The Dakota Peace Party

When the war started, many Dakota who opposed the fighting gathered together and formed a separate camp on the Upper Sioux (Yellow Medicine) Reservation. The leaders of this "Peace Party" attempted both to stop the war and to secure the release of prisoners captured by Dakota soldiers. When the war ended many within the Peace Party, as well as some Dakota soldiers, surrendered to Col. Sibley and the U.S. military at "Camp Release" (near present-day Montevideo). After 303 Dakota men were convicted for their participation in the war, Col. Sibley removed the remaining Dakota non-combatants (approximately 1,600 people, mostly women, children, and the elderly) to Fort Snelling where they spent the winter in a cramped internment camp for civilians. Between 130 and 300 people died from illness within the camp, and the following spring they were forcibly relocated to the Crow Creek reservation in Dakota Territory.

Theme:

1862Topics:

FactionsPermissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at Copyright and Use Information.

Resources for Further Research

Secondary

Anderson, Gary Clayton, Woolworth, Alan R. Through Dakota Eyes: Narrative Accounts of the Minnesota Indian War of 1862. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1988.

Key People

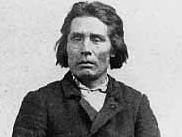

Taopi

Taopi was born in Kaposia, Little Crow's village. After the Treaty of Mendota in 1851, the village was removed to a reservation near the Lower Sioux Agency. There, Taopi took on farming, eventually becoming a leader of the Dakota farmers. In 1860, he joined with Good Thunder and Wabasha, a Mdewakanton chief, in starting a school and mission on the reservation called the Hazelwood Republic.

During the U.S.-Dakota War, Taopi was a member of the Peace Party and worked to protect captives. He was imprisoned after the war, but gained protection from Henry Sibley and testified against Dakota who had killed settlers. He was allowed to stay in Minnesota on Alexander Faribault's land.

"On the morning of the 18th of August, 1862 I was preparing to go down to the Mission House, the residence of our minister, the Rev. Mr. Hinman. He had promised to go with me to assist in laying out our burial lot near the new church. My child had been buried but a few days before. As I was about starting, the old man (Tah-e-m-na) came to my house and said, "All the upper bands are armed and coming down the road." I asked, "For what purpose are they coming?" He said, "I don't know." The old man had hardly gone out when Ta-te-campi came running to my house and said, "They are killing the traders." I said, "What do you mean?" He said, "The Rice Creek Indians [Shakopee's band] have murdered the whites on the other side of the Minnesota River , and now they are killing the traders." I said. "This is awful work."

As soon as he was gone I heard the report of guns. I went up to the top of my house and from there I could hear the shouts of the Indians and see them plundering the stores. The men of my band now began to assemble at my house. We counseled, but we could do nothing to resist the hostile Indians because we were so few and they were between us and the settlements. I told them not only to keep out of the disturbance but also not to go near the plunderers. Some of them obeyed me. I sent Good Thunder with a message to Wabasha, but he could not reach his house on account of the hostile Indians. The hostile Indians soon came to our village and commanded us to take off our citizen's clothing and put on blanket and leggings. They said they would kill all of us "bad talkers." We took our guns and were prepared to defend ourselves. We did not know what to do. I wanted to take my wagon and go to the whites, but I could not.

Good Thunder came back and brought news that nearly a whole company of soldiers from the fort had been killed at the Ferry. Good Thunder and Wa-ha-can-ka-ma-za and myself went into my cornfield to talk over the matter. We wanted to escape the fort that night, but we could not because we were watched. We determined to go to the whites at the first opportunity. I proposed to take two white girls who had been taken prisoners at Redwood, and take them to within a short distance of the fort, and them send them in with a letter stating that we were ready to cooperate with the whites in any way they might direct. We were ready, but the girls were afraid to go."

View full article: Taopi

Simon Anawangmani

Simon Anawangmani (He Who Goes Galloping Along) was born around 1808. A Dakota of the Wahpeton band, he was educated at Dr. Williamson's Lac Qui Parle mission. Although he had an early reputation as a warrior, he was one of the earliest Dakotas to convert to Christianity, and was later known for his prominence in the Hazelwood church, where he was an elder.

During the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862, he was a member of the Peace Party. He protected the Hazelwood missionaries and other settlers. In 1863 he was in the Dakota camp at Fort Snelling. Later that year he joined Sibley's army as a scout, serving until 1865. In 1866 he was licensed to preach in the Presbyterian church. After the Sisseton reservation was established in South Dakota in1867, he settled on land near the agency, dying there in 1891.

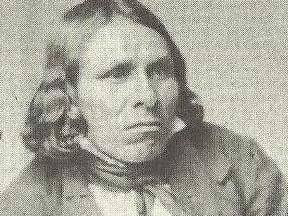

Paul Mazakutemani (Little Paul)

Mazakutemani, who was also known as He Who Shoots as He Walks or as Little Paul, was educated at Rev. Williamson’s mission school in 1835, where he learned to read and write the Dakota language. He converted to Christianity, practiced European-American-style farming, and helped organize the Hazelwood Republic, a self-governing body of Dakota farmers at Rev. Stephen Rigg’s mission on the Yellow Medicine (Upper Sioux) Reservation. During the 1862 war, Mazakutemani helped organize the "Peace Party" and served as a spokesman for Dakota who opposed the war. After the war he served as a scout during the Punitive Expeditions into the Dakota Territory.

Around 1880, Mazakutemani wrote a reminiscence about his experiences during the war:

"Sissetons, the Mdawakontons have made war upon the white people, and have now fled up here. I have asked them why they did this, but I do not yet understand it. I have asked them to do me a favor, but they have refused. Now I will ask them again in your hearing. Mdawakontons why have you made war on the white people? The Americans have given us money, food, clothing, ploughs, powder, tobacco, guns, knives, and all things by which we might live well: and they have nourished us even like a father his children. Why then have you made war upon them? You did not tell me you were going to fight with the white people; and how then should I approve it? No, I will go over to the white people. If they wish it they may kill me. If they don’t wish to kill me, I shall live. So, all of you who do not want to fight with the white people, come over to me. I have not one hundred men. We are going over to the white people. Deliver up to me the captives. And as many of you as don’t wish to fight with the whites, gather yourselves together to-day and come to me--all of you who are willing."

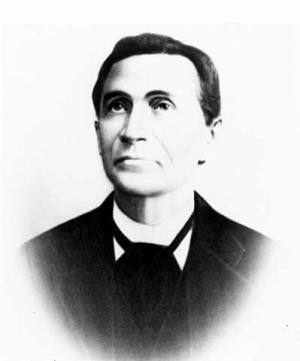

Tiwakan (Gabriel Renville)

Tiwakan (Sacred Lodge), also known as Gabriel Renville, was born in 1825 to "mixed-blood" (individuals of both European and Dakota ancestry) parents but was raised by his stepfather Joseph Akipa Renville, a Dakota man. By 1860 he had settled on a farm near the Minnesota River. When the war started, Tiwakan helped organize the "Peace Party" in opposition to the war, and worked to secure the release of the prisoners captured by Dakota soldiers. After the end of the war he and his family were sent to the internment camp for civilians at Fort Snelling, and from 1863 to 1866 Tiwakan served as a scout for the Punitive Expeditions into the Dakota Territory. Tiwakan later became a leader on the Sisseton Reservation, eventually returning to Minnesota where he died on August 26, 1892.

During the War:

"When we had gone about a mile and a half, we came to where the hostile Indians had formed a camp. As we were passing through the camp, I saw many white prisoners, old women, young woman, boys and girls, bareheaded and barefooted, and it made my heart hot, and so I said to Ah-kee-pah, Two Stars, and E-nee-hah, 'If these prisoners were only men, instead of women and children, it would be all right, but it is hard that this terrible suffering should be brought upon women and children, and they have killed many of even such as these.' I therefore had in mind to call a council, invite the hostile Indians, and appoint Mazo-ma-ne and Marpiya-wicasta (Cloud Man) to say to the hostiles that it was our wish that the prisoners should be sent home. Ah-keep-pah, Two Stars, and E-nee-hah, agreed with me in my idea, and they told me to go on and do so."

On imprisonment at Fort Snelling:

"They [the Dakota non-combatants] were then taken down on the east side of the Minnesota river, and went into camp at some distance from Fort Snelling. Shortly after this the camp was moved again, being located close to the Minnesota River. These camps were always well guarded, but in spite of that many of the horses and oxen belonging to the Indians were stolen, including three horses that belonged to myself and Charles Crawford [Gabriel’s half brother] …. Then a fence was built on the south side of the fort and close to it. We all moved into this inclosure [sic], but we were so crowded and confined that an epidemic broke out among us and children were dying day and night, among them being [Solomon] Two Stars’ oldest child, a little girl. . . . The news then came of the hanging at Mankato. Amid all this sickness and these great tribulations, it seemed doubtful at night whether a person would be alive in the morning. We had no land, no homes, no means of support, and the outlook most dreary and discouraging. How can we get lands and have homes again, were the questions which troubled many thinking minds and were hard questions to answer."

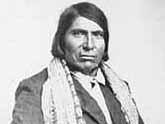

Wabaṡa

"We think our Great Father may have forgotten his Red children & our hearts are very heavy — the Agents he send to us seem to forget their father’s words before they reach here for we often think they disobey what he has said. . . . You have said you are sorry to see my young men engaged still in their foolish dances--it is because their hearts are sick. They don’t know that whether these lands are to be their home or not."

Wabaṡa to Bishop Whipple, 1862

Chief Wabaṡa (also known as Wabasha, Wapasha, or Tahtapesaah), a member of the Mdewakanton band of Dakota, lived on a farm on the Lower Reservation by the Agency. During the U.S.-Dakota War, there were divisions between groups of Dakota people who were for or against the fighting. Wabaṡa joined a group of Dakota called the Peace Party whose aim was to bring people to safety.

After the war, Wabaṡa was exiled to Crow Creek in South Dakota, and later to Santee, Nebraska.