On Sept. 2, 1862, Dakota soldiers attacked a burial party sent by Col. Henry Sibley. The Dakota kept U.S. soldiers under siege for 36 hours before a relief detachment arrived from Fort Ridgely.

Mni Sota Wakpa Stories and Reflections

Minnesota River Valley Sites

The Dakota U.S. War of 1862 that raged through southwestern Minnesota was the result of failed U.S. government Indian policies. It continues to impact the lives of many communities to this day. Uncover the places and stories that changed the course of history along the Minnesota River Valley.

“This is our ancient homeland, the birthplace of the Dakota people.”

Dr. Clifford Canku, Sisseton Wahpeton, Oral History Project Participant

Stories and Reflections

Transcript

Bdote

In awe of the prairie wind and its beauty, I listen for the shadows of voices. An ancestral memory of Forgotten rituals, Forgotten oral narratives, Forgotten humanity.

"Shadows of Voices," a poem by Gabrielle Tateyuskanskan

Welcome to the Minnesota River Valley Mobile Tour. This tour offers reflections and historical narratives at locations along the Minnesota River that address one of the most tragic periods in Minnesota history surrounding the U.S. Dakota war of 1862.

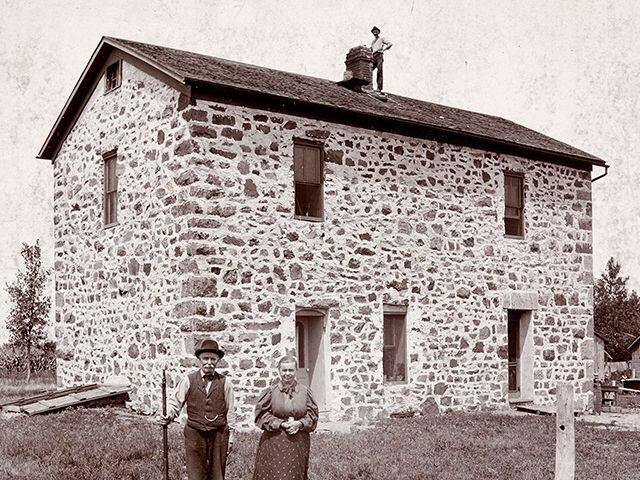

Settlers who moved onto Dakota land

O. E. Rolvaag (read by John Farrell): “The caravan seemed a miserably frail thing as it crept over the boundless prairie toward the sky line.”

Robert Buessman: “Many of our people had to leave Germany because of oppression and many problems.”

Alice Henle: “They promised the 'Land of Milk and Honey,' so they came here to find it.”

O. E. Rolvaag (read by John Farrell): “Their course was always the same - straight toward the west, straight toward the sky line...”

Sylvan Schumacher: “Why you would leave and come that far, not knowing where you’re gonna go or anything - They must have really thought it would be a nice place to live.”

Alice Henle: “You go into this area and set up a homestead or something and then it’s yours.”

Robert Buessman: “The German settlers in Chicago and in Cincinnati were told: Once you cross the Mississippi; nobody lives there. They didn’t know.”

How events surrounding the Dakota U.S. War resonate with the Dakota today

Clifford Canku: “Settlers were very much a threat to Dakota way of life. They were encroaching onto their livelihood.”

Dean Blue: “When the US Government made a pact with us, will not live up to its agreement, we have to then defend ourselves.”

Elden Lawrence: “Two whole ways of life were clashing, and one was going to lose out.”

Michael Childs: “They exiled the Dakota from the State of Minnesota.”

Dallas Ross: “My family is scattered everywhere: Sioux Valley, Pipestone Creek, Crow Creek, Santee, Flandreau.”

Judith Anywaush: “500 people were killed, and virtually a nation disappeared.”

Lavonne Swenson: “I just wonder how my relatives made it through all of that.”

Pamela Halverson: “It overwhelms me. It takes me to why my people are the way they are today? why we haven’t healed?”

Dallas Ross: “People don’t even know who they are anymore or even their family lineage.”

Carrie Schommer: “You can’t just say, 'oh, I’m going to forget about this...it will go away.' It doesn’t go away.”

Judith Anywaush: “They’re never going to give back the land; that’s never going to happen. I just want my grandchildren to know what happened and use it to be stronger in their lives.”

Clifford Canku: “We're like trees. If we don't know our roots, in terms of who we are, and how we are connected from the very beginning – to creation, and to God, and to the land. If you don't have roots, the tree falls. And it dies.”

Shadows of voices

In awe of the prairie wind and its beauty, I listen for the shadows of voices. An ancestral memory of Forgotten rituals, Forgotten oral narratives, Forgotten humanity. The conqueror in its insolence cannot hear the ancient heartbeat of the prairie. The plowed and plundered grassland has been sacrificed to a leader's arrogance. Damaged spirit is the prize for the powerful victor, given to the vulnerable, who are unable to save themselves. There is a language on the ancient landscape. Symbols that relate ideas traveling from time immemorial to humanity. Shadows of voices sustain memory in the continuous orator wind. Okiya from the wise relatives. This same prairie wind that caused pioneer women to go mad. The heart knows ceremony and its healing virtues. Medicine that can only be felt. Ancestral narratives tell of Eya's genocide and oppression. Imperialism has left its reminder, a road made of bones.

"Shadows of Voices," a poem by Gabrielle Tateyuskanskan

Tanpa Yukan / Birch Coulee

Originally called Tanpa (birch) in Dakota, Birch Coulee is a creek that flows into the Minnesota River. One of the hardest-fought battles of the Dakota U.S. War of 1862 took place nearby. Hear reflections on the spiritual connection Dakota people have with the land and their fight for survival.

Stories and Reflections

Transcript

Birch Coulee

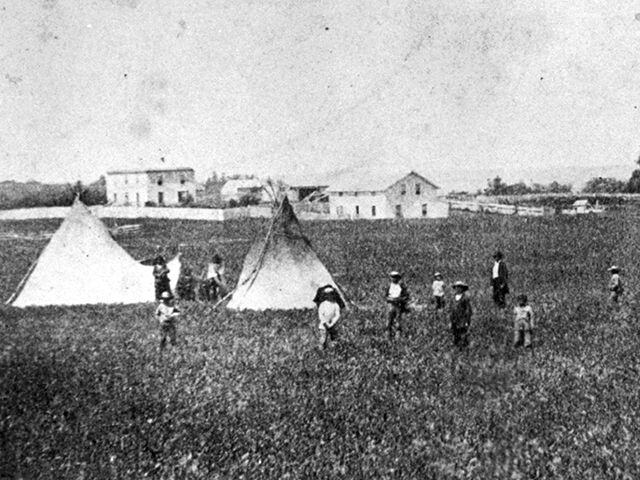

Lenor A. Scheffler reading: Tanpa Yukan, or “Place of the White Birch,” is the name given to the shallow valley where Mdewakanton and Wapekute lived on the Coulee for generations.

Narrator: The battle of Birch Coulee was fought on September 2nd and 3rd, 1862. This 36 hour battle was a major victory for the Dakota during the U.S.-Dakota war and resulted in heavy casualties to the local militia. After many transformations, the prairie is now restored to the way it would have looked in September, 1862.

Dakota spiritual connection with the land

Dallas Ross: “Birch Coulee. There’s a lot of spirits there in the form of ghosts if you believe in them.”

Clifford Canku: “Dakota relationship to the land is that she’s our mother. Our descendants have been here thousands and thousands of years. So every valley, every road, every location has a spiritual connection with us yet.”

Dallas Ross: “The land has a memory. Someday someone will be reminded of what happened there. And it probably won’t be good.”

Clifford Canku: “This country is still ours, spiritually, because it is God-given. And when God does something, he doesn't take it back.”

Reflecting back on the Dakota people’s fight for survival

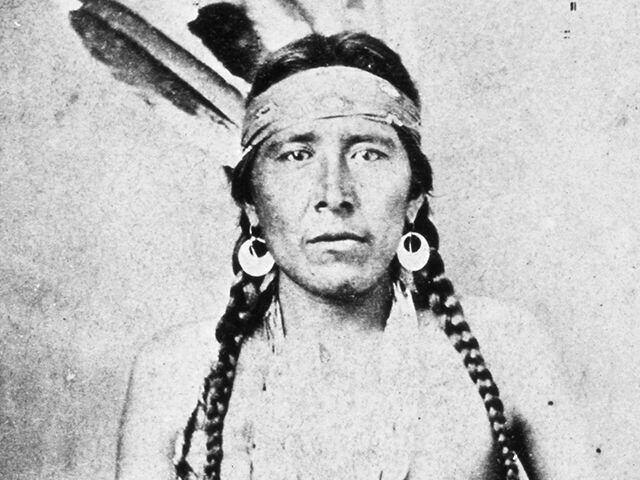

Waŋbdí Tháŋka, Big Eagle, Mdewankanton Dakota, 1894 (read by Sheldon Wolfchild): “The whites were always trying to make the Indians give up their life and live like white men--go to farming, and do as they did--and the Indians did not know how to do that, and did not want to anyway. The Indians wanted to live as they did before the treaty-- go where they pleased and when they pleased; hunt game wherever they could find it, sell furs to the traders and live as they could.”

Clifford Canku: “Settlers were very much a threat to Dakota way of life. They were moving on to Dakota lands that were encroaching on their livelihood.”

Dallas Ross: “At that point it was starting to settle in that their lives were going to be changed forever and there wasn’t a thing they could do about it.”

Clifford Canku: “What if a foreign country was encroaching onto your land? Would you retaliate, or would you just keep moving and let them take your land? We need to see the minds of the Dakota in saying 'We are warriors'."

Pamela Halverson: “Our ancestors fought for our survival. They had to go to war to fight for survival. If they wouldn’t have fought, we would have all just died. We would have starved to death.”

Sandra Geshick: “We know what happened, we know the things that they went through. They were true warriors. They went and they did what they had to.”

Dallas Ross: “They were fighting knowing that in the end it’s a futile fight. It’s probably one of the saddest places in this local area.”

More Information

Additional Resources

Visit Birch Coulee Battlefield

- Birch Coulee Historic Site Tour the self-guided site with markers explaining the battle from Dakota and U.S. soldiers’ perspectives.

Henderson

After the war, nearly 1,700 Dakota people were forced to march to Fort Snelling from Henderson. Learn more about the march and how it is commemorated today.

Stories and Reflections

Transcript

Henderson

Dale Weston: “I’ve heard some people say that’s the Minnesota Trail of Tears.”

Grace Goldtooth: “I always think about that, every time I’m in Henderson. I say a prayer.”

Narrator: In the immediate aftermath of the US-Dakota War, the United States Government force marched 1,700 women, children and elders for 6 days up to an internment camp at Fort Snelling.

Gabrielle Tateyaskanskan: “They experienced really horrific treatment at the hands of citizen-soldiers and mobs along the way, that were angry about the fighting that was taking place in Minnesota. And, they didn’t know where they were going.”

Grace Goldtooth: “They walked them all they way up through Henderson all the way to Fort Snelling They were placed into a concentration camp. And after that they were exiled from our Dakota lands.”

Dallas Goldtooth: “It’s understandable that there are Dakota people that are still sad and have grief over that event and still carry the trauma of what happened in Henderson.”

Perspectives on the internment camp at Fort Snelling

Gabrielle Tateyaskanskan: “That confluence of the Mississippi and Minnesota River is a really important site to Dakota people because it marks another geographic and ancient sacred place. And then on top of that, that’s where the concentration camp was and where people were in prison. So it has a bitter-sweet connotation there. It’s a place of rebirth and birth, but it’s also a place of great tragedy.”

Narrator: Following the U.S.-Dakota War, the United States Government punished the Dakota community. Some were hanged in Mankato, while others were imprisoned in Iowa. 1,700 Dakota women, children, and elders were marched more than 100 miles from the Minnesota River Valley up to Fort Snelling in St. Paul. During the winter of 1862, they were interned at a camp below the fort. Up to 300 Dakota did not survive the harsh winter.

Judith Anywausch: “There must have been a lot of them that died there. And what happened to them? Expendable, I guess.”

Dallas Ross: “It’s something people don’t want to remember. Unfortunately the ones that suffered through it had no way to forget. There’s immense sadness there.”

Carrie Schommer: “I get mixed feelings when I’m there, but I do know that the spirit of our people are all around there."

The Dakota commemorative walk

Gabrielle Tateyaskanskan: “The Dakota Commemorative Walk is a memorial to Dakota ancestors, elderly women and children that were force-marched in November of 1862 from what is present day Morton, Minnesota to Fort Snelling. It’s to honor our ancestors; because of them and their will to survive that Dakota people are here today.”

Narrator: The “Commemorative Walk” passes through Henderson and is supported by many in the community.

Dallas Goldtooth: “It’s amazing to see Dakota people talking about this issue. But then also it’s great to see people of Henderson, the actual town of Henderson, where they have acknowledged what their ancestors did.”

Gabrielle Tateyuskanskan: “The school there and the students at that school participate. We stay there overnight. They give us supper and breakfast and then they walk with us a little ways.”

Narrator: The walkers do face challenges...

Gabrielle Tateyuskanskan: “It’s mixed in the towns, you know, you hear discriminatory remarks; people who are angry at you and yell discriminatory things and make assumptions.”

Judith Anywausch: “A woman came out of her house and yelled at us. ‘Why don’t you guys just forget about it. You guys should just forget about it’.”

Narrator: The Dakota use the walk as a time to reflect on - and to heal from - the trauma the march left on their community.

Gabrielle Tateyuskanskan: “Being with the living relatives that come as from as far away as Montana, Canada, we’re glad to be with each other and to be able to honor our relatives and walk in our homeland.”

Grace Goldtooth: “It’s very important for us not to forget those ones that treaded through the harsh weather, and were taken without their belongings. That walk is very important for future generations. And for them to actually take that journey and take that walk, is historic.”

More Information

After the Dakota U.S. War of 1862, nearly 1,700 Dakota women, children and elders were forced to travel for six days to an internment camp at Fort Snelling. As they marched through Henderson and nearby towns, angry residents threatened and attacked the captive Dakota.

Oiyuwege / Traverse des Sioux

The Minnesota River crossing of Traverse des Sioux is the site of the 1851 U.S.-Dakota land treaty. Listen to perspectives on the treaty signings of 1851 and 1858 and their lasting impact.

“The Indians wanted to live as they did before the Treaty of Traverse des Sioux— go where they pleased...hunt game wherever they could find it, sell their furs to the traders and live as they could.”

Wanbditanka (Big Eagle), Mdewakanton, 1894

Stories and Reflections

Transcript

Traverse des Sioux

Narrator: In exchange for much needed money and goods, the Dakota gave up most of their land in two 1850s treaties and were forced to move to reservation strips along the Minnesota river. Government fraud and delay of these Dakota provisions needed for survival, set in motion the events leading into the US-Dakota war of 1862. One cause of the war was attributed to the deception around these treaties.

Perspectives on the internment camp at Fort Snelling

Pamela Halverson: “The treaties were not understood by the people. The treaties were promises set...weren't worth the paper they were written on. You know, the treaties weren't for the betterment of the Dakota people. The treaties were for the Europeans.”

Elden Lawrence: “It was a bogus document that allowed the federal government to legally steal Indian land. They made promises in those treaties that they never intended to keep. they had browbeaten and coerced the Indians to the point where they didn't have much choice.”

Walter LaBatte: “We sold all this land for x-amount of dollars per acre. But, the way it was written, the government never intended to pay us the full amount. They would pay us interest for 50 years.”

Dean Blue: “So they never actually paid for it; never paid a cent for all this vast territory.”

Robert Buessman: “If white people would have been more honest and would have kept their treaties, if they, Native Americans, had not been pushed into a corner, Had they been given the proper food and nourishment that they were promised it could have been a whole different way of life, for them; for us.”

Pamela Halverson: “Did it really matter if they signed those treaties or not? In Washington they already had the idea that they were going to exterminate the Natives into the west. So did it really even matter?”

The impact treaties have on the Dakota nation

Clifford Canku: “The treaties are still valid, that the United States needs to honor those treaties and do what they need to do in order to do justice to all the Native American tribes in the United States. The treaties are the consciousness of this continent.”

Lillian Wilson: “The United States is suffering because they made so many mistakes, and that’s one of them. they still have a lot of suffering to do because they can’t say: 'We did wrong.' Until they can say that, the cloud will be lifted and then the whole nation can do good again.”

More Information

A shallow river crossing, Traverse des Sioux was a gathering place for thousands of years. When European settlers first came to Minnesota, they traded information and ideas here with Dakota hunters. It was also the site of the 1851 Treaty of Traverse des Sioux where the upper bands of the Dakota nation ceded about half of present-day Minnesota to the U.S. government in exchange for promises of cash, goods, education and a reservation.

Additional Resources

Visit St. Peter

- The Treaty Site History Center provides information about treaties, the fur trade and Dakota culture

Camp Release

Camp Release marks the site where some Dakota leaders looking for a peaceful resolution, including Maza Ṡa (Chief Red Iron), released captives they protected during the battle of Woodlake in the Fall of 1862. Hear the story of Maza Ṡa and learn about the mounting tensions among the Dakota leading up to the war.

“I just try to imagine what it would have been like to be there.... The Indians [must have been] realizing: ‘This is over. What’s our next step?’”

Terry Sveine, New Ulm Settler Descendant, Oral History Project Participant

Stories and Reflections

Transcript

Camp Release

Narrator: The mid-1800s saw Dakota lifestyles changing. While some held on to traditional life, others adopted the white ways of farming, sparking tension. Many Dakota opposed the war and risked their lives to save whites. At Camp Release, many Dakota who didn’t fight returned captives to the army. But for their trouble, most Dakota were exiled from the state of Minnesota.

The Story of Maza Ṡa and his attempt at a peaceful resolution

Narrator: As the U.S.-Dakota War raged on, Dakota men from the Lower Sioux Agency, reached out for reinforcements from the Upper Sioux. This request forced Upper Sioux chiefs including Red Iron (or Mazasa) to make hard choices, as they knew the white soldiers would return in greater numbers.

Dallas Ross: “Mazasa wanted to try to find a peaceful solution to prevent something bad from happening. He disagreed with the battles. And, of course the warriors were going that way. The warriors decided not to challenge him but turned the captives over. The captives were probably more of a security blanket than anything else. ‘How do we extricate ourselves from this battle without getting killed completely? Well, we’ll take some hostages and we’ll do what we can.’”

Narrator: Many reluctantly joined fellow Dakota men in the fighting, while others protected white captives.

Dallas Ross: “Mazasa wanted to hopefully make things better. So Mazasa was able to take the captives and keep them relatively safe until someone came to get them.”

Narrator: As the war came to a close, the Upper Sioux Dakotas surrendered and turned over the white captives at Camp Release, with the promise of being spared prosecution by Henry Sibley and his troops. Yet another promise broken. Roughly 2,000 Dakota were taken into custody at Camp Release. Of those, more than 300 were convicted in makeshift court hearings, some lasting as short as 5 minutes.

Dallas Ross: “Whether it would have been better if he would have taken his warriors and joined the battle – hard to say. But the end result was the same. He wanted something peaceful to come out of it. It’s a place that should be remembered for what it is – a man seeking a peaceful resolution to a battle he didn’t want to fight.”

Mounting tensions within the Dakota Community leading up to the time of the Dakota U.S. War

Elden Lawrence: “The warrior faction looked at the Christian Indians as traitors. There was a whole cultural renewal or revolution taking place - two whole ways of life were clashing, and one was going to lose out. The Dakota people who were Christian, they were thinking, 'Well we haven’t changed that much. What are we doing that’s different? All we’re doing is trying to farm and provide in a different way'.”

Dallas Ross: “One side of my family for the most part was a warrior side…the other side was actually, at that time, trying to find a peaceful resolution. So even in my family there were differences.”

Elden Lawrence: “I think the Dakota people said to themselves, ‘well we have to do something, necessity has to take precedence, we have to do something to keep our families alive and to maintain what we can of our culture, and this is the way we can do it'.”

Dallas Ross: “The ones that decided to try to find peaceful means, they were hoping for something better but the result was the same. The decisions of the peaceful versus the unfriendly had no impact on the result.”

More Information

In late September, after the defeat of Little Crow’s forces, a group of Dakota chiefs released white and mixed-race captives to Col. Henry Sibley. He then moved the captives to his own encampment near Montevideo, which came to be known as Camp Release. Sibley also took into custody about 1,200 Dakota, a number that grew to nearly 2,000 as more surrendered or were captured. The trials of the Dakota who took part in the war began at Sibley’s Camp Release headquarters on September 28, 1862. Sibley later moved his troops and the prisoners to the Lower Sioux Agency, where the trials continued.

Lac qui Parle Mission

The first Dakota-language dictionary was completed at the Lac qui Parle mission, founded in 1835. Learn about the mission, American Indian boarding schools and efforts to revive the Dakota language.

Stories and Reflections

Transcript

Lac qui Parle Mission

Dallas Goldtooth: “The Dakota that you’ll find in South Dakota, North Dakota and Canada and Montana, used to live in the area of Big Stone Lake and Lac qui Parle. And they talk about it to this day that this is their homeland.”

Narrator: In 1835, missionaries arrived to establish the Lac qui Parle mission on Dakota homeland. The missionaries transcribed Dakota, a traditionally oral language, into written bodies of work. The mission was self sustaining for more than 10 years.

Tamara St. John: “The missionaries actually had to fight to be able to print, use and speak the Dakota language. So their efforts for the written language have really helped in the preservation of our language.”

Dale Weston: “And then they started putting the hymnals, the Bible and the curriculum for the children in the Dakota language.”

Narrator: The Lac qui Parle mission officially closed in 1854, due to low attendance. Less than 15 years later, the Dakota were forcibly removed from the Lac qui Parle area, following the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862.

The boarding school era

Sid Bird: “My grandfather told me the old ways are gone. We have to learn the ways of the white man. In order to take your rightful place, it will require you to go to school.”

Narrator: In the late 1800s the U.S. Government established a federal boarding school system. The aim of the boarding schools was not only to christianize the Dakota community, but also eliminate Dakota culture altogether, by forcibly removing Dakota children from their parents.

Dallas Goldtooth: “The obvious objective of the Indian boarding schools was to get Native people into the workforce of America. But the subversive objective was the idea to weaken them to the degree to where it’s just easier to erase them off the map.”

Sid Bird: “We wore army uniforms, marched to school, marched to our meals. Hut, two, three, four...everything by regimentation. Six years old.”

Lillian Wilson: “My little sister, I had to take care of her all the time. I had to always protect her and help her. She was so small. She was scared. They should have known that.”

Elmer Weston Speaking (from the 2002 MPR piece, “Exiled at Crow Creek”): "Summertime we wanted to stay at the boarding school, because we like it. Well, he'd say, 'No, you can't stay over there, you better come home. You might forget how to talk Indian,' he said. He didn't want us to lose our Indian language."

Elsie Noelle: “You lose your language when you go to boarding schools because we had signs on every door that said, “Speak English!” And if you don’t, you get strapped.”

Sid Bird: “I was there initially three years without coming home. It never occurred to me that one day I’d go home. My grandmother embraced me and she began speaking to me and I made the most tragic discovery of my life. I suddenly realized that I could no longer communicate with my grandparents. My own language had been beaten out of me.”

Narrator: Despite the attempt to eliminate the Dakota language over time, the ever resilient Dakota community remains deeply connected to the language today.

Dallas Goldtooth: "They didn’t finish the job. Their mission wasn’t accomplished. We’re still here. I’m still here. The voice you’re hearing is still here and I still can claim myself as a Dakota man.”

Importance of bringing back the Dakota language

Grace Goldtooth-Campos: (Graces speaks Dakota) "Dakota ia Tiospe Ota Yuha Win” (Grace translates into English) “My Dakota name is 'Tiospe Ota Yuha Win,' which means 'She Has Many Relatives.' (Grace speaks Dakota) “ Oceti Sakowin etanhan Bdewakantunwan hematanhan. Cansayapi heciya tanhan wahi. Cansayapi otunwe ed wati.” (Grace translates into English) “I come from the 7 Council Fires, my people are the Spirit Lake Dwellers and I live in Where They Paint the Trees Red, which is also referred to as Lower Sioux Community.” (Grace speaks Dakota) “Dakota iapi tewahinda.” (Grace translates into English) “I cherish the Dakota language.”

Dallas Goldtooth: “The Dakota language, our dialect is on the brink of extinction and we need to do something proactive here.”

Narrator: Today, there are efforts in the Dakota community to bring back the language as a way to preserve culture and spirituality.

Grace Goldtooth-Campos: “As you learn your history you’re going to learn that there’s some things that happened to our Dakota people. It’s going to build a fire within you; it’s going to be either negative, or you can turn that into something positive and drive you to learn your language, to preserve our way of life and our culture.”

Dallas Goldtooth: “Learning the language, it’s an act of bravery. For multi generations we have been told that the brand of Dakota carries no value. We are at a place within Dakota communities where that’s changing. You’re taking a stand, saying: ‘No, actually, I’m going to remain who I am and I want to learn my language. I’m not going to give that up’.”

Carrie Schommer: “The culture and the language, you can’t separate them, they’re both the same. The culture and the language it’s one.”

Dallas Goldtooth: “You may not be able to speak fluently, you may not be able to speak accurately or in the proper form, but it still gives you some connection to your ancestors, which brings contentment and pride.”

More Information

The Lac qui Parle Mission was one of the first churches and schools in Minnesota. It was built by missionaries at a trading post founded by explorer and fur trader Joseph Renville.

Additional Resources

Visit Lac qui Parle Mission

- Lac qui Parle Historic Site is located in Lac qui Parle State Park and is managed by Chippewa County Historical Society. The site features artifacts and exhibits related to Dakota people and the missionaries who worked with them. See what life was like at a pre-territorial mission.

Pezihutazizi / Upper Sioux Agency

The Upper Sioux Dakota community was forced to leave their home along the Minnesota River or killed after the Dakota U.S. War of 1862. Hear reflections on the values and enduring strength of the Dakota people.

“Families were torn apart. I just wonder how my relatives made it through all of that, how difficult a time that had to have been, to be able to survive.”

Lavonne Swenson, Lower Sioux, Oral History Project

Stories and Reflections

Transcript

Upper Sioux Agency

Shara Siyaka reading: ‘Pejuhutazizik'api,’ or, ‘the place where they dig for yellow medicine,’ land of the Sisseton and Wapeton bands. Dakota land for thousands of years.

Narrator: The Upper Sioux, or Yellow Medicine Agency, was built by the U.S. government after the Treaty of 1851, establishing a new Dakota reservation along the Minnesota River. It was an early site in the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862. It still remains a center for Dakota culture and heritage.

Enduring strength of the Dakota

Narrator: After centuries of sustaining a seasonal nomadic lifestyle, many in the Upper Sioux community turned to farming in order to adapt to reservation life.

Elden Lawrence: “There were up to 200 different so called ‘friendly’ Indian families trying to farm at that time, which is pretty good. So it was an up-and-coming community. A lot of good things might have happened there, if it hadn’t been for that outbreak.”

Narrator: But following the war of 1862, the Dakota were exiled from Minnesota, fracturing their extended family.

Lavonne Swenson: “Families were torn apart and I just wonder how my relatives made it through all of that.”

Clifford Canku: “We don’t know what happened to them as they scattered many different directions.”

Narrator: While exiled and fractured geographically, deep ancestral ties have ultimately shown the enduring strength of the Dakota.

Clifford Canku: “If you know your history, your language, your DNA, then you're proud of who you are. Our roots are still very much deeply embedded in our Dakota way of life.”

Sandee Geshick: “In every tragedy you look for that lesson to be learned. We are a peaceful people and very resilient. We bounce back from anything.”

Lasting Dakota values

Shara Siyaka reading: The word ‘Tiyospaye’ in Dakota has a much broader meaning than just the direct translation of extended family or circle of relatives. ‘Tiyospaye’ goes deeper than that.

Lenor A. Scheffler reading excerpt from Speaking of Indians, by Ella Deloria: The ultimate aim of Dakota life, stripped of accessories, was quite simple: One must obey kinship rules; one must be a good relative...every other consideration was secondary - property, personal ambition, glory, good times, life itself.

Dallas Ross: “Dakota is not a nation of people. Dakota is a way of life, a manner in which you walk through this world, ‘Dako wi choka ki eposukta.’ The Dakota way of life gives you direction. Many questions come up - the Dakota culture, Dakota spirituality or religion. In truth, there is no separation. You cannot be a Dakota without them both being together.”

Walter LaBatte: “In the Dakota way, we have what’s called ‘mdakway oyasin,’ which means all our relatives. Everything that God created is a relative of ours.”

Byron White: “If you’re Dakota and you’re Indian, how they all worked together, how they all stuck together no matter what. That’s something I’ve always tried to follow.”

Elden Lawrence: “I knew very little about the history and I was told very little about the culture, but the most tragic of it was that I was never told anything about my ancestors. And that about cuts you off from everything, because your ancestor is the thing that solidifies everything.”

More Information

The Upper Sioux or Yellow Medicine Agency was established in 1854 as a U.S. government administrative center for the Sisseton and Wahpeton bands of Dakota. Most of the agency’s buildings were destroyed in the Dakota U.S. War of 1862. One structure, the agency house, has been reconstructed to its pre-1862 condition and the foundations of other buildings are marked. In 1938, 746 acres of the area were returned to the tribe.

Additional Resources

Visit Upper Sioux Agency

- Upper Sioux Agency State Park preserves the site of the Upper Sioux Agency and includes 18 miles of trails around the Yellow Medicine River Valley.

Fort Renville

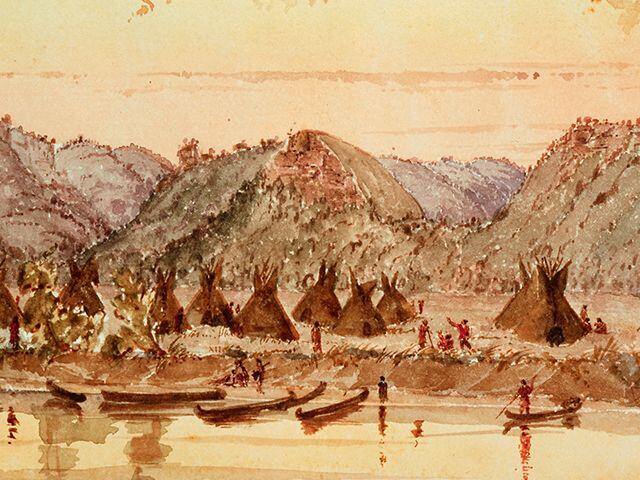

Although Fort Renville no longer exists, at one time the site boasted a large fur-trading post built in 1826 by French-Dakota trader Joseph Renville. Learn about Dakota life before the arrival of Europeans and the changes the fur trade brought to Minnesota.

“The Dakota people were here long before the European contact...we lived off the land, we were nomadic.... There was life that went on here.”

Grace Goldtooth, Lower Sioux

Stories and Reflections

Transcript

Fort Renville

Patricia Emerson: “The actual location of Fort Renville had pretty much been destroyed because of the dam that creates Lac qui Parle.”

Narrator: Fort Renville, a trading post named for the influential French-Dakota trader Joseph Renville, was a gathering place for many cultures. This place is still a reminder of the fur trade culture that once existed in Minnesota.

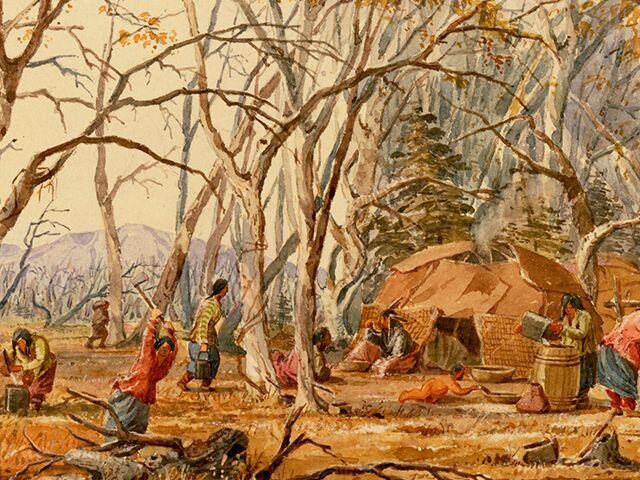

Dakota lifeways that existed in Minnesota before European contact

Peter Lengkeek: “We had a very powerful connection with ‘unci maka,’ grandmother earth. My ancestors were extremely resourceful, very hard-working. You had to be, to live out here and thrive and survive the way we did.”

Narrator: Before European contact, the Dakota lived and worked according to age-old values and traditions.

Dale Weston: “They knew how to keep things over the winter; to dry fish or dry deer, or whatever. But they didn’t do it individually It was for the community.”

Narrator: The Dakota lived according to the seasons, thriving on the land’s resources.

Gabrielle Tateyuskanskan: “Most people think, when they think of Dakota people or Sioux people they think of the buffalo being the main diet. But they netted fish and they dried fish and saved it for the winter. They harvested wild rice, they harvested maple sugar.”

Grace Goldtooth: “We knew how to use what we had here on mother earth, on ‘maka ina’.”

Dakota connection to water, both physically and spiritually

Dale Weston: “The Dakota, wherever they had to go they used the river as the fastest way of getting around. The rivers were used like highways in those days.”

Narrator: The Dakota expertly navigated the regions riverways for trade and family connections.

Gabrielle Tateyuskanskan: “They traveled to Minneapolis, you can travel along that river to Lake Traverse.”

Dale Weston: “You’d have Dakota people that would be going down the river and taking that branch that way, or taking that branch that way.”

Gabrielle Tateyuskanskan: “You can head to Canada and Dakota people followed that river way all the way to the Hudson Bay and knew about the arctic.”

Dale Weston: “They weren’t just confined to little geographical boundaries. They moved around and they intermarried with different tribes over hundreds of years.”

Narrator: For the Dakota, water is not only a means of transport, but holds spiritual significance as well.

Peter Lengkeek: “Water- we know it as the first medicine. We say ‘mni wichoni,’ water is life. Our very origin story itself comes from the water.”

Narrator: Today, many Dakota see Minnesota’s waterways as an element that needs healing.

Gabrielle Tateyuskanskan: “You can just see how dirty that Minnesota River has been allowed to become. We do have the story and the connection to place, and the spiritual understanding about why we shouldn’t do those things. Society can benefit from the knowledge that Dakota people have as knowing their ancient homeland very well.”

How life changed for the Dakota with the arrival of the fur trade

Narrator: Using the river as transportation, European fur traders flowed into Minnesota beginning in the late 1600s. They traded global goods to American Indians for furs.

Tamara St John: “They came in and lived amongst the people and it wasn’t such a controversy. They just became a people along with them. They became a part of the life of the Dakota.”

Narrator: Marriages between Dakota and Europeans created a cultural melting pot.

William Beane: “Our family might be a little more unique than some of the other families here because of our Dakota and white ancestry. We are descended from fur traders. We are descended from military men that were at Fort Snelling. So there is this interaction of all of these people in Minnesota.”

Narrator: For 200 years, the fur trade existed in relative peace until traders starting taking advantage of Native relationships.

Sid Bird: “The fat is called wasin. Wasicu – takers of fat. That’s what they called the white man. That was the first encounter with the European fur traders. They controlled the trade. Indians depended on the traders for food and clothing.”

Narrator: The fur trade marked the beginning of the end of traditional Dakota lifeways. As more settlers came to the area, the more the Dakota had to lose.

Dale Weston: “The traders came in and they would want to make a deal: ‘Oh, we want this little island over here; it’s worth nothing. We’ll give you some guns, or some of these goods, clothes or whatever, for this little piece right here.’ And then a lot of times when treaties were signed, a lot of important families were probably doing something else - they might have been ricing, they might have been buffalo hunting. And then they’d come back and they’d discover that some deal had happened.”

More Information

The fur trade existed in Minnesota for 200 years and marked the beginning of Dakota and European contact. French-Dakota trader Joseph Renville was influential in Dakota-European relations and in 1835 he invited missionaries to start the Lac qui Parle Mission nearby.

Additional Resources

Visit Fort Renville

- Fort Renville was located in what is now Lac qui Parle State Park

Mahkato / Mankato

Mahkato (Mankato) means “Blue Earth” in Dakota and is a city located on the Minnesota river. At the end of the Dakota U.S. War, 38 Dakota men were hanged in Mankato on December 26, 1862 in the largest mass execution in U.S. history. Learn about the legacy of the Mankato hangings and how their effects are still felt today.

“There are descendants there, still living in Mankato from 1862. I met a woman there who is the granddaughter of the man that cut that rope, and she met us there at the hanging site and we just held each other and cried. It was very healing for her, and for me also.”

Pamela Halverson, Lower Sioux, Oral History Project Participant

Stories and Reflections

Transcript

Mankato

Clifford Canku: “What would you do if you were promised thousands of dollars? If you moved to a smaller portion of land and the United States said: 'We'll feed you, we'll give you implements so you can be farmers.' Bu,t when you did move onto those small pockets of land, you were starving. Your children were starving, I would fight. I would fight today even though I knew it would be futile. Because you're going to die anyway. You're going to starve.”

Narrator: The Dakota did fight in the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862. Even with casualties on both sides at the end of the war, the Dakota were outnumbered.

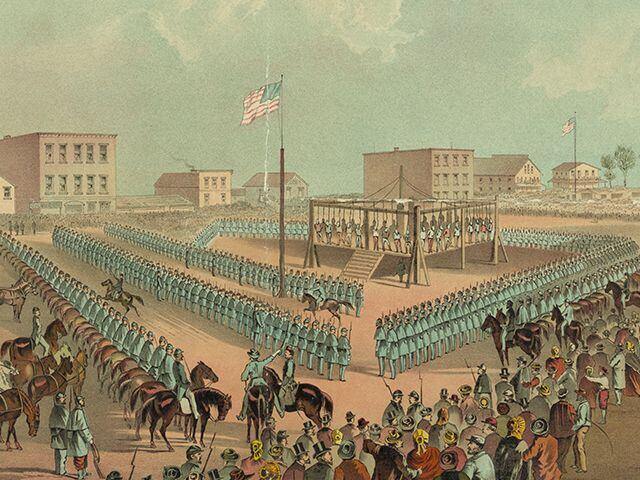

John LaBatte: “Originally three hundred and three were sentenced to hang. President Lincoln had his people narrow it down to thirty-eight.”

Narrator: On December 26, 1862, 38 Dakota men were hanged in Mankato, in the largest mass execution in United States history.

Perspectives on the Mankato hanging

Byron White: “All I could think of when we were standing there was that Abraham Lincoln freed the slaves and hung us.”

Narrator: The hanging in Mankato, left scars on both Dakota and settler descendants.

Sandee Geshick: “The first time that I found out where the actual site was when I went there, it was emotional. But when you think of our warriors that were hung there and the sacrifice that they made for me and all my people, it makes it a little bit easier to know that they sacrificed so we can have what we have today.”

Fred Juni: "I think it's a blemish on our history. I think it's terrible. There was hardship, and grief and agony on both sides of the issue. It still seems that it was hanging for the sake of hanging. It was to show that the whites were here to stay and that they were the dominant society and that the Indians were on the way out, so to speak.”

Sandee Geshick: “You can almost put yourself back in time and wonder, 'what they were they actually thinking?' And they were brave to go, walk up there, knowing that they were facing death. They were going to meet their Creator. And I’m sure they knew that they’d be seeing their relatives that went before them.”

Peter Lengkeek: “There are families of Minnesota, their ancestors settled here. Their ancestors were killed by my ancestors. They need that healing also.”

How the Dakota commemorate the Mankato hanging

Narrator: For many years the site of the hanging in Reconciliation Park was marked by a bison statue.

Grace Goldtooth: “I’m assuming that there’s a lot of residents within even Mankato that aren’t even aware of what that is. It's not just this big buffalo just there, and everyone’s just like, ‘Oh that’s just an Indian buffalo’ whatever. It’s really hard to capture what exactly took place right there in that place, and how to really make sure that everybody’s aware of that."

Dallas Goldtooth: “People in American society have short term memory loss. If there’s not a physical monument, if there’s not a granite plaque or whatever may be there, they lose all sort of personal connection to that history. That’s something that happened to their great-grandparents or their great-great-grandparents.”

Grace Goldtooth: “This is really something that people really need to take serious and look at and really pay attention to it.”

Gabrielle Tateyuskanskan: “Public acknowledgement is really important, and it’s a critical piece I think that's missing. So that people will never forget who the 38 were and the sacrifice that they made so that Dakota people could survive.”

Narrator: In 2013 a new monument was erected adjacent to the bison statue to commemorate the 38 men executed there. Each year, they are also remembered during an annual horse ride from the Lower Brule Indian reservation in South Dakota to Mankato, Minnesota.

Tamara St John: “The whole Dakota 38 Ride isn't just about remembering or honoring the Dakota 38, or those that were hung. It’s really about healing. We have to educate our young people and ourselves that we are not the places that we’ve been exiled to. We are one people, the Dakota Oyate, a part of the Tatanka Oyate.”

More Information

Of the hundreds of Dakota people who surrendered or were captured during the Dakota U.S. War, 303 men were convicted in a military court. At the urging of Bishop Henry Whipple, President Abraham Lincoln reviewed the convictions and commuted the sentences of 264 to prison terms. Lincoln then signed the order condemning 39 men to death by hanging.

One prisoner was granted a reprieve just before the sentencing was carried out. The remaining 38 men were hanged at Mankato on December 26, 1862 — the largest mass execution in U.S. history.

Additional Resources

Visit Mankato

- Reconciliation Park. On the site of the execution, this park was built through a collaboration of the Dakota and Mankato communities.

- The Blue Earth County Heritage Center preserves, displays and celebrates Dakota culture.

Cansa’yapi Otunwe / Lower Sioux Agency

The village of Caŋsayapi, known today as the Lower Sioux Agency, was one of two Indian agencies established to be the administrative centers of Dakota reservations resulting from the Treaties of Traverse des Sioux and Mendota. Gain insights into the Dakota people’s connection to land and home along the Minnesota River Valley and how the war changed this.

“I’m standing in a place where my ancestors were... and I wonder what they were thinking when they were here...? It gives me comfort to know that they stood right here.”

Sandra Geshick, Lower Sioux, Oral History Project

Stories and Reflections

Transcript

Lower Sioux Agency

Cecelia Campbell Stay, Anglo-Dakota, 1882 (read by Lenor A. Scheffler): “Lower Sioux Agency was a neat little village built on the top of the hill 12 miles west of Fort Ridgely. A belt of timber was on one side facing the river and on the other, prairie.”

Narrator: The U.S. government built the Redwood, or Lower Sioux Agency in the 1850s. It served as a hub for Dakota, Anglo-Dakota, French-Dakota and European settlers. It was the first location of the U.S.-Dakota war of 1862.

How the Dakota U.S. War impacted the people and land

Narrator: Following the War of 1862, the US government exiled the Dakota from Minnesota, even those who had no involvement in the war, tearing families apart.

Michael Childs: “They exiled the Sioux – they called them, the Dakota - from the State of Minnesota, which included my grandparents, of course. They were taken by barge down the Mississippi and then up the Missouri, up to Santee, Nebraska. Also Crow Creek. And, I mean, that was a desolate place and a lot people died."

Narrator: The US government promised to punish only those who fought in the war. However, more than 300 Dakota were convicted in makeshift tribunals, some lasting as short as 5 minutes.

Sandra Geshick: “It gives you peace to know that I’m standing in a place where my ancestors were. I wonder what they were thinking when they were here. But it gives me comfort to know that they stood right here. They knew.”

Pamela Halverson: “To be Dakota in Minnesota- what they went through. It overwhelms me. It takes me to why my people are the way they are today, why we haven’t healed. It takes me back to praying for those ancestors. I’m here because they survived.”

Stories and reflections about land and home before the war

"There is a language on the ancient landscape. Symbols that relate ideas traveling from time immemorial to humanity. Shadows of voices sustain memory in the continuous prairie wind. Okiya from Sacred and wise relatives. This same prairie wind that caused pioneer women to go mad."

“Shadows of Voices,” a poem by Gabrielle Tateyuskanskan

Narrator: For more than a hundred years before the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862, French, British, Dakota, and mixed race families coexisted on Dakota land because of economic and kinship ties.

Nancy McClure, Anglo-Dakota, 1894 (read by Shara Siyaka): “At the time of the outbreak we were living two miles from the Redwood agency, on the road to Fort Ridgely. The winter and spring before had been very enjoyable to me. There were a good many settlers in the country. We used to meet at one another’s houses in social gatherings, dancing parties and the like, and the time passed very pleasantly.”

Narrator: While life on the prairie was fraught with challenges, settlers still came to seek new opportunities.

Sylvan Schumacher: “When Leavenworth got going then, my great-grandpa, he bought a store. My great-grandma, she was a midwife because there were no doctors around in the earlier years. Why you would leave Wisconsin and come that far, not knowing where you’re gonna go or anything, with two kids. They must have really thought it would be a really nice place to live.”

Narrator: But for the Dakota, living on the land had a different meaning.

Michael Childs: “We didn't own the lands, they belonged to everybody, and so we were willing to share with others that we felt needed. It was used against us. The generosity was used against us.”

More Information

The Lower Sioux Agency was a U.S. government administrative center for the Mdewakanton and Wahpekute bands of Dakota. In the months leading up to the war, the U.S. government failed to make annuity payments owed to the Dakota and refused to provide food and supplies. These actions contributed to the growing resentment that led to the war in the summer of 1862. As tensions mounted, a reluctant Taoyateduta (Little Crow) led an attack on the Lower Sioux Agency on August 18, 1862, killing 18 traders and government employees. The Dakota then attacked settlements along the Minnesota River Valley, in a strategic effort to reclaim their homeland, killing white settlers and compelling thousands to flee.

Visit Lower Sioux Agency

- Lower Sioux Agency Historic Site: The Minnesota Historical Society gratefully acknowledges the Lower Sioux Indian Community, which manages this site. Includes exhibits on Dakota history, life and culture and self-guided trails to explore the landscape and the warehouse building.

Isan Tanka Tipi / Fort Ridgely

Built in 1853, Fort Ridgely was originally designed as a law enforcement center to keep peace as European settlers poured into the ceded Dakota lands. Learn about archaeological findings at Fort Ridgely and hear Dakota people reflect on the site today.

Stories and Reflections

Transcript

Fort Ridgely

Patricia Emerson: “From the perspective of both the Dakota and the Euro American settlers, Fort Ridgely was really critical.”

Narrator: While originally built as a place to protect newly arrived European settlers and later a training center for Civil War volunteers, in August of 1862, Fort Ridgely became a turning point in the U.S.-Dakota war, with lasting implications.

Patricia Emerson: “We have documentary evidence that some Dakota believed that if they could take Fort Ridgely, then the Minnesota River Valley would be theirs.”

Archaeological history of Fort Ridgely

Grace Goldtooth-Campos: “I think it’s important for all Minnesotans to know that the Dakota people were here long before the European contact.”

Patricia Emerson: “We still do have evidence of at least 10,000 years of Native presence. That’s something that people forget about.”

Narrator: Archaeological research reinforces what Dakota people have always known about the land.

Patricia Emerson: “In the 1930’s, an archaeologist named G. Hubert Smith directed the excavation that left the foundations that you see out there today. Quite by accident, Smith also wound up excavating an earlier occupation which represents a Native cultural tradition that archaeologists call Oneota. The artifacts date to 1300-1400 A.D. There are also prehistoric burial mounds in Fort Ridgely that were initially documented in the 1880’s.”

Narrator: Recent digs have provided even more evidence of Native presence.

Patricia Emerson: “One of the interesting things that was found several years ago was the remnants of a circle of rocks that were intended to contain a fire. The recent archaeological work did include consultation with representatives from both Lower Sioux and Upper Sioux communities. That ability to document Native presence was important to them. The heritage of Native people is really part of the heritage of everybody who calls himself Minnesotan.”

Dakota reflections on Fort Ridgely today

Tamara St. John: “When we find ourselves going to Fort Ridgely and examining this history, our role in it is one of trauma and it’s often very hard.”

Narrator: While a rich historic site to visit for many, Fort Ridgely brings up strong emotions for people in the Dakota community.

Gabrielle Tateyuskanskan: “It’s really difficult teaching your children that these forts were built to protect Euro-Americans against Indians and that their job was to kill Indians. They are difficult reminders that there’s still that attitude in America that Indians are the enemy.”

Narrator: Today’s educators in the Dakota community use Fort Ridgely as a tool to educate Dakota youth, not only about their history but also important values in the community.

Dallas Goldtooth: “We talk about the history. We tell the youth ‘this was frontier at one point, this was the western edge of the western world. And this is the site where we had a battle with the Americans; this is where the Dakota people attacked the fort.’”

Grace Goldtooth-Campos: “When I’m riding in Fort Ridgely and we’re using our Dakota language when we’re riding there, I feel like that’s a way of healing, not only for ourselves, but for the land there that once heard the language spoken so freely within the area there. This land, it appreciates that.”

More Information

While built in 1853, by 1862 Fort Ridgely was a training base for Civil War volunteers. The military outpost also saw combat during the Dakota U.S. War of 1862.

Dakota forces attacked the fort twice — on August 20 and 22, 1862. The fort suddenly became one of the few military bases west of the Mississippi to withstand a direct assault. Fort Ridgely’s 280 military and civilian defenders held out until U.S. Army reinforcements ended the siege.

Additional Resources

Visit Fort Ridgely

- Located in Fort Ridgely State Park and managed by Nicollet County Historical Society. Visitors to the Fort Ridgely Historic Site can see the ruins of this once thriving outpost and learn more about its role in the Dakota U.S. War. A Visit to the adjacent Fort Ridgely Cemetery offers more history.

Maya Kicaksa / New Ulm

Founded in the 1850s on Dakota homeland, the town of New Ulm was a destination for German immigrants on the prairie. Clashes over land rights and unfulfilled promises led to tension between the Dakota and these new arrivals. Hear descriptions of European immigrant life and the legacy 1862 left with the people of New Ulm.

“New Ulm basically became a ghost town.”

Robert Beussman, New Ulm Settler Descendant, Oral History Project Participant

Stories and Reflections

Transcript

New Ulm

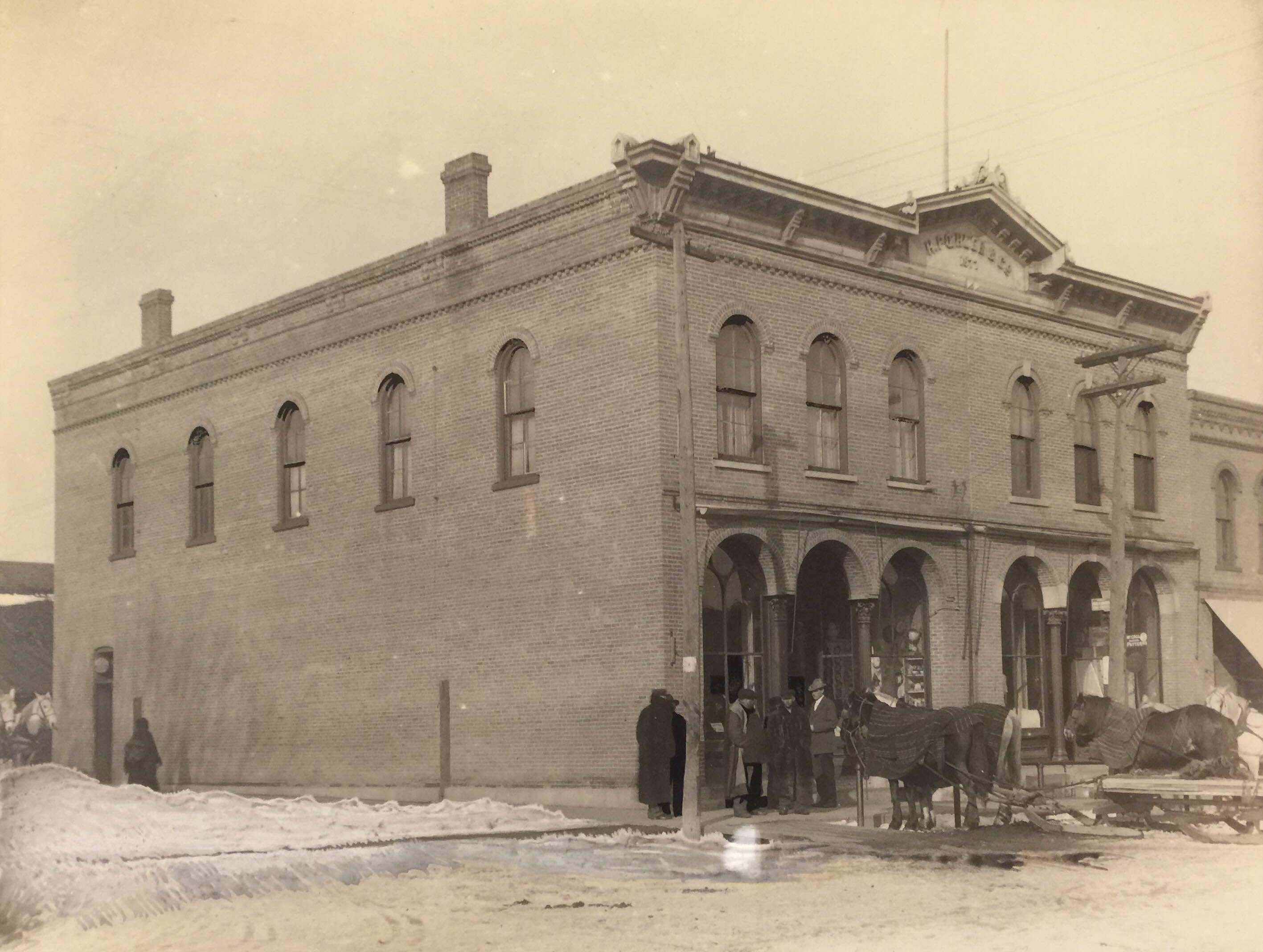

Narrator: Founded in the 1850s, New Ulm was a haven for German immigrants to start a new life on the prairie. But clashes over land rights and unfulfilled promises led to tension between the Dakota and these new arrivals, culminating in the U.S-Dakota war of 1862. Two attacks on the town during the war destroyed most buildings and left settlers to start anew or leave the area altogether.

Descriptions of European immigrant life on the prairie

Sebastian May, German settler, 1850s (read by John Farrell): "I have been on my land two years. It took me quite a time to find a suitable place to establish a home. I feel so at home here. It is as if I were still in Germany”

Fred Juni: “The founders of New Ulm - the people that originally laid it out and planted the city - had great foresight. It’s laid out by Germanic culture, very neat and orderly, and every street is straight and every block is square. And they did it based on their heritage and all the things that their instincts told them were right.”

Mary Fellegy: “Grandpa Diepolder was born in 1856. He would tell us stories when his parents came over here from Germany. There were no doctors around so he was nursed by Indians and they lived in a bark house.”

Sylvan Schumacher: “Our neighbor, Charlie Schneider, he would tell us about when he was younger that if he was supposed to catch some fish, he would get a couple sandwiches and give them to the Indian boys and then they would go down and they would take this stick when they saw this fish, and they could flip them right out of the water. When the Indian Uprising took place, they told them that they should leave immediately because the Indians were on the warpath. They packed up the wagons and they got to New Ulm before the real Uprising took place, because they warned them way ahead of time.”

Reflections on the legacy of 1862 left on the people of New Ulm

Narrator: Following two Dakota attacks on New Ulm, many settlers left to rebuild their lives elsewhere.

Robert Beussman: “New Ulm basically became a ghost town. Everybody moved and went back to St. Peter, or someplace, and then they just slowly trickled back into New Ulm and tried to restart.”

Narrator: Eventually New Ulm rebuilt and to this day the community is still processing the events of the war.

Mary Fellegy: “Quite a while ago, we had a Dakota speaking, and the first thing he said, ‘I was afraid to come to New Ulm.’ And I will never forget that statement. And to be afraid in 2000, or in the 1900s, it's terrible! This is what he opened his talk with, and I’ll never forget that.”

Fred Juni: “It impacted everyone in one way or another. It impacted the Civil War in some small way. And I think to the people of Brown County, that conflict molded a great deal of what we are. To forget that, I think it would just absolutely, absolutely almost immoral and wrong.”

More Information

New Ulm was the site of two attacks by the Dakota — on August 19 and 23, 1862. Using outlying buildings for cover, the Dakota fired on the town’s defenders and burned buildings near the river, leaving more than a third of the town in ruins.

With little food and ammunition left in New Ulm and fearful of another attack, about 2,000 residents fled to Mankato, St. Peter and St. Paul. New Ulm settlers began returning in early September. In December 1862, the town officially reorganized. Today, monuments and memorials commemorate the attacks.

Additional Resources

Visit New Ulm

- Brown County Historical Society Museum exhibit: “Never Shall I Forget - Brown County and the Dakota U.S. War”

- Frederick W. Kiesling Haus One of few structures that survived the war.

- Harkin Store Historic Site provides a glimpse of settler life after the war, with period wares still on the shelves.

Wapahasa Otunwe / Wabasha Village

Chief Wabasa (Wabasha) was a leader of the Mdewakanton band of Dakota. His community originally lived along the lower Mississippi River around Winona, Minnesota. But Chief Wabasa moved seasonally as far north as Fort Snelling. Learn about early Dakota villages and the role of chiefs in community life.

“You have said you are sorry to see my young men engaged still in their foolish dances. I am sorry.... It is because their hearts are sick. They don’t know whether these lands are to be their home or not.”

Chief Wabasa to Bishop Henry Whipple

Stories and Reflections

Transcript

Wabasa Village

Chief Wabasa (read by Tom LeBlanc): "We think our Great Father may have forgotten his Red children and our hearts are very heavy ...you have said you are sorry to see my young men engaged still in their foolish dances. It is because their hearts are sick. They don’t know that whether these lands are to be their home or not."

Narrator: The Dakota nation ranged over a vast area from what is now southern to central Minnesota and beyond. By the 1850s when the European settler population exploded, the U.S. government pressured the Dakota to leave their lands. While acting as chief of his band, others also played a vital role in the community.

Role of the Chief from a Dakota perspective

Chief Wabasha (read by Tom LeBlanc): “You have named a place for our home, but it is prairie country. I am a man used to the woods, and I do not like the prairies. Perhaps some of those here will name a place we would like better.”

Narrator: In the early 1800s, Dakota land encompassed what is now the Twin Cities, and also stretched to northern birch forests. But by the time of the 1851 treaty signing, Chief Wabasha and his band were pushed further away from these forests to a small piece of land along the Minnesota river.

Tamara St. John: “We had a beautiful life here in Minnesota and that life, to be taken away from us by the ceding of our lands. And then to be reduced to a strip along the river where we were unable to sustain ourselves; a great nation down to this.”

Dallas Goldtooth: “That’s not our original villages. Wabasha Village and Little Crow Village that were there- they were only there for 10 years, 5 years.”

Narrator: For some Dakota, their family history goes back to villages located right in the heart of Minneapolis and St. Paul.

Gabrielle Tateyuskanskan: “My grandmother would take me to Lake Calhoun and she would say ‘ this is where cloud mans village was. Tthis is where your ancestors lived at one time when they were in Minnesota.’ As a really young child I knew geographically, where my home was.”

Dale Weston: “If you go out to Lake Calhoun on the southeastern side of the lake, there’s a big stone there and it does say ‘Cloud Man’s Village’ on it. Cloud Man lived there from roughly 1820 to the late 1850’s. 'Mde Medoza' is what they called it. It had several different names but that was the one my dad used to say it is 'Mde Medoza' and that’s lake of the loons.”

Gabrielle Tateyuskanskan: “Just as all people get attached to their home and to the place where there are family memories that are rich and deep, that is true for Dakota people too.

Narrator: Archaeology confirms this long held oral knowledge of Dakota villages spanning the state of Minnesota.

Patricia Emerson: “Very close to Fort Snelling there is a documented archaeological site that appears to be the site of Black Dog’s village.”

Narrator: Today, while the Dakota people are spread across multiple states and even into Canada, Minnesota is still home.

Tamara St. John: “ Now we have youth that would say, ‘I’m Crow Creek,’ or ‘I am Flandreau.’ They forget, ‘you are a part of a much bigger family, you’re a part of an Oyate. This is your people. Those are just places.' Although at times it probably feels like Minnesota has forgotten us, we have certainly not forgotten Minnesota.”

Importance of bringing back the Dakota language

Tamara St. John: “A leader was somebody that was selected by the people. And although there were hereditary chiefs, it was probably not even really a choice that they made, so much as it was the community.”

Narrator: Different members of the Dakota leadership, including the chief, played valuable roles in the community.

Dale Weston: “Cooperative societies work together and I think that’s been the goal of the foreign governments, is to get rid of that cooperativeness among the groups. And when we become individuals and we start hoarding as individuals, then we’ve lost those values that were there in the beginning.”

Narrator: Additionally, a Dakota person might hold a position of high esteem within the community, but may not necessarily hold the title of Chief.

Dale Weston: “When there was a buffalo hunt or an elk hunt, the men would come back and there would be a feast for the community. The eldest, the one that was considered pretty much the leader - he wasn’t like a king, but he was respected because he made sure everybody had enough to eat- the grandmothers, the mothers, the children, the young men that did the hunt - and then he would eat last. From my understanding the decisions were cooperative decisions that were by consensus.”

More Information

After the Treaty of 1851, Chief Wabasa moved his people to the newly formed reservation and lived in small villages along the Minnesota River. A marker near Morton identifies where Wabasa’s band moved in 1853 after ceding millions of acres to the U.S. government. Wabasa and his people were expelled from Minnesota, even though he had opposed the war.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at Copyright and Use Information.