Topics

Category

Era

Grand Portage National Monument

The Grand Portage National Monument in far northeastern Minnesota was established in 1960, after the Grand Portage Band of Lake Superior Chippewa (Ojibwe) ceded nearly 710 acres of their land to the US government. A unit of the National Park Service (NPS), it consists of the eight-and-a-half-mile Grand Portage trail and two trading depot sites—one on the shoreline of Lake Superior and one inland, at Pigeon River. A partially reconstructed depot sits at the Lake Superior site.

The Grand Portage is an ancient overland trail used by Indigenous peoples since at least the start of the first millennium CE. By the middle of the eighteenth century, European fur traders used it and depots at either end to transport people, supplies, and trade goods between the Great Lakes and inland waterways. They abandoned the area in the early nineteenth century. Ojibwe people, however, continued to reside on and near the Grand Portage reservation, which was formed after the ratification of the Treaty of La Pointe in 1854.

The site was largely forgotten by white Minnesotans until the 1920s, when interest in Northwoods history, conservation, and tourism grew rapidly. In 1922, Minnesota Historical Society (MNHS) director Solon Buck launched a campaign to preserve the Grand Portage as a state park. In response to a Grand Portage resident who was worried that private property owners were fencing off the trail, Buck sent MNHS field secretary Cecil Shirk and journalist Paul Bliss to retrace it. The subsequent newspaper coverage generated public interest and support. Because the area was tribal land, however, it fell under federal regulation, and a state park was not possible.

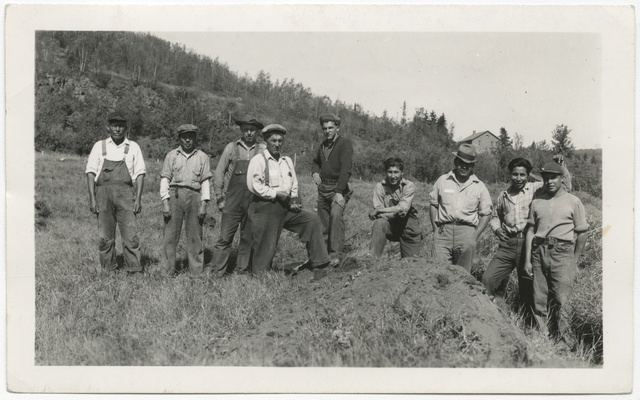

Efforts to preserve and interpret the Grand Portage received federal backing in the 1930s. From 1933 to 1940, archaeologists, historians, and crews from the Indian Division of the Civilian Conservation Corps cleared the trail and conducted archeological digs. They then reconstructed a Great Hall and stockade at the Lake Superior depot site. In 1936, as a result of this work, the federal government declared the Grand Portage a site of national significance.

That same decade, the Grand Portage Band formed a Reservation Tribal Council, as a result of the Indian Reorganization Act in 1934. After World War II, the council joined with white conservationists to urge the federal government to help bring more tourists to the site. Toward that end, the Department of the Interior designated Grand Portage a National Historic Site in 1951. In 1958, the tribal council took the unusual step of ceding 709.97 acres of tribal land to the US government. This allowed the NPS to establish the Grand Portage National Monument two years later.

The creation of the monument sparked a second round of archeological studies and reconstructions. Information from these excavations helped builders design more historically accurate reconstructions. In 1966, for instance, the stockade was rebuilt with a more historically accurate gatehouse.

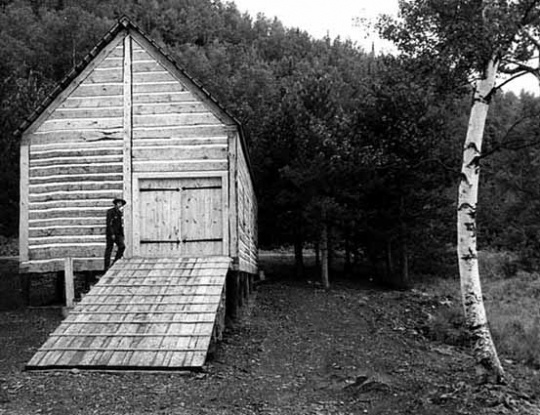

In 1969, lightning struck the Great Hall, starting a fire that destroyed the building and its artifacts. Excavations beneath the rubble revealed information incorporated into a new Great Hall, completed in 1974. A kitchen building found behind the Great Hall was built a year later. A canoe warehouse was built outside the stockade in 1973.

Despite the early involvement of the tribal council, interpretation at the site was largely focused on European fur traders. Slowly, interpretation at the site shifted to include more Ojibwe community histories. One of the most popular yearly events at the monument, Rendezvous Days, began in 1962. This event is a reenactment of the period during midsummer when fur traders, voyageurs, and Indigenous people convened at Grand Portage to exchange furs and supplies. By 1972, Rendezvous Days coincided with what would become the band’s annual Celebration Pow Wow. In 1992, an “Ojibwe village” was reconstructed outside the stockade walls to interpret seasonal cultural practices of Ojibwe people.

In the 1990s, the tribal council advocated for a greater role in site management, and in 1999, the Grand Portage Band and the NPS agreed to co-manage the monument. Together, they moved forward on the construction of a new visitor center, opened in 2007. Known as the Heritage Center, the new building provided more room for interpretative materials, created additional job opportunities for band members, and moved the monument’s offices from Grand Marais to Grand Portage.

Bibliography

Birk, Douglas. “Grand Portage National Monument." National Register of Historic Places nomination form, March 2, 2005.

https://npgallery.nps.gov/AssetDetail/NRIS/66000111

Buck, Solon J. “The Story of the Grand Portage.” Minnesota History 5, no.1 (March 1923):14–27.

http://collections.mnhs.org/mnhistorymagazine/articles/5/v05i01p014-027.pdf

Cockrell, Ron. Grand Portage National Monument, Minnesota: An Administrative History. Omaha, NE: National Park Service Midwest Regional Office, Office of Planning and Resource Preservation Division of Cultural Resources Management. September 1982, rev. October 1983.

http://npshistory.com/publications/grpo/adhi/index.htm

Gilman, Carolyn. The Grand Portage Story. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1992.

Gower, Calvin W. “The CCC Indian Division: Aid for Depressed Americans, 1933–1942.” Minnesota History 43, no.1 (Spring 1972): 3–13.

http://collections.mnhs.org/MNHistoryMagazine/articles/43/v43i01p003-013.pdf

Neil, Pam, and Mike Plummer-Steen. “A Monumental Task: Grand Portage National Monument Celebrates 50 Years.” In The Grand Portage Guide (National Park Service, 2008), 7–19. http://npshistory.com/publications/grpo/newsletter/2008.pdf

Treuer, David. The Heartbeat of Wounded Knee: Native America from 1890 to the Present. New York: Riverhead Books, 2019.

Related Resources

Primary

Bliss, Paul. “Back Two Centuries Over Minnesota’s Oldest Highway to Oldest Fort.” Minneapolis Journal, July 16, 1922.

Busch, Thomas P. “Grand Portage National Monument.” National Register of Historic Places nomination form, April 22, 1976.

https://npgallery.nps.gov/AssetDetail/NRIS/66000111

Fridley, Russel W. “Preserving and Interpreting Minnesota’s Historic Sites.” Minnesota History 37, no.2 (June 1960): 58–70.

http://collections.mnhs.org/MNHistoryMagazine/articles/37/v37i02p058-070.pdf

Schwarz, George M. “The Topography and Geology of the Grand Portage.” Minnesota History 9, no. 1 (March 1928): 26-30.

http://collections.mnhs.org/MNHistoryMagazine/articles/9/v09i01p026-030.pdf

US Department of the Interior. Long-Range Interpretive Plan, Grand Portage National Monument. Harpers Ferry, WV: Harpers Ferry Center, Interpretive Planning, National Park Service.

Secondary

Cochrane, Timothy. Gichi Bitobig, Grand Marais: Early Accounts of the Anishinaabeg and the North Shore Fur Trade. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2018.

Drouillard, Staci Lola. Walking the Old Road: A People’s History of Chippewa City and the Grand Marais Anishinaabe. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2019.

Nute, Grace Lee. The Voyageur’s Highway. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1941, repr. 2002.

Woolworth, Alan R. and Nancy Woolworth. Grand Portage National Monument: An Historical Overview and An Inventory of its Cultural Resources. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1982.

Web

National Park Service. “Grand Portage National Monument.” February 1, 2021. https://www.nps.gov/grpo/index.htm

Visit Cook County, MN. “Grand Portage National Monument, 2016.” YouTube video. August 9, 2016.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FnV46KdD--A

Related Images

Bird’s-eye view of the reconstructed Grand Lodge on Grand Portage Bay

Public domain

More Information

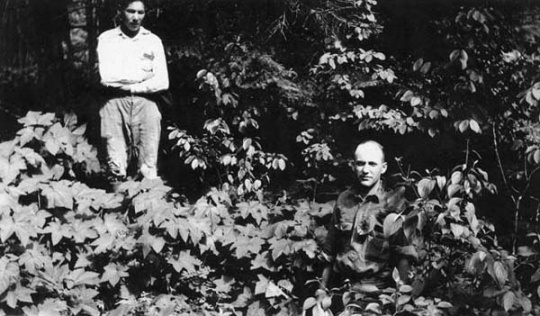

Cecil W. Shirk and Paul LaGarde at the site of Fort Charlotte

Holding Location

More Information

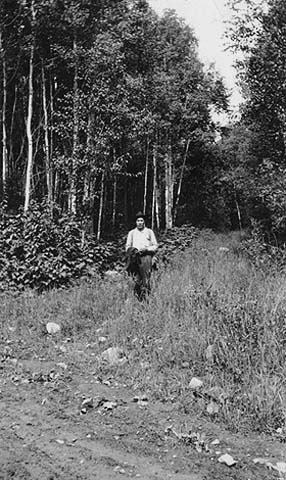

Ojibwe man on Grand Portage trail

Holding Location

More Information

Civilian Conservation Corps workers at Grand Portage

Holding Location

More Information

Dedication of Grand Portage National Historic Site

Holding Location

More Information

Sign at Grand Portage trailhead

All rights reserved

Holding Location

Site of Fort Charlotte on the Pigeon River

Holding Location

More Information

Grand Portage excavation site

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

Excavation work at Grand Portage

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

Reconstructing the Great Hall at Grand Portage

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

Ed Wilson and Mike Flatt at the dedication of Grand Portage as a National Historic Site

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

Grand Portage National Historic Site dedication

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

Restored stockade at Grand Portage

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

Great Hall, Grand Portage National Monument

Holding Location

More Information

Canoe in the Stockade Museum at Grand Portage

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

Great Hall at Grand Portage

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

Canoe shed at Grand Portage

Holding Location

Articles

The Great Hall and kitchen at Grand Portage National Monument

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

Interior of the Grand Portage National Monument Heritage Center

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

Interior of the canoe warehouse at Grand Portage

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

Interior of the Great Hall at Grand Portage

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

Related Articles

Turning Point

In 1958, the Grand Portage Reservation Tribal Council cedes 709.97 acres of Ojibwe tribal land to the US government. This allows the National Park Service to establish the Grand Portage National Monument two years later.

Chronology

1922

1931

1936

1933–1940

1951

1958

1960

1962

1966

1969

1973–1978

1977

1999

2007

Bibliography

Birk, Douglas. “Grand Portage National Monument." National Register of Historic Places nomination form, March 2, 2005.

https://npgallery.nps.gov/AssetDetail/NRIS/66000111

Buck, Solon J. “The Story of the Grand Portage.” Minnesota History 5, no.1 (March 1923):14–27.

http://collections.mnhs.org/mnhistorymagazine/articles/5/v05i01p014-027.pdf

Cockrell, Ron. Grand Portage National Monument, Minnesota: An Administrative History. Omaha, NE: National Park Service Midwest Regional Office, Office of Planning and Resource Preservation Division of Cultural Resources Management. September 1982, rev. October 1983.

http://npshistory.com/publications/grpo/adhi/index.htm

Gilman, Carolyn. The Grand Portage Story. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1992.

Gower, Calvin W. “The CCC Indian Division: Aid for Depressed Americans, 1933–1942.” Minnesota History 43, no.1 (Spring 1972): 3–13.

http://collections.mnhs.org/MNHistoryMagazine/articles/43/v43i01p003-013.pdf

Neil, Pam, and Mike Plummer-Steen. “A Monumental Task: Grand Portage National Monument Celebrates 50 Years.” In The Grand Portage Guide (National Park Service, 2008), 7–19. http://npshistory.com/publications/grpo/newsletter/2008.pdf

Treuer, David. The Heartbeat of Wounded Knee: Native America from 1890 to the Present. New York: Riverhead Books, 2019.

Related Resources

Primary

Bliss, Paul. “Back Two Centuries Over Minnesota’s Oldest Highway to Oldest Fort.” Minneapolis Journal, July 16, 1922.

Busch, Thomas P. “Grand Portage National Monument.” National Register of Historic Places nomination form, April 22, 1976.

https://npgallery.nps.gov/AssetDetail/NRIS/66000111

Fridley, Russel W. “Preserving and Interpreting Minnesota’s Historic Sites.” Minnesota History 37, no.2 (June 1960): 58–70.

http://collections.mnhs.org/MNHistoryMagazine/articles/37/v37i02p058-070.pdf

Schwarz, George M. “The Topography and Geology of the Grand Portage.” Minnesota History 9, no. 1 (March 1928): 26-30.

http://collections.mnhs.org/MNHistoryMagazine/articles/9/v09i01p026-030.pdf

US Department of the Interior. Long-Range Interpretive Plan, Grand Portage National Monument. Harpers Ferry, WV: Harpers Ferry Center, Interpretive Planning, National Park Service.

Secondary

Cochrane, Timothy. Gichi Bitobig, Grand Marais: Early Accounts of the Anishinaabeg and the North Shore Fur Trade. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2018.

Drouillard, Staci Lola. Walking the Old Road: A People’s History of Chippewa City and the Grand Marais Anishinaabe. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2019.

Nute, Grace Lee. The Voyageur’s Highway. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1941, repr. 2002.

Woolworth, Alan R. and Nancy Woolworth. Grand Portage National Monument: An Historical Overview and An Inventory of its Cultural Resources. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1982.

Web

National Park Service. “Grand Portage National Monument.” February 1, 2021. https://www.nps.gov/grpo/index.htm

Visit Cook County, MN. “Grand Portage National Monument, 2016.” YouTube video. August 9, 2016.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FnV46KdD--A