"You know how the war started — by the killing of some white people near Acton [township], in Meeker County. I will tell you how this was done, as it was told me by all of the four young men who did the killing. These young fellows all belonged to Shakopee's band. Their names were Sungigidan (“Brown Wing”), Kaomdeiyeyedan (“Breaking Up”), Nagiwicakte (“Killing Ghost”), and Pazoiyopa (“Runs Against Something When Crawling”)."

"You know how the war started — by the killing of some white people near Acton [township], in Meeker County. I will tell you how this was done, as it was told me by all of the four young men who did the killing. These young fellows all belonged to Shakopee's band. Their names were Sungigidan (“Brown Wing”), Kaomdeiyeyedan (“Breaking Up”), Nagiwicakte (“Killing Ghost”), and Pazoiyopa (“Runs Against Something When Crawling”)."

Wambditanka (Big Eagle) later identifying the young Dakota men involved in the incident at Acton.

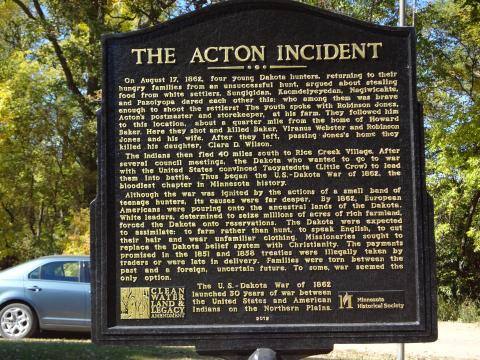

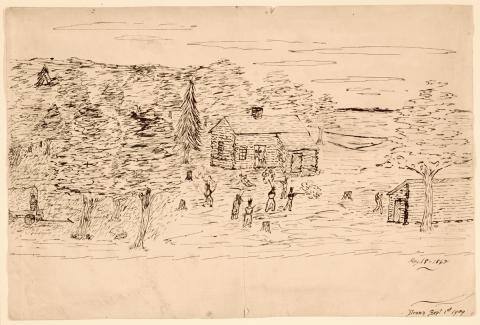

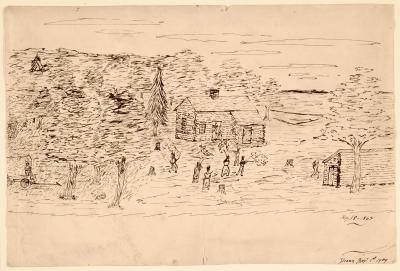

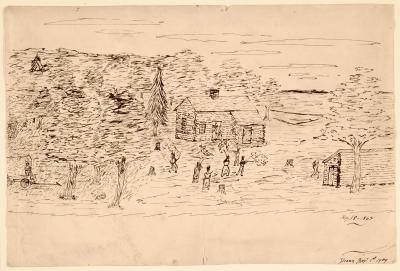

The incident in Acton Township, near present-day Grove City, Minnesota, is often cited as the moment when the U.S.-Dakota War began.

On Sunday, August 17, 1862, four young Dakota men of the Wahpeton band were returning from hunting. Upon seeing some chicken eggs in a nest at the farm of a white settler, there was a disagreement whether or not to take the eggs. When one refused, his companion dared him to prove that he was not afraid of the white man's reaction. The Dakota men proceeded to engage a white man nearby, Robinson Jones. Following him to a white homestead where some white settlers were gathered, they suggested a shooting match between them and the white men present. After shooting, the Dakota reloaded their guns and fired on the white men and women present, killing Robinson, Ann Baker, Howard Baker, and Viranus Webster. As the Dakota men left, they killed 15-year-old Clara Wilson at Jones' place.

The four men hurried back to their village at Rice Creek. After hearing their story, Red Middle Voice, a village chief, conferred with Sakpedan (Shakopee) and Taoyateduta (Little Crow). After much debate, they decided to go to war.

"You know how the war started — by the killing of some white people near Acton [township], in Meeker County. I will tell you how this was done, as it was told me by all of the four young men who did the killing. These young fellows all belonged to Shakopee's band. Their names were Sungigidan (“Brown Wing”), Kaomdeiyeyedan (“Breaking Up”), Nagiwicakte (“Killing Ghost”), and Pazoiyopa (“Runs Against Something When Crawling”)."

"You know how the war started — by the killing of some white people near Acton [township], in Meeker County. I will tell you how this was done, as it was told me by all of the four young men who did the killing. These young fellows all belonged to Shakopee's band. Their names were Sungigidan (“Brown Wing”), Kaomdeiyeyedan (“Breaking Up”), Nagiwicakte (“Killing Ghost”), and Pazoiyopa (“Runs Against Something When Crawling”)."