Although long ignored in Underground Railroad scholarship, evidence indicates that small groups of Black and white abolitionists in Minnesota aided freedom seekers at different times and places in the 1850s and 60s. Waterways like the Mississippi River and territorial-era stagecoach roads were integral to the freedom movement. Free Black barbers, steamboat workers, and businessmen in Minnesota cooperated with abolitionists in Galena, Chicago, St. Louis, and beyond, all with a common goal: the end of slavery.

As they do in other states, legends, inconsistencies, and a system of operation meant to be elusive complicate a full understanding of the Underground Railroad in Minnesota. While slavery was technically illegal there, boundaries between freedom and bondage were blurry. Southern businessmen and Fort Snelling officers often brought enslaved individuals in and out of Minnesota from slave states. The Dred Scott case famously examined the complexity of this issue in court.

Following the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850, crossing the invisible boundary into the North was not enough to guarantee one's safety and freedom. Freedom seekers could still be captured and brought back to the South. In response, many self-emancipated individuals traveled deeper into the wilderness of the upper Midwest and away from the detection of slave catchers. While some continued on into Canada, others settled into the region’s growing boomtowns or mining and farming communities. Free Blacks also began moving to the region in search of opportunities for advancement and freedom from the oppression of Black codes enacted in other states.

Minnesota Territory, then at the edge of westward growth, was an ideal destination for freedom seekers. Free Blacks found opportunities for work and community building in the area’s booming river towns. Goods and people circulated on steamboats and stagecoach lines, and the individuals who gathered in spaces like barbershops and eating saloons found opportunities to use those existing paths and industries to lead people to freedom.

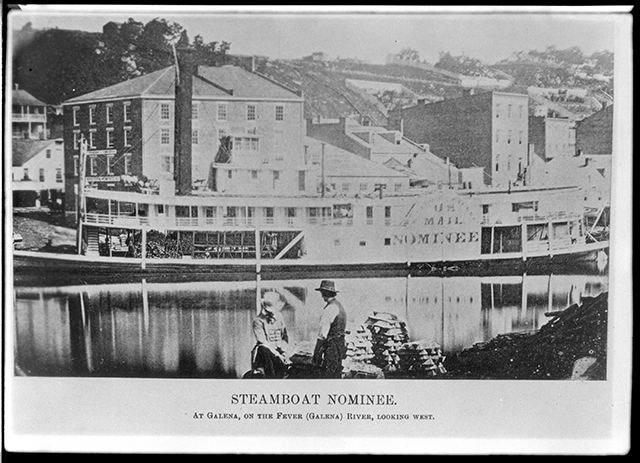

In 1850, around the same time as the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act, a number of free Black abolitionists began settling in the territorial city of St. Paul from Galena, Illinois. Many worked on steamboats like the Dr. Franklin, Oronoco, and Nominee as barbers, porters, and laborers, moving up and down the river from New Orleans to St. Paul. Black barbers in particular were known to be integral to the freedom movement in other parts of the country for their roles in information sharing and gathering, and building networks. Many known Underground Railroad agents were barbers.

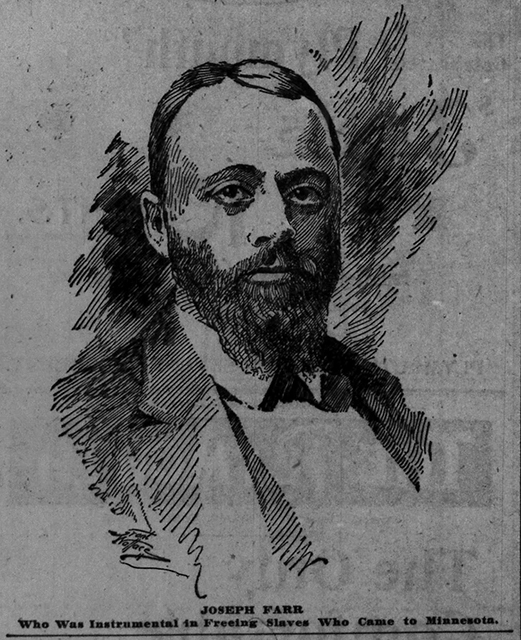

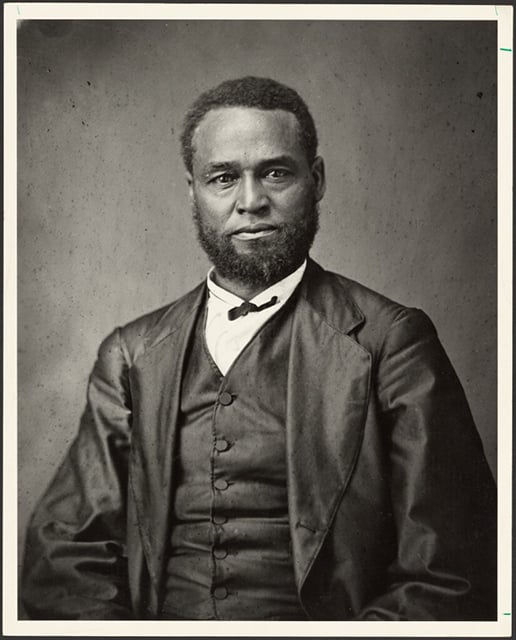

Joseph Farr and his uncle William Taylor aided in the Underground Railroad in the 1850s after moving to St. Paul from Galena. Taylor’s barber shop on Third Street (now Kellogg) placed them in sight of incoming steamboats on the Mississippi River. Others involved in helping people to freedom in the city included a man named David Edwards [Talbert], who worked as a cook at International Hotel; steamboat worker Eugene Berry; an agent in Galena named James Garrett Johnson; and fellow barber James Highwarden. Berry and others working on the steamboats further down river disguised fugitive slaves, including women, as young male laborers on board. Once in St. Paul, they hid escapees at Taylor’s home across Third, or at an ice cream saloon a few blocks away. A white ally named Fournier who lived near White Bear Lake aided in the effort, as did stagecoach operator and future St. Anthony mayor Alvaren Allen, and unnamed allies in Prescott, Wisconsin, across the river from Hastings.

Black abolitionist Moses Dickson, recognized nationally as a leader in the Underground Railroad, lived in St. Paul during the years leading up to statehood. Dickson lived near Farr and Taylor in Galena before moving north, and he had close connections to known UGRR operators in Galena and Saint Louis. James Garrett Johnson, whom Farr mentions as an agent in his own recollection, was a member of the International Order of Twelve in Galena, one of two secret abolitionist organizations Dickson started. In St. Paul, Dickson and his wife Mary operated an eating saloon and later a barbershop, both possibly aiding in his abolitionist efforts. Dickson was also the first educator of African American children in town.

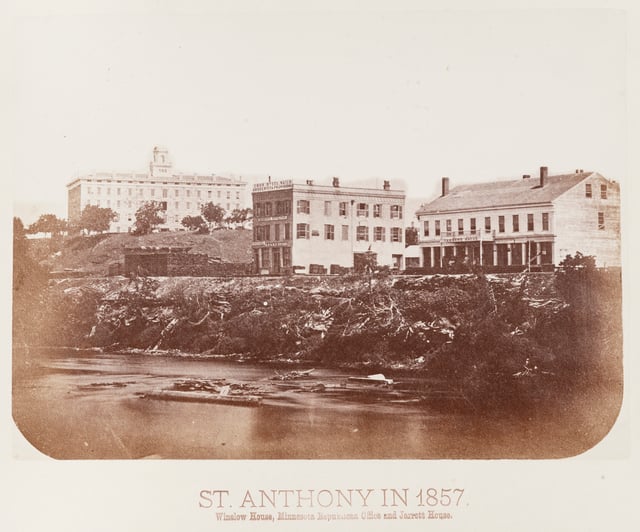

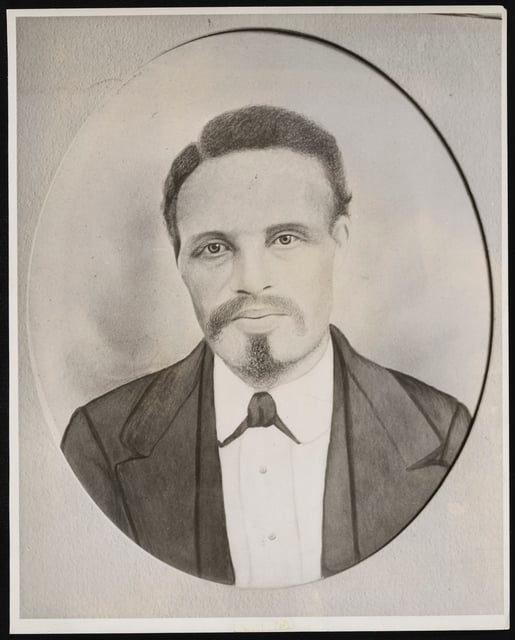

By the late 1850s, more abolitionist-minded individuals began moving to the region from New England. Among them were Ralph and Emily Grey, a free Black couple from York, Pennsylvania. The couple settled in Saint Anthony where Ralph ran a barber shop. In 1860, the Greys famously helped Eliza Winston in her freedom case and subsequent escape to freedom. Winston and her husband had partially paid for their freedom from the Gholson family years earlier, but Eliza was still sold to the Christmas family.

When Eliza was brought North with the family from Mississippi the Greys helped her arrange a hearing. Although a Minnesota judge ruled in her favor, a pro-slavery mob converged on her location to return her to slavery. The Greys reportedly aided Eliza in an escape to Canada, although reports conflict about her eventual whereabouts. Emily’s father William Goodridge was a noted Underground Railroad leader in York, and joined them in Minnesota by the mid-1860s. Minneapolis Pioneers and Soldiers Memorial Cemetery, where the Grey and Goodridge family are buried, was recently awarded Network to Freedom designation for the burial site's connection to freedom seeking history.

Minnesota remained an active place of freedom seeking even up through the end of the Civil War. Following the Emancipation Proclamation, a group of formerly enslaved individuals in Missouri headed up river on the steamboat Northerner in search of freedom and a new life. The group of 125 refugees, including their leader Rev. Robert Hickman, founded Pilgrim Baptist Church in the years following the war. In 2023 the church and freedom seekers became the first Minnesota location designated on the National Park Service’s Network to Freedom map.

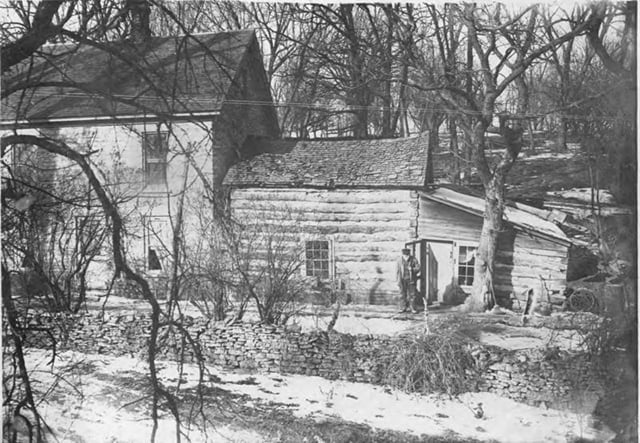

In addition to the above stories, there are also numerous individuals from Minnesota’s past that are being explored as possible but unverified agents and operators. In Southeast Minnesota, numerous rumored locations exist around Rushford, like the Rosewell Valentine House. Daniel Dayton, owner of a stagecoach stop in Big Springs along the Dubuque-St. Paul Trail, is considered by some to be a possible agent given his abolitionist beliefs, industry, and location.

Another hint of the Underground Railroad in the southeast part of the state is the Jeffrey family, who settled in Hart, north of Rushford. The free Black family has abolitionist roots in maritime Connecticut. From the 1840s through the 1860s, clusters of their family began settling around the upper Midwest, including Hart, the Twin Cities, Chicago, and Upper Peninsula Michigan.

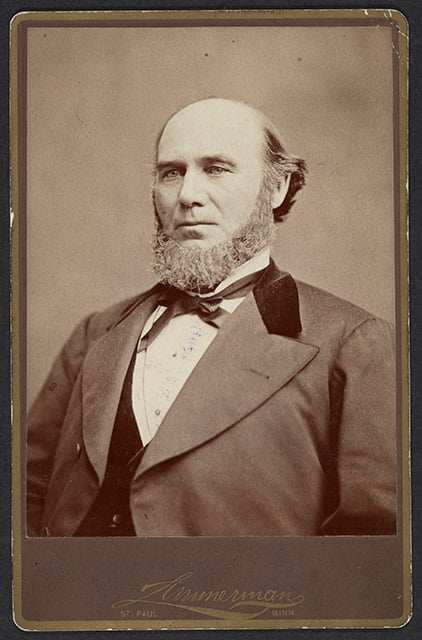

In Winona, steamboat Captain Orrin Smith may also have aided in the transportation of escaped slaves. Many in St. Paul and Galena’s Black freedom networks worked on boats owned by Smith over the years. Winona’s large abolitionist community at the First Congregationalist Church may also have contained individuals helping in the effort, as did Winona’s Black barbers. There is evidence that abolitionists active in the UGRR in other regions of the country later settled in Minnesota. Among them was Oren Birney Cravath, reportedly an agent in Ohio and New York, who settled in St. Charles in Winona County.

Despite evidence of numerous abolitionists living in the southeast part of the state, and the region’s existing territorial transportation networks, no verified accounts from freedom seekers or agents have yet been discovered. Historians across the state continue to seek documentation that helps better understand these networks.

Editor’s note: The claim that Farr, Taylor, Edwards, Berry, Johnson, and white allies operated an Underground Railroad network in Minnesota appears in a reminiscence written by Farr and printed in the St. Paul Pioneer Press in 1895, half a century after the events described. No other surviving source confirms this information. Farr’s story of dressing up a girl as a boy was a common one shared in Underground Railroad recollections nationwide. Moses Dickson, in fact, shares a nearly identical story in his own end-of-life memoir, but he claims the incident occurred in New Orleans. Dickson’s account also states that he was organizing a slave rebellion in the Deep South in the 1850s—even though records place him in St. Paul or Galena for most of the decade. Dickson’s account does mention being in Wisconsin Territory (which included Minnesota) in the 1840s, but it neglects to mention his time in St. Paul as a barber, business owner, and educator. As with the stories of Farr and Taylor, no additional evidence confirms Dickson’s account of helping freedom seekers beyond a half-century-old recollection. Paper trails conflict with both men’s stories.