Camp Release

"I surrendered at Camp Release and gave my gun to Samuel J. Brown. He put me under guard, but said I would not be a prisoner very long. I was a prisoner for four years, being sent to Rock Island. Nothing was proved against me except that I was in some of the battles against the whites. I took no part in killing the settlers and was opposed to such work."

"I surrendered at Camp Release and gave my gun to Samuel J. Brown. He put me under guard, but said I would not be a prisoner very long. I was a prisoner for four years, being sent to Rock Island. Nothing was proved against me except that I was in some of the battles against the whites. I took no part in killing the settlers and was opposed to such work."

Wakandayamani (George Quinn), 1898

On September 23, Henry Sibley defeated a Dakota force led by Little Crow at Wood Lake. Three days later, the Dakota Peace Party turned over hostages at a spot that became known as Camp Release. The Dakota delivered more than 269 captives immediately; within a few days, a total of about 285 captives were handed over. Sibley later wrote,

"The Indians and half-breeds assembled . . . in considerable numbers, and I proceeded to give them very briefly my views of the late proceedings; my determination that the guilty parties should be pursued and overtaken, if possible, and I made a demand that all the captives should be delivered to me instantly, that I might take them to camp."

On September 28, 1862, two days after the surrender at Camp Release, a commission of military officers established by Henry Sibley began trying Dakota men accused of participating in the war. Several weeks later the trials were moved to the Lower Agency, where they were held in one of the only buildings left standing, trader François LaBathe’s summer kitchen.

Theme:

1862Topics:

Aftermath of WarPermissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at Copyright and Use Information.

Bibliography

Anderson, Gary Clayton, Woolworth, Alan R. Through Dakota Eyes: Narrative Accounts of the Minnesota Indian War of 1862. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1988.

Monjeau-Marz, Corinne L. The Dakota Indian Internment at Fort Snelling, 1862-1864. St. Paul: Prairie Smoke Press, 2005.

Resources for Further Research

Primary

Anderson, Gary Clayton and Alan R. Woolworth. Through Dakota Eyes: Narrative Accounts of the Minnesota Indian War of 1862. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1988.

Websites

Sibley and the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862. Historic Fort Snelling.

Secondary

Monjeau-Marz, Corinne L. The Dakota Indian Internment at Fort Snelling, 1862-1864. St. Paul, MN: Prairie Smoke Press, 2005.

Key People

Wakandayamani (George Quinn)

I am half white man and half Indian, and I learned to read and write the Sioux language at Lake Calhoun under the instruction of the Pond brothers. But I never learned to speak English and I was raised among the Indians as one of them. So when the outbreak came I went with my people against the whites. I was 19 years old and anxious to distinguish myself in the war, but I had no wish to murder anyone in cold blood, nor did I; nobody ever accused me of such a thing. I fought the white soldiers, but not the unarmed white settlers.

After the war, George Quinn was tried and convicted by the military commission that sentenced 303 Dakota men to hanging. He received a reprieve and was sent to prison in Davenport, Iowa, until he was pardoned in 1866. He then moved to the Santee Reservation in Nebraska Territory. He died at Morton, Minnesota, in 1915.View full article: Wakandayamani (George Quinn)

Samuel J. Brown

"Weeding out the Guilty: While thus engaged and by exercising a justifiable piece of strategy I assisted in causing the arrest and in safety detaining in custody all the Indian men (except 46 who were above suspicion and three or four who had 'smelled a mice' and ran away during the night), and disarmed them and chained them in pairs together...

"Justifiable Strategy: This successful and justifiable strategy took place at the Government warehouse, built by my father when he was agent a few years before--a large, two-story building, 50 feet long, which the hostiles had burned and destroyed when they passed up on the 20th of August, but the walls of which were still standing--and was accomplished in the following manner: About a hundred yard from this building the soldiers had pitched their tents, while the Indians camped under the hill along Yellow Medicine Creek, a half or three-quarters of a mile distant. I was ordered one day to proceed to the camp and inform the Indians that the annuity roll was to be prepared the next morning and that they must all come at an early hour and present themselves to the agent at the warehouse and be 'counted.' They were delighted to learn that they were at last to get their money. The annuity payment for that year had not yet been made, and this ruse worked like a charm.

"How is was done: About 8 o'clock the next morning the Indians flocked to the warehouse anxious to be 'counted.' Major Galbraith, Captain Whitney, and two or three 'clerks' were found seated at a table behind one end of the building with pens, ink, paper, etc., hard at work on the 'rolls,' while on of the officers and myself were stationed in a doorway at the opposite and further end. As each family would step up to the table, one of the 'clerks' would rise and count or number them with his finger, one, two, three, etc., and after announcing the result with a flourish and motioning for them to pass on, a soldier would step up and escort the Indians to the other end of the building where I was stationed. As they reached the farther end and turned the corner and came in front of the doorway, I would tell the men to step inside and allow the women and children to pass on to the camp, telling them, as I was instructed to do, that the men, as heads of families, must be counted separately, as it was thought the Government would pay them extra. I would take their guns, tomahawks, scalping knives, etc., and throw them into barrels, telling them they would be returned shortly. In this way we succeeded in arresting and safely detaining in custody 234 of Little Crow's fiercest warriors. And since the Indian men outnumbered the soldiers two to one, and were fully well armed, I think that in this case, the end justified the means.'"

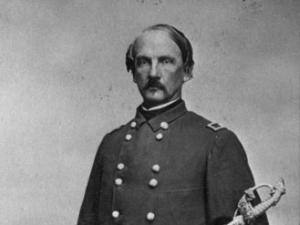

Henry H. Sibley

In 1834, Henry Sibley became a partner in the American Fur Company and settled in Mendota, Minnesota. Like a number of other traders, Sibley entered into a relationship with a Dakota woman, Red Blanket Woman. Their relationship produced a daughter, Helen Sibley, before the couple parted to live separate lives. Sibley acknowledged his daughter, protected her interests and education, and remained involved in her life. After the fur trade dwindled, Henry Sibley became a successful businessman, investing in lumbering, river transportation, railroads, and land. He played a pivotal role in the 1851 treaty negotiations and later commanded U.S. troops during the war and on the 1863 punitive expeditions. From 1867-70, he served as president of the Minnesota Historical Society.

During the war, Sibley was vilified in the press for his slowness in advancing to Fort Ridgely to liberate captive settlers. He wrote to his wife on September 4, 1862:

"I see . . . that the people are dissatisfied with my slow advance. Well, let them come and fight these Indians themselves, and they will [have] something to do besides grumbling. I have told Gov. R. in my dispatch that he can have my commission when he sees fit, as I would be too glad to let some one take my place. . . . I have not slept more than an hour in two nights, and have been in the saddle almost [all] of the time for two days and nights. . . ."

Colonel Sibley to Governor Ramsey, August 25, 1862:

"My heart is steeled against them, and if i have the means, and can catch them, I will sweep them with the besom of death."

Sibley convened the military commission that condemned 303 Dakota men to death in the wake of the war.

Letter From Col. Henry Sibley to the Assistant Secretary of the Interior, December 19th, 1862.

"[I]t should be borne in mind that the Military Commission appointed by me were instructed only to satisfy themselves of the voluntary participation of the individual on trial, in the murders or massacres committed, either by voluntary participation of the individual on trial, in the murders or massacres committed, either by his voluntary concession or by other evidence and then to proceed no further. The degree of guilt was not one of the objects to be attained, and indeed it would have been impossible to devote as much time in eliciting details in each of so many hundred cases, as would have been required while the expedition was in the field. Every man who was condemned was sufficiently proven to be a voluntary participant, and no doubt exists in my mind that at least seven-eighths of those sentenced to be hung have been guilty of the most flagrant outrages and many of them concerned in the violation of white women and the murder of children."

Source: Executive documents, MNHS collections and Henry H. Sibley: An Inventory of His Papers at the Minnesota Historical Society and Governors of Minnesota.

Related Images

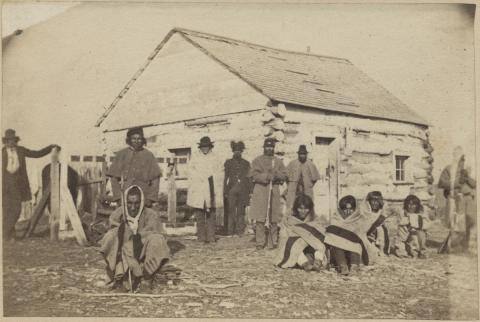

LaBathe Cabin

Adrian Ebell took this photo in 1862 of Dakota prisoners outside of the summer kitchen of François LaBathe. The cabin was used by Sibley's Military Commission as a courtroom for conducting trials of the accused.