Topics

Category

Era

Gooseberry Falls State Park

One of Minnesota’s most popular nature areas, Gooseberry Falls was the first of eight state parks developed along Lake Superior’s North Shore. Nearly all of its buildings were constructed by employees of the Civilian Conservation Corps between 1934 and 1941. The collection of stone and log structures presents a distinctively North Shore interpretation of the National Park Service’s Rustic Style of architecture, complementing the park’s river, waterfalls, woodlands, and lakeshore.

The dark, fine-textured basalt rock that characterizes the North Shore of Lake Superior was deposited 1.1 billion years ago as volcanic lava flow. Ice Age glaciers, along with wind, water, and the weight of the lava itself, created a depression that became the cliffs and bed of Lake Superior. The last of the glaciers etched into the basalt to define the course of the Gooseberry River and its waterfalls.

An enduring controversy surrounds the name of the Gooseberry River. Some say Ojibwe people named it Shabonimikani-zibi (Place of the Gooseberries) for the gooseberries that grew nearby. Others claim it was named Riviere des Groseilliers to honor Frenchman Medard Chouart, Sieur Des Groseilliers, who explored Lake Superior’s North Shore in 1659–1660 with his brother-in-law, Pierre-Esprit Radisson. (Groseille translates to gooseberry or currant.) The French explanation carries the weight of written history, since the river was labeled with Des Groseilliers’s name on the earliest French map of the area in the late 1600s, some fifty years before the Ojibwe were known to have lived on the North Shore. It is possible, though, that the Ojibwe hunted and fished in the area while completing their migration from North America’s East Coast.

Throughout the peak fur trading years (ca. 1679–1847), transportation, commerce, and development largely bypassed the Gooseberry River. In the late nineteenth century, trout fishing was popular in the rivers along the lakeshore, and logging companies started to move into the Gooseberry River area. In 1899 Wisconsin timberland speculators William F. Vilas and John C. Knight purchased a 30,000-acre tract of land, including the Gooseberry River watershed, and leased it to Thomas Nestor of Ashland, Wisconsin. Nestor clear cut the trees, rafting logs across Lake Superior to mills in Wisconsin and Michigan. By the time Nestor’s lease expired in 1909, both Vilas and Knight had died, leaving the property to Vilas’s estate.

With the growing popularity of automobiles and tourism during the 1910s and 1920s, adventurous Minnesotans took to the state’s rough, narrow roads to explore the North Shore. In 1925, the Minnesota Department of Highways completed two major projects that drew even greater tourism to Gooseberry Falls. One was rerouting Trunk Highway 1 (later designated Trunk Highway 61), bringing the still-unpaved roadway out from the backwoods to provide visitors with panoramic views of Lake Superior. The second project was the construction of a bridge over the Gooseberry River.

The increase of automobile traffic led businessmen from nearby Two Harbors to propose that the Minnesota Legislature purchase 640 acres from the Vilas estate. They envisioned a park encompassing the river’s five waterfalls and extending to the lakeshore. The legislature approved the site as a game refuge in 1933, to be managed jointly by the Department of Highways and the Department of Conservation. In a Depression-era economy, no funds were appropriated for development.

A year later, however, the federal government created the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). Administered by the National Park Service (NPS), the CCC was charged with developing an infrastructure of roads, trails, and buildings at the Gooseberry Falls site. Under the NPS’s authority, all major structures were designed in the Rustic Style (sometimes called Parkitecture), reflecting the natural features of a park’s vicinity. At Gooseberry Falls, that meant using local stone and timber, providing a uniquely colorful construction palette. CCC workers quarried red granite near Duluth’s College of St. Scholastica. Blue, brown, and black granite came from East Beaver Bay, north of the park. Sand was brought in from Flood Bay near Two Harbors, and logs were hauled from Cascade River State Park, fifty-five miles north.

Workers built more than eighty structures and facilities for the park, including a water tower, shelters, cabins, stone steps, fireplaces, and drinking fountains. The most impressive structure was the Stone Concourse, known as Castle in the Park, a 300-foot retaining wall which provided parking and a viewing area.

The park, which now comprises 1,662 acres, offers hiking, camping, picnicking, and lakefront access, but the main attraction continues to be the park’s five waterfalls. Gooseberry Falls is designated as one of the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources’ sixteen “destination parks,” offering modern facilities and naturalist-led interpretive programs, designed for heavy use and attracting visitors from throughout the state. Eighty-eight of the park’s CCC/rustic-style structures were listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1989.

Bibliography

Anderson, Rolf T. “Gooseberry Falls State Park, CCC Rustic Style Historic Resources.” National Register of Historic Places nomination form, September 1989. State Historic Preservation Office, St. Paul.

https://catalog.archives.gov/id/93200557

Benson, David R. Stories in Log and Stone: The Legacy of the New Deal in Minnesota State Parks. St. Paul: State of Minnesota, Department of Natural Resources, Division of Parks and Recreation, 2002.

Conradi, Linda. “Gooseberry Falls.” Zenith City Online, undated.

Dierckins, Tony. Duluth: An Urban Biography. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2020.

Heilbron, Bertha L. “The State Historical Convention of 1938.” Minnesota History 19, no. 4 (1938): 308–317.

http://collections.mnhs.org/mnhistorymagazine/articles/19/v19i03p308-317.pdf

LeMay, Konnie. “Rockin’ the Rift, the Billion-Year-Old Spit that Made Us.” Lake Superior, July 30, 2018.

https://www.lakesuperior.com/the-lake/402rockin-the-rift-the-billion-year-old-split-that-made-us

Long, Barbara Beving, Historian. “Bridge No. 3585, Gooseberry Falls State Park: Spanning Gooseberry River at Trunk Highway 61.” Historic American Engineering Record, Rocky Mountain Regional Office, National Park Service, Denver, Colorado, March 1996.

http://lcweb2.loc.gov/master/pnp/habshaer/mn/mn0500/mn0547/data/mn0547data.pdf

Miller, James D., Mark A. Jirsa, and Phillip Leversedge. “Lake Superior—Born of Fire and Ice.” Geology of Minnesota Parks. Minnesota Geological Survey, 2000.

https://conservancy.umn.edu/bitstream/handle/11299/93850/24-Tetteguche.pdf

[Minnesota Department of Natural Resources]. “Development and Acquisition Status: Gooseberry Falls State Park,” October 26, 1989.

https://www.leg.mn.gov/docs/pre2003/other/900251/Volume19.pdf

“MNDOT Historic Roadside Development Structures Inventory: Gooseberry Falls Concourse.” Historic Roadside Development Structures on Minnesota Trunk Highways, 1998.

http://www.dot.state.mn.us/roadsides/historic/files/iforms/LA-SVC-046.pdf

Nute, Grace Lee. The Voyageur’s Highway. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2002 (reprint).

Radzak, Lee. The View From Split Rock: A Lighthouse Keeper’s Life. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 2021.

Schwartz, G. M. “The Geology of Gooseberry State Park.” Geology of Minnesota Parks 4 . Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, 1948.

https://conservancy.umn.edu/bitstream/handle/11299/93600/04-Gooseberry.pdf

Smith, Doug. “Face Lift for the Falls.” Minneapolis Star Tribune, July 14, 1996.

Sommer, Barbara W. Hard Work and a Good Deal: The Civilian Conservation Corps in Minnesota. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2008.

System Plan: Charting a Course for the Future. Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, Division of Parks and Trails, February 2019.

https://files.dnr.state.mn.us/input/mgmtplans/pat/system_plan/system_plan.pdf

Related Resources

Primary

Photographs of State Parks, Monuments, Recreational Areas, and Staff, 1926–1956 (bulk 1930–1939)

Minnesota Department of Conservation

State Archives Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

Description: The collection includes seven folders of of photographs of Gooseberry Park buildings under construction and completed, including the refectory (1945), stonework used in the walls and facilities, the picnic and beach area (1936), the upper and lower falls, tree planting (1935), scenic views, and recreational activities, including logrolling, baseball, and tobogganing.

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/gr01426.xml

Secondary

Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. "A Management Plan for Gooseberry Falls State Park." November 1979.

https://www.lrl.mn.gov/docs/pre2003/other/811355.pdf

Nute, Grace Lee. “Gooseberry Falls State Park,” Part 1. Minnesota Conservation Volunteer 10 (May–June 1947), 27–30. https://apps.dnr.state.mn.us/volunteer_index/api/v1/article_pdf?id=4477

——— . “Gooseberry Falls State Park,” Part 2. Minnesota Conservation Volunteer 11 (July–August 1947), 7–11. https://apps.dnr.state.mn.us/volunteer_index/api/v1/article_pdf?id=4611

[National Park Service]. “Souvenir of Co. 2710-C.C.C.: Gooseberry Falls State Park, April 26–27, 1941.”

Stein, Seth, Carol A. Stein, Eunice Blavascunas, and Jonas Kley. “Using Lake Superior Parks to Explain the Midcontinent Rift.” National Park Service, Summer 2015.

https://www.nps.gov/articles/parkscience32_1_19-29_stein_et_al_3817.htm

Tweed, William C., Laura E. Soulliere, and Henry G. Law. National Park Service Rustic Architecture: 1916-1942. [N.p.]: National Park Service, 1977.

https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/rusticarch/introduction.htm

Web

Gooseberry Falls State Park. https://npgallery.nps.gov/GetAsset/8c99ed0d-7960-4c56-b3ed-edae919068a2#:~:text=Gooseberry%20Falls%20State%20Park%20CCC/Rustlc%20Style%20Historic%20Resources%20are,just%20north%20of%20the%20park.

Gooseberry Falls State Park. Minnesota Department of Natural Resources.

https://www.dnr.state.mn.us/state_parks/park.html?id=spk00172#homepage

Related Images

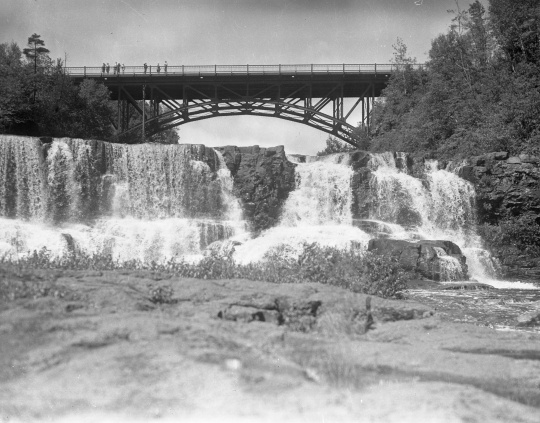

Lower and upper Gooseberry Falls

Holding Location

Articles

Overlook at lower Gooseberry Falls

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

Gooseberry Falls and bridge

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

Cars parked outside Bridgehead Refectory

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

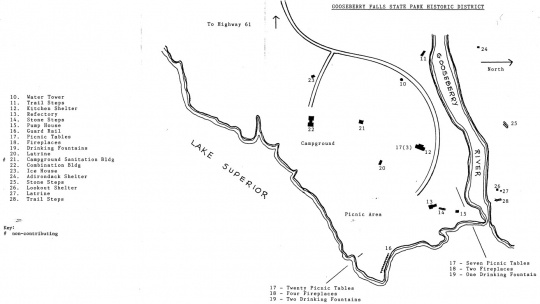

Map of Gooseberry Falls State Park Historic District

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

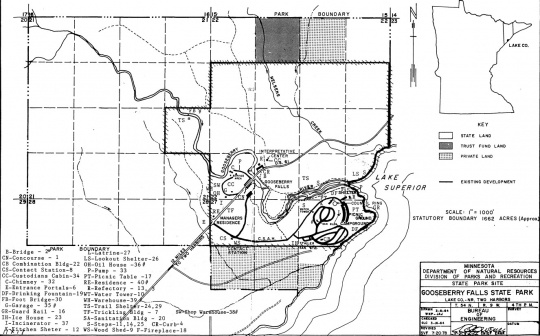

Map of Gooseberry Falls State Park

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

Aerial view of Gooseberry Falls State Park

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

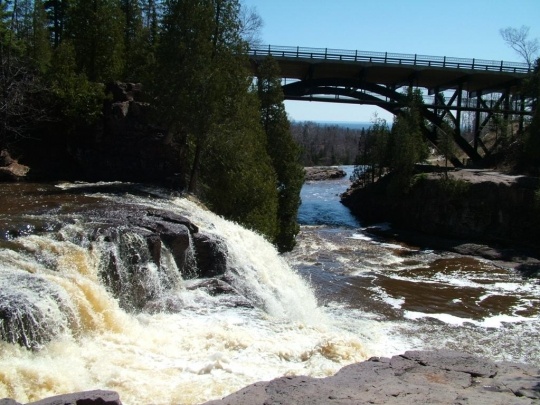

Gooseberry Falls

Gooseberry Falls, April 23, 2005. Photograph by Wikimedia Commons user Aaron Fulkerson. CC BY 2.5

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

Bird’s-eye view of Gooseberry Falls State Park

Holding Location

Articles

.jpeg)

Gooseberry Falls State Park in autumn

Holding Location

View from Gitchi Gummi Trail

Holding Location

Articles

Gooseberry Falls

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

.jpeg)

Agate Beach

Holding Location

Articles

Falls View Shelter (Bridgehead Refectory)

Falls View Shelter, originally used as a visitors’ center for Gooseberry Falls State Park; also known as the Bridgehead Refectory. Photograph by Noah Barton, 2021. Used with the permission of Noah Barton.

All rights reserved

Articles

Fifth Falls Shelter

All rights reserved

Articles

Lady Slipper Lodge

All rights reserved

Articles

Water tower

All rights reserved

Articles

Joseph N. Alexander Visitors’ Center

Holding Location

Articles

Related Articles

Turning Point

In 1933, Two Harbors business owners propose that the area along the Gooseberry River be preserved as a state park. The Minnesota Legislature purchases 640 acres in the Gooseberry River basin and classifies it as a scenic game preserve, protecting the site from private development and making way for its designation as a state park.

Chronology

1600

1659

1825

1825

1890s

1899

1900–1909

1925

1933

1934

1936–1940

1937

1937–1938

1941

1989

1996–1998

Bibliography

Anderson, Rolf T. “Gooseberry Falls State Park, CCC Rustic Style Historic Resources.” National Register of Historic Places nomination form, September 1989. State Historic Preservation Office, St. Paul.

https://catalog.archives.gov/id/93200557

Benson, David R. Stories in Log and Stone: The Legacy of the New Deal in Minnesota State Parks. St. Paul: State of Minnesota, Department of Natural Resources, Division of Parks and Recreation, 2002.

Conradi, Linda. “Gooseberry Falls.” Zenith City Online, undated.

Dierckins, Tony. Duluth: An Urban Biography. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2020.

Heilbron, Bertha L. “The State Historical Convention of 1938.” Minnesota History 19, no. 4 (1938): 308–317.

http://collections.mnhs.org/mnhistorymagazine/articles/19/v19i03p308-317.pdf

LeMay, Konnie. “Rockin’ the Rift, the Billion-Year-Old Spit that Made Us.” Lake Superior, July 30, 2018.

https://www.lakesuperior.com/the-lake/402rockin-the-rift-the-billion-year-old-split-that-made-us

Long, Barbara Beving, Historian. “Bridge No. 3585, Gooseberry Falls State Park: Spanning Gooseberry River at Trunk Highway 61.” Historic American Engineering Record, Rocky Mountain Regional Office, National Park Service, Denver, Colorado, March 1996.

http://lcweb2.loc.gov/master/pnp/habshaer/mn/mn0500/mn0547/data/mn0547data.pdf

Miller, James D., Mark A. Jirsa, and Phillip Leversedge. “Lake Superior—Born of Fire and Ice.” Geology of Minnesota Parks. Minnesota Geological Survey, 2000.

https://conservancy.umn.edu/bitstream/handle/11299/93850/24-Tetteguche.pdf

[Minnesota Department of Natural Resources]. “Development and Acquisition Status: Gooseberry Falls State Park,” October 26, 1989.

https://www.leg.mn.gov/docs/pre2003/other/900251/Volume19.pdf

“MNDOT Historic Roadside Development Structures Inventory: Gooseberry Falls Concourse.” Historic Roadside Development Structures on Minnesota Trunk Highways, 1998.

http://www.dot.state.mn.us/roadsides/historic/files/iforms/LA-SVC-046.pdf

Nute, Grace Lee. The Voyageur’s Highway. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2002 (reprint).

Radzak, Lee. The View From Split Rock: A Lighthouse Keeper’s Life. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 2021.

Schwartz, G. M. “The Geology of Gooseberry State Park.” Geology of Minnesota Parks 4 . Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, 1948.

https://conservancy.umn.edu/bitstream/handle/11299/93600/04-Gooseberry.pdf

Smith, Doug. “Face Lift for the Falls.” Minneapolis Star Tribune, July 14, 1996.

Sommer, Barbara W. Hard Work and a Good Deal: The Civilian Conservation Corps in Minnesota. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2008.

System Plan: Charting a Course for the Future. Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, Division of Parks and Trails, February 2019.

https://files.dnr.state.mn.us/input/mgmtplans/pat/system_plan/system_plan.pdf

Related Resources

Primary

Photographs of State Parks, Monuments, Recreational Areas, and Staff, 1926–1956 (bulk 1930–1939)

Minnesota Department of Conservation

State Archives Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

Description: The collection includes seven folders of of photographs of Gooseberry Park buildings under construction and completed, including the refectory (1945), stonework used in the walls and facilities, the picnic and beach area (1936), the upper and lower falls, tree planting (1935), scenic views, and recreational activities, including logrolling, baseball, and tobogganing.

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/gr01426.xml

Secondary

Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. "A Management Plan for Gooseberry Falls State Park." November 1979.

https://www.lrl.mn.gov/docs/pre2003/other/811355.pdf

Nute, Grace Lee. “Gooseberry Falls State Park,” Part 1. Minnesota Conservation Volunteer 10 (May–June 1947), 27–30. https://apps.dnr.state.mn.us/volunteer_index/api/v1/article_pdf?id=4477

——— . “Gooseberry Falls State Park,” Part 2. Minnesota Conservation Volunteer 11 (July–August 1947), 7–11. https://apps.dnr.state.mn.us/volunteer_index/api/v1/article_pdf?id=4611

[National Park Service]. “Souvenir of Co. 2710-C.C.C.: Gooseberry Falls State Park, April 26–27, 1941.”

Stein, Seth, Carol A. Stein, Eunice Blavascunas, and Jonas Kley. “Using Lake Superior Parks to Explain the Midcontinent Rift.” National Park Service, Summer 2015.

https://www.nps.gov/articles/parkscience32_1_19-29_stein_et_al_3817.htm

Tweed, William C., Laura E. Soulliere, and Henry G. Law. National Park Service Rustic Architecture: 1916-1942. [N.p.]: National Park Service, 1977.

https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/rusticarch/introduction.htm

Web

Gooseberry Falls State Park. https://npgallery.nps.gov/GetAsset/8c99ed0d-7960-4c56-b3ed-edae919068a2#:~:text=Gooseberry%20Falls%20State%20Park%20CCC/Rustlc%20Style%20Historic%20Resources%20are,just%20north%20of%20the%20park.

Gooseberry Falls State Park. Minnesota Department of Natural Resources.

https://www.dnr.state.mn.us/state_parks/park.html?id=spk00172#homepage

.jpeg?width=200&height=200&name=Gooseberry_Falls_State_Park_-_Fall_Colors_(22287367439).jpeg)

.jpeg?width=200&height=200&name=Agate_Beach_(Gooseberry_Falls_State_Park).jpeg)