Memory & Commemoration

"This painting depicts a Dakota man during the Hanblecha, or Vision Quest, where the man is set out on a ledge for four days and four nights in search of his spiritual calling. He is seeking an answer to the troubles of this physical world. It is not uncommon for a man to fall away from this world from lack of food and water and protection from the elements and drift off into the spirit world, where he is given counsel over his new life."

Lyle Miller is an artist and teacher of Dakota and Lakota heritage. He teaches Dakota language and culture classes to elementary students at Crow Creek.

Many commemorative activities have taken place and are planned for the future.

View the film "Dakota 38" by Jim Miller and Smooth Feather Productions about a journey towards healing and reconciliation.

For more information about the film and to order visit Smooth Feather Productions.

View a commemoration at Fort Snelling.

Watch Elden Lawrence's story.

Read Governor Mark Dayton’s Statement Commemorating the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862

Watch the 1862 in 2012 Panel Discussion held on November 15, 2012 at the Minnesota Historical Society Annual Meeting.

Theme:

Life TodayPermissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at Copyright and Use Information.

Resources for Further Research

Multimedia

Barnes, Nancy. A deeply reported history on the U.S.-Dakota War. The Minneapolis Star Tribune, 2012.

Olson, Dan. Sheldon Wolfchild's view of the US-Dakota War. Minnesota Sounds and Voices. Minnesota Public Radio.

Websites

150th Anniversary of the U.S. - Dakota War of 1862. Brown County Historical Society.

Related Images

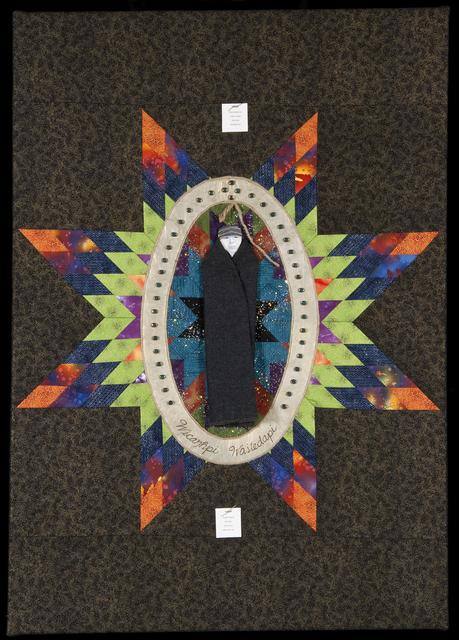

"Caske's Pardon"

"Caske's Pardon"

Mixed media sculpture / quilt by Gwen Westerman, 2012. Purchased from the 2012 "Ded Unk'unpi - We Are Here" exhibit.

In her artist statement, she writes, "'Caskes Pardon' is a response to some of the discussions today about obtaining a federal pardon for Wicanhpi Wastedapi, also known as Caske. He helped protect Mrs. Sarah Wakefield, the doctors wife, during the war but was charged with murder and condemned to die. His name was not on the list of those to be hanged. In the style of retablos, or devotional paintings, this piece incorporates the traditional star quilt with 38 + 2 blue glass beads and represents Caskes prayer for those who executed him in retaliation."

"The Weight On My Shoulders"

"The Weight on My Shoulders"

Wool woven textile by Maggie Thompson, 2012. Purchased from the 2012 "Ded Unk'unpi - We Are Here" exhibit.

In her artist statement, she writes, "The red stripes woven with gold represent and honor the 38 individuals who were hung, marking the end of the Dakota war. The lines are located over the head and shoulders to symbolize the weight of sadness that is passed down from generation to generation. The cape represents a hanging figure and mourning, which can either be lifted off or worn. With the emotional confusion that surrounds Native American history, it is important to acknowledge the past, recognize its effects on the present and insure its legacy in the future. This piece is meant to be a vehicle for remembrance, as a way to reflect on the strength and history of our people."

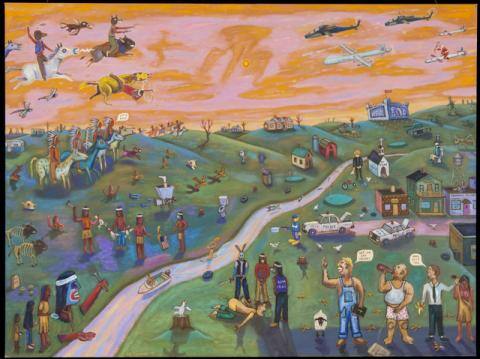

"Off the Reservation (or Minnesota Nice)"

"Off the Reservation (or Minnesota Nice)"

Oil painting on canvas by Jim Denomie, 2012. Purchased from the 2012 "Ded Unk'unpi - We Are Here" exhibit.

In his artist statement, he writes, "During my years in public education I began seeing that much of our history was not taught in school. From this experience I have been inspired to create works that speak of these historical events ignored in public education. In this piece I felt it important to express some of the facts on the events of the Dakota/U.S. war that most residents of Minnesota dont even know about. While doing research and creating the imagery many emotions arose anger, pain. I decided not to diffuse these feelings with humor or color as I normally do in many of my historical works. This painting is left raw; the tension visible through both subject matter and color. I allowed myself the emotions that come with this painful history."

"You Eat Grass Dr. Mayo"

"You Eat Grass Dr. Mayo"

Acrylic painting on canvas by Julie Buffalohead, 2012. Purchased from the 2012 "Ded Unk'unpi - We Are Here" exhibit.

In her artist statement, she writes, "This narrative points to events transpiring during the Dakota uprising of 1862. The mass execution and resulting grave became a source for medical cadavers for doctors eager for subjects to dissect. A common practice in the period, William Mayo received the body of Cut Nose, whose skeleton he kept in his home for anatomy lessons for his sons. Along with these themes, the work also suggests a connection to an ill famed quotation linked with the precipitation of the hostilities. When confronted with tribal starvation, Andrew Myrick a Minnesota trader of goods was credited as remarking, 'So far as I'm concerned if they're hungry, let them eat grass.'"

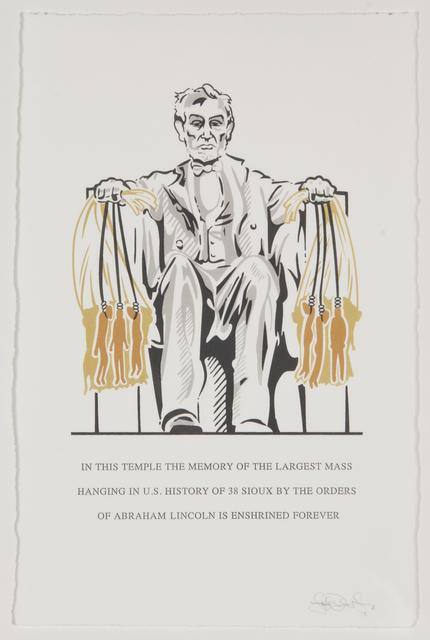

"December 26th, 1862 Memorial"

"December 26th, 1862 Memorial"

Serigraph on paper by Jodi Webster, 2012. Purchased from the 2012 "Ded Unk'unpi - We Are Here" exhibit.

In her artist statement, she writes, "History lessons in the U.S. often portray former presidents as upstanding men that gracefully and respectfully molded America."

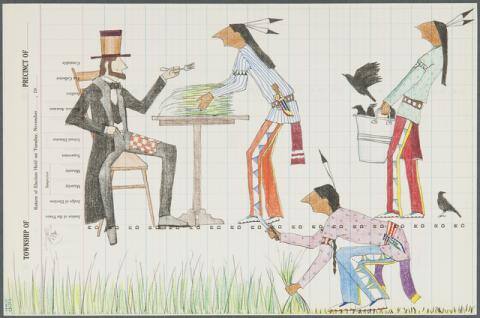

"The Crow Is To Die For!"

"The Crow Is To Die For!"

Drawing on paper (ledger art) by Dwayne Wilcox, 2012. Purchased from the 2012 "Ded Unk'unpi - We Are Here" exhibit.

In his artist statement, Wilcox writes,"Lincoln failed to provide a trust worthy agent at a time when great greed, murder, and rape of both Native and land swept the nation. During the early arrival of the Dakotas exiled from Minnesota to the new reservation at Crow Creek in South Dakota, starvation took many more lives. It has been said that Crow was the only meat available and many say thats how it got its name Crow Creek. I believe as the leader it is the full responsibility of that one man to uphold his trust. (KARMA) took care of that so its only fitting that a fresh helping of crow on his plate would be appropriate."

“For Every Great Man, There is a Great Woman”

“For Every Great Man, There is a Great Woman”

Color pencil and acrylic on paper (ledger art) by Avis Charley, 2012. Purchased from the 2012 "Ded Unk'unpi - We Are Here" exhibit.

In her artist statement, she writes, "The Dakota War killed many warriors and chiefs. Behind every great man killed was a great woman. During this tragic period in history, the women had to stay strong while ugliness was rampant in their everyday lives from the downhill battle of losing their land and livelihood. The women represent different generations and the virtues of our Dakota values. These values are courage, honesty, perseverance, and generosity and the message will be about healing, moving forward, and empowering ourselves as Dakota women despite the trauma in our history."

"1862 Sung Ite Ha"

"1862 Sung Ite Ha"

Mixed media sculpture (horse mask) by James Star Comes Out, 2012. Purchased from the 2012 "Ded Unk'unpi - We Are Here" exhibit.

In his artist statement, he writes, "The horse is respected as it is sacred and empowers the Lakota/ Dakota with its connection with the Wakinyan Oyate (which is important in Lakota/ Dakota belief). In that respect, the sacredness and utilization of the horse is vital in Lakota/ Dakota culture, as representation of honor, pride and value that are used for such ceremonies like a giveaway, honoring, or memorial of a loved one. In past, our ancestors expressed honor and pride by decorating a horse in their finest and given away as a gesture of generosity in honor of loved ones. With this in mind, I created this piece with the date 1862 in honor and memorial of the 38 Dakota that were hanged in 1862. I have utlized floral designs that represent the Dakota Oyate. Overall, this art piece is a representation of the values and way of life of the Dakota, which defines who we are as a people. But most of all, honoring and remembering what the 38 Dakota went through so our people can live and exist."

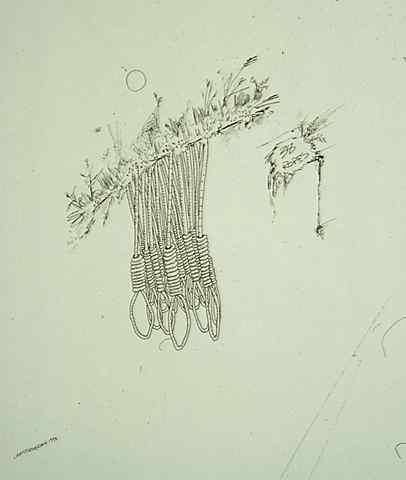

38 Ropes

"38 Ropes"

This drawing is Howard Christopherson's response to the execution by hanging of 38 Dakota men in Mankato, December 26, 1862, done in 1993.