Topics

Category

Era

Grand Portage (Gichi Onigamiing)

Grand Portage (Gichi Onigamiing) is both a historic seasonal migration route and the traditional site of an Ojibwe summer village on the northwestern shore of Lake Superior. In the 1700s, after voyageurs began to use it to carry canoes from Lake Superior to the Pigeon River, it became one of the most profitable fur-trading sites in the region and a headquarters for the North West Fur Company.

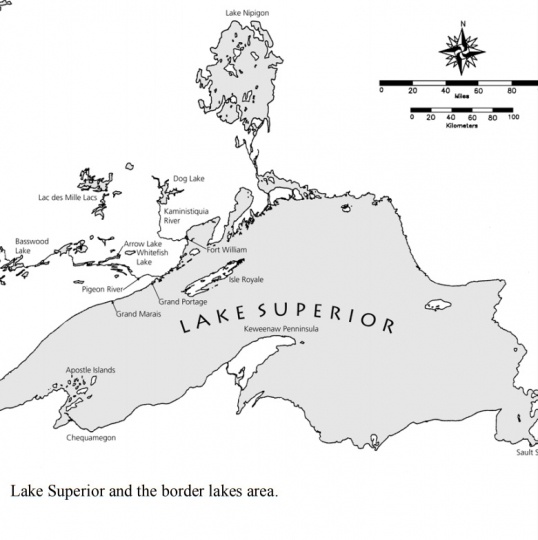

Indigenous people have used the eight-and-a-half-mile pathway that connects the Pigeon River with Lake Superior since at least the beginning of the first millennium CE. Though the river provides the fastest route from the lake to inland forests, its lower twenty-one miles are full of rapids and waterfalls. To bypass this rough stretch, Indigenous travelers carried their canoes overland and entered the river at its easternmost navigable point. Ojibwe and other Anishinaabe people called the area—and still call it—Gichi Onigamiing, the great carrying place.

Around 1680, a group of Ojibwe people migrated westward along the northern shore of Lake Superior to Thunder Bay and, eventually, Grand Portage Bay. Gichi Onigamiing became a crucial part of their seasonal cycle, which was structured around the earth’s changes and their resource needs. During the winter, they lived in hunting camps at inland sites like Brule, Whitefish, and Arrow Lakes. In the spring, they moved to maple sugar camps before returning to summer villages at Gichi Onigamiing and other sites around Lake Superior. A white cedar tree (manito gizhigans: spirit little cedar tree) growing from the rocky shore on the eastern edge of Grand Portage Bay became a sacred landmark.

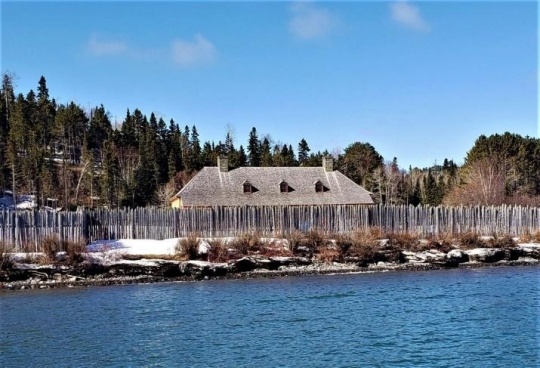

After Pierre de la Vérendrye landed at Gichi Onigamiing on August 22, 1731, the site grew into a major rendezvous point for the fur trade, and Europeans began to refer to it as Grand Portage. By 1784, the North West Fur Company was running two operations on the site: Fort Charlotte, at the western end of the portage, and Fort George, a trading depot at its eastern terminus. Company clerks expanded the depot to include, by 1793, sixteen wooden buildings: shops, private lodgings, a mess hall, an accounting office, and six storehouses, all surrounded by gated log palisades.

Activity at Grand Portage, as at other trading posts, followed a seasonal cycle. Only a few company employees stayed on site in winter to maintain buildings while the majority traveled to hunting and trapping sites. Every year in June, however, they reunited at Grand Portage for the Great Rendezvous, a two-month celebration with feasting, dancing, and socializing. There, Ojibwe hunters and trappers exchanged animal furs for traders’ goods like sugar, flour, tobacco, gunpowder, and guns.

Influential traders passed through Grand Portage and noted it in their journals, including David Thompson and Alexander Henry the Younger—both employees of the North West Company. The French-Ojibwe Collin family (Antoine and his sons Michel and Jean-Baptiste) worked in and around Grand Portage for over four decades, first for the North West Company (1790s–1821) and then for the Hudson Bay Company (1821–1830s).

Grand Portage’s heyday as a trading site arrived in the late 1790s, when the North West Company and its rival, the XY Company, competed most fiercely. Limited business resumed in 1821, when the Hudson’s Bay Company established a fort at Grand Portage Bay, and continued into the 1830s. By the 1840s, however, fur trading no longer promised large-scale profits, and companies abandoned their forts.

After the fur-trade era, Ojibwe people remained near Gichi Onigamiing. The first Treaty of La Pointe (1842) reserved the right of the Lake Superior and Mississippi River Ojibwe to use the portage. The second treaty of that name (1854) established the Grand Portage Indian Reservation, one of the seven federally recognized reservations of Ojibwe in Minnesota.

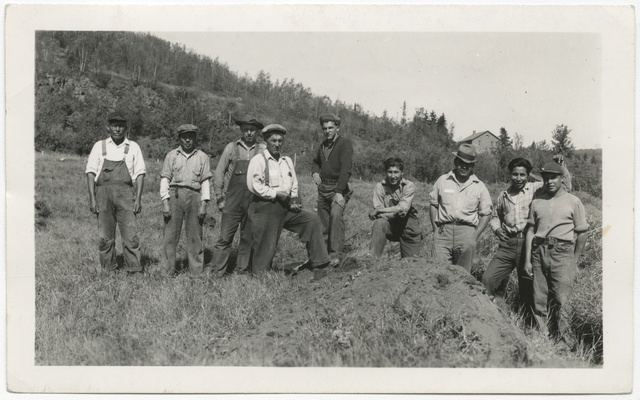

Between 1939 and 1940, workers employed by the Indian Division of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) reconstructed Grand Portage’s Great Hall on its original foundations. Twenty years later, the Grand Portage Ojibwe ceded 709.67 acres of their reservation to the National Park Service, allowing the site to become a National Monument on October 15, 1960. Fire destroyed the Great Hall on July 15, 1969, but the reconstructed palisades and East Gate remained intact. In 1974, a rebuilt Great Hall opened to the public.

Bibliography

BWCA Wild. Portage from Lake Superior to the Pigeon River (The Grand Portage).

http://bwcawild.com/MiscellaneousPage/Portages/The-Grand-Portage.html

Gilman, Carolyn. The Grand Portage Story. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1992.

Minnesota Chippewa Tribe. A History of Kitchi Onigaming: Grand Portage and its People. Cass Lake, MN: Minnesota Chippewa Tribe, 1982.

Morriseau, Norval. Legends of My People, the Great Ojibway. Selwyn Dewdney, ed. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1982.

Morrison, George, as told to Margot Fortunato Galt. Turning the Feather Around: My Life in Art. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1998.

National Park Service. Grand Portage.

https://www.nps.gov/grpo/index.htm

National Park Service. Grand Portage: Administrative History.

https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/grpo/adhit.htm

Nelson, George. My First Years in the Fur Trade: The Journals of 1802–1804. Edited by Laura Peers and Theresa Schenck. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 2002.

Nute, Grace Lee. The Voyageur. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1987 (reprint).

——— . The Voyageur’s Highway. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2002 (reprint).

Officialdata.org.

https://www.officialdata.org/1800-GBP-in-2018?amount=25000

Swan, Ruth, and Edward A. Jerome. “The Collin Family at Thunder Bay: A Case Study of Métissage.” Papers of the Twenty-Ninth Algonquian Conference 29 (December 1, 1998): 311–327.

https://ojs.library.carleton.ca/index.php/ALGQP/article/view/490/392

United States Census Bureau. American Fact Finder. Grand Portage Reservation and Off-Reservation Trust Land.

https://www.census.gov/tribal/?st=27

Van Kirk, Sylvia. Many Tender Ties: Women in Fur-Trade Society, 1670–1870. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1980.

White, Bruce M. “Grand Portage as a Trading Post: Patterns of Trade at ‘The Great Carrying Place.’” Report prepared for the National Park Service, September 2005.

https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/grpo1/fur_trade.pdf

Woolworth, Alan R. “The Great Carrying Place: Grand Portage.” In Where Two Worlds Meet: The Great Lakes Fur Trade, 110–115. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1982.

Related Resources

Primary

III.7

Grand Portage footage [motion picture], ca. 1940–1949

Description: Footage of the Grand Portage and Pigeon River area in northern Minnesota, the stockade at Grand Portage National Monument, and Ojibwe people filmed by Elmer Albinson. Some of the footage may have been used in Albinson's film My Chippewa Home Revisited.

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/sv000171.xml

Auger, Donald J., and Paul Driben, eds. Grand Portage Chippewa: Stories and Experiences of Grand Portage Band Members. Grand Portage, MN: Grand Portage Tribal Council, 2000.

P851

Peter Pond papers, 1773–1777

Manuscript Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

Description: Two versions of Pond's narrative of his early life as a fur trader and soldier in the "Northwest" and along the St. Peters (Minnesota) River; fur trade accounts used at Grand Portage, 1773-1775, by Pond and his partner, Felix Graham; and a list of supplies to be used by Pond and Greves at Grand Portage (1775).

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/p0851.xml

Secondary

Andrews, Frances. “Grand Portage.” Outdoor America, March 1939.

Cochrane, Timothy. Gichi Bitobag, Grand Marais: Early Accounts of the Anishinaabeg and the North Shore Fur Trade. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2018.

Related Images

Beginning of the Grand Portage trail

All rights reserved

Holding Location

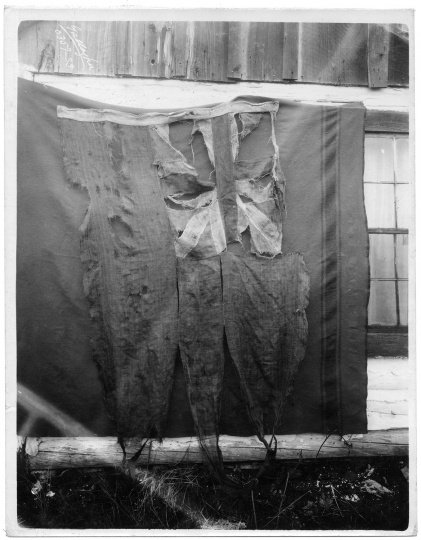

British flag that flew at Grand Portage

The British flag that flew at Grand Portage in the late 1700s; photograph ca. 1960.

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

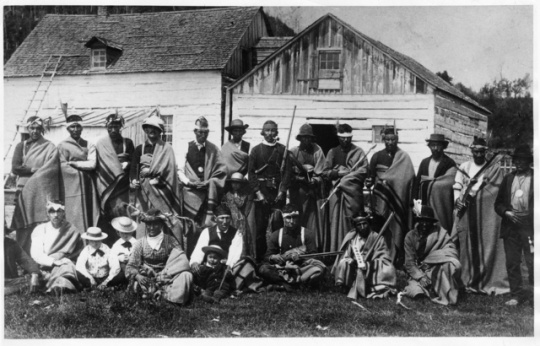

Group of Ojibwe at Grand Portage

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

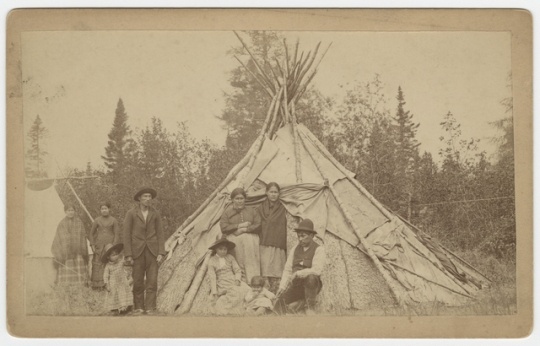

Group of Ojibwe in front of a wigwam at Grand Portage

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

Grand Portage Bay

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

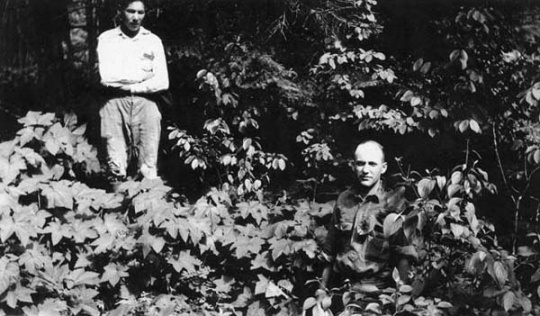

Cecil W. Shirk and Paul LaGarde at the site of Fort Charlotte

Holding Location

More Information

Ojibwe man on Grand Portage trail

Holding Location

More Information

Site of Fort Charlotte on the Pigeon River

Holding Location

More Information

Civilian Conservation Corps workers at Grand Portage

Holding Location

More Information

Dedication of Grand Portage National Historic Site

Holding Location

More Information

Manito gizhigans (spirit little cedar tree)

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

Map of Lake Superior and its border lakes

Public domain

Holding Location

Articles

Sign at Grand Portage trailhead

All rights reserved

Holding Location

Recreation of the North West Company depot at Grand Portage

All rights reserved

Holding Location

Bird’s-eye view of the reconstructed Grand Lodge on Grand Portage Bay

Public domain

More Information

Related Articles

Turning Point

In 1802, the North West Company builds Fort William (Kaministikwia) to replace its base of operations at Grand Portage. As a result, the volume of trading at Grand Portage begins to decline.

Chronology

ca. 0 CE

late 1600s

ca. 1680

1730s

1731

1767

1799

1799/1800

1802

1805

1825

1836

1854

1972

Bibliography

BWCA Wild. Portage from Lake Superior to the Pigeon River (The Grand Portage).

http://bwcawild.com/MiscellaneousPage/Portages/The-Grand-Portage.html

Gilman, Carolyn. The Grand Portage Story. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1992.

Minnesota Chippewa Tribe. A History of Kitchi Onigaming: Grand Portage and its People. Cass Lake, MN: Minnesota Chippewa Tribe, 1982.

Morriseau, Norval. Legends of My People, the Great Ojibway. Selwyn Dewdney, ed. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1982.

Morrison, George, as told to Margot Fortunato Galt. Turning the Feather Around: My Life in Art. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1998.

National Park Service. Grand Portage.

https://www.nps.gov/grpo/index.htm

National Park Service. Grand Portage: Administrative History.

https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/grpo/adhit.htm

Nelson, George. My First Years in the Fur Trade: The Journals of 1802–1804. Edited by Laura Peers and Theresa Schenck. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 2002.

Nute, Grace Lee. The Voyageur. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1987 (reprint).

——— . The Voyageur’s Highway. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2002 (reprint).

Officialdata.org.

https://www.officialdata.org/1800-GBP-in-2018?amount=25000

Swan, Ruth, and Edward A. Jerome. “The Collin Family at Thunder Bay: A Case Study of Métissage.” Papers of the Twenty-Ninth Algonquian Conference 29 (December 1, 1998): 311–327.

https://ojs.library.carleton.ca/index.php/ALGQP/article/view/490/392

United States Census Bureau. American Fact Finder. Grand Portage Reservation and Off-Reservation Trust Land.

https://www.census.gov/tribal/?st=27

Van Kirk, Sylvia. Many Tender Ties: Women in Fur-Trade Society, 1670–1870. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1980.

White, Bruce M. “Grand Portage as a Trading Post: Patterns of Trade at ‘The Great Carrying Place.’” Report prepared for the National Park Service, September 2005.

https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/grpo1/fur_trade.pdf

Woolworth, Alan R. “The Great Carrying Place: Grand Portage.” In Where Two Worlds Meet: The Great Lakes Fur Trade, 110–115. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1982.

Related Resources

Primary

III.7

Grand Portage footage [motion picture], ca. 1940–1949

Description: Footage of the Grand Portage and Pigeon River area in northern Minnesota, the stockade at Grand Portage National Monument, and Ojibwe people filmed by Elmer Albinson. Some of the footage may have been used in Albinson's film My Chippewa Home Revisited.

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/sv000171.xml

Auger, Donald J., and Paul Driben, eds. Grand Portage Chippewa: Stories and Experiences of Grand Portage Band Members. Grand Portage, MN: Grand Portage Tribal Council, 2000.

P851

Peter Pond papers, 1773–1777

Manuscript Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

Description: Two versions of Pond's narrative of his early life as a fur trader and soldier in the "Northwest" and along the St. Peters (Minnesota) River; fur trade accounts used at Grand Portage, 1773-1775, by Pond and his partner, Felix Graham; and a list of supplies to be used by Pond and Greves at Grand Portage (1775).

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/p0851.xml

Secondary

Andrews, Frances. “Grand Portage.” Outdoor America, March 1939.

Cochrane, Timothy. Gichi Bitobag, Grand Marais: Early Accounts of the Anishinaabeg and the North Shore Fur Trade. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2018.