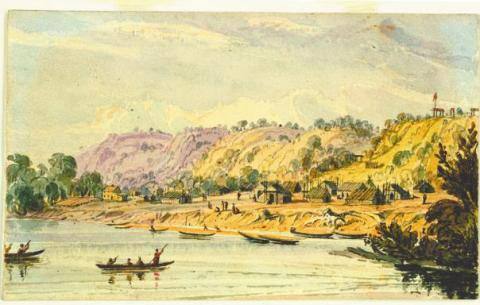

Little Crow's Village

An interpretation of Little Crow's village, Kaposia, in Minnesota, by Seth Eastman in 1846-48.