On March 24, 1857, abolitionist and St. Paul resident Moses Dickson wrote a scathing open letter to the Minnesota Weekly Times about freedom, democracy, and citizenship for Black Americans. Although it was addressed to a land agent named T. M. Fullerton, the letter appealed to all white Minnesotans to recognize the humanity of their Black neighbors. It provides a record of one man’s response to racial inequality in Minnesota (and across the US) in the 1850s.

After the US Supreme Court took up the case of Dred Scott v. Sandford in February of 1856, it considered whether the US Constitution included Black people in its definition of citizens. The ongoing argument left many free African Americans living in Minnesota questioning their legal status. Although the Black codes that governed southern states at the time did not exist in Minnesota Territory, political leaders had found other ways to limit the freedoms of free Blacks moving to northern states.

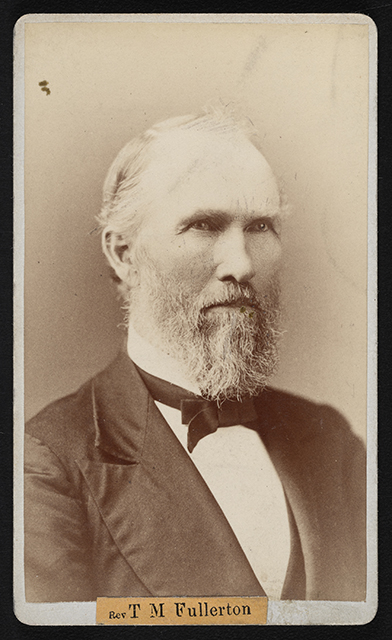

The national question of Black land ownership sparked local debates as Minnesota Territory readied for statehood. In late 1856, a letter-writer to the Minnesota Weekly Times presented a question to the newspaper: Did the Pre-Emption Act of 1841, which allowed US citizens to claim federal land, apply to African Americans in Minnesota? The paper’s editor passed on his query to Stillwater land agent T. M. Fullerton and published his answer on January 3, 1857.

In his reply, Fullerton dismissed the land claims of African Americans by denying their citizenship. He wrote that “Colored persons are not, by any of the United States laws, regarded as citizens[.]” When the Supreme Court issued its ruling in Scott v. Sandford two months later, it agreed with him, and Fullerton celebrated the decision in a letter to the Daily Pioneer and Democrat.

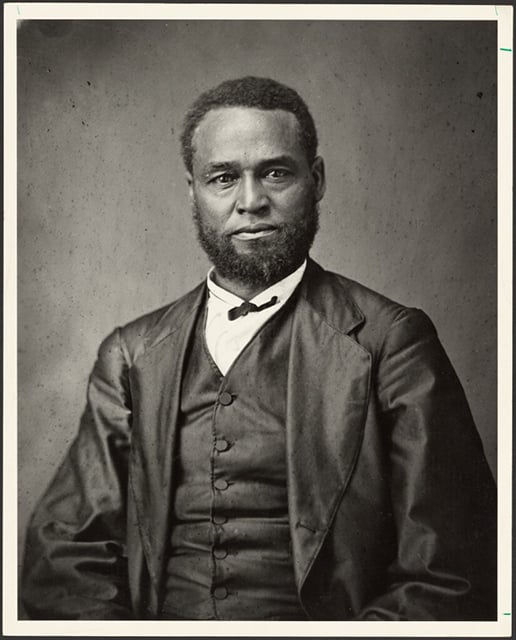

Black abolitionist and possible Underground Railroad agent Moses Dickson, who was also a business owner in St. Paul, read both of Fullerton’s letters. He responded via the Minnesota Weekly Times in a letter of his own published on March 28. He noted the irony of Fullerton’s training as a preacher and the fact that five of the Supreme Court justices were current or former slaveholders. After asking if Fullerton had ever read the Declaration of Independence, Dickson continued:

Why do you make merry over this piece of Judicial Tyranny? In what have I offended that this injustice should be heaped upon me and mine? Is it because I love my country less than you?—No! for you have all the advantages of education and refinement that society can furnish, and are eligible to any office at the gift of the People, your affection for your native land is only enough to put her in chains; while I, though depressed and downtrodden by my country ever since I saw the light of day, love her still….

What kind of institution is a negro? Who am I? I am not an alien, for I was born on American soil. I am not a citizen, for you and your subordinates, the five slaveholders, say I am not. I am a thing. I live, breathe, eat, work, think, die, and if I have a soul—does it go before the eternal judge? Or does the Supreme Court take care of that, too? I may acquire property, but the United States refuses to protect it. I cannot sue for injuries done me, or money due me. There is only one palliating circumstance in this chapter of hellish law—I cannot commit treason as there is no nation to which I owe allegiance. I cannot longer love my country for I have no country to love!

Dickson closed the letter by saying that although he expected Fullerton to ignore him in public after he read his words, the reverend could at least remember him in his private prayers.

No written response from Fullerton to Dickson survives. Fullerton ended his role as land agent later that year and returned to preaching. Dickson moved downriver to Missouri and entered the ministry himself. Free Blacks who continued to live in Minnesota in the late 1850s and early 1860s did so without protection under the law, and without the same rights as white settlers, until 1868. In that year, a state amendment granted suffrage to all non-white men.

Editor’s note: To read all of Dickson’s letter in a more accessible size than the original, see the citation in the bibliography below.