Bibliography

Anderson, Gary Clayton. Kinsmen of Another Kind: Dakota-White Relations in the Upper Mississippi Valley, 1650-1862. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press.

Brown, Jennifer S. H. Strangers in Blood: Fur Trade Company Families in Indian Country. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1980.

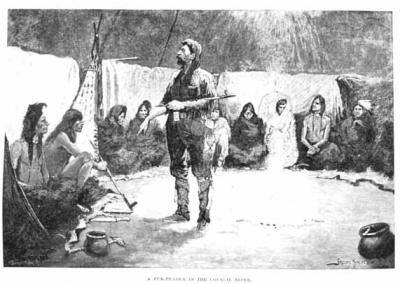

Gilman, Carolyn. Where Two Worlds Meet: The Great Lakes Fur Trade. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1982.

Green, William D. A Peculiar Imbalance: The Rise and Fall of Racial Equality in Early Minnesota. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2007.

Nelson, George. My First Years in the Fur Trade: The Journals of 1802-1804. Edited by Laura Peers and Theresa Schenck. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2002.

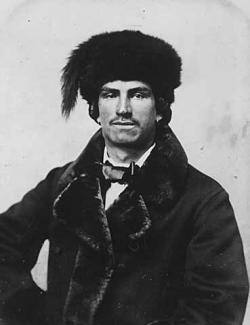

Nute, Grace Lee. The Voyageur. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1955.

.jpg)

.jpg)