Topics

Category

Era

Gateway District (“Skid Row”), Minneapolis

The Gateway District was Minneapolis’s original downtown, where life revolved around mills and railroads. As aging buildings became boarding houses for the thousands of temporary workers who spent their off-seasons in Minneapolis, the neighborhood gained a seedy reputation and the nickname “Skid Row.” The twenty-five-block zone was targeted for decades by mission workers, city planners, and police as a hub of vice and firetrap buildings, but the redevelopment of the area failed to mitigate its decline after World War II.

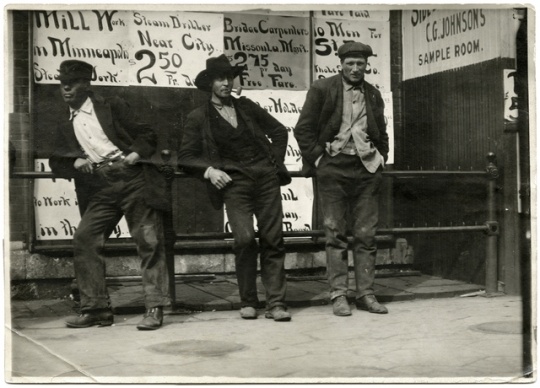

Minneapolis’s transition from town to city was fueled by the Mississippi River and seasonal workers. Lumberjacks floated old-growth timber down the river each spring for milling. In the summer and fall, wheat was brought to the city on tracks built and maintained by railroad workers known as “gandy dancers.” When Minneapolis’s downtown shifted away from the river, dozens of offices and homes between First and Fifth Avenues were converted into inexpensive boarding houses for these workers.

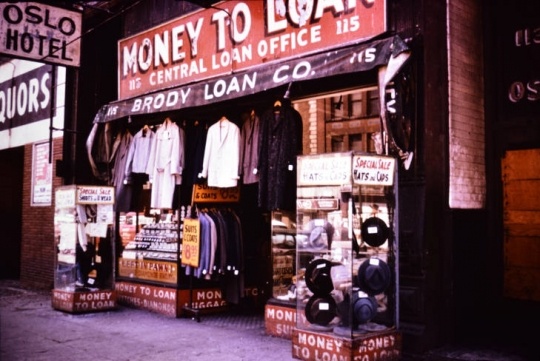

Originally known as Bridge Square, the twenty-five-block area was home to hundreds of small business owners, including grocers, lawyers, and barbers. It was better known, however, as one of the only places in Minneapolis to buy a drink legally for decades. Reasoning that law enforcement would be easier and neighborhoods safer if saloons were confined to one district, the city council passed ordinances in 1884 making it difficult to open a saloon anywhere but in the immigrant neighborhoods along the riverside. Ironically, this turned Minneapolis’s old downtown into a de-facto “vice” district—known as “Skid Row” by the 1920s—where seasonal workers and permanent Minneapolitans alike came for liquor, gambling, and prostitution. By 1902, there were more than 100 saloons on Washington Avenue alone.

By World War I, the neighborhood had transformed from a mixed-income community of immigrant families to one of predominantly young and single transient men who defied “Yankee” attitudes for proper living. In the 1910s, city planners attempted to rebrand Skid Row as the “Gateway” to Minneapolis by razing four blocks of lodging, building a Neoclassical-inspired park, and banning women from boarding houses. In hopes of curbing prostitution, churches and women’s groups built hotels and boarding houses for the single women who worked at downtown hospitals, factories, and private homes. In spite of these efforts and Prohibition, the neighborhood remained an inexpensive haven for Midwestern seasonal workers and Minneapolis nightlife.

Industry changes and the Great Depression ended this boom. As mechanization displaced farmhands and railroad workers, forest depletion and chainsaws made many loggers “redundant.” Flour mills moved operations to Buffalo, New York, leaving hundreds of millers out of work.

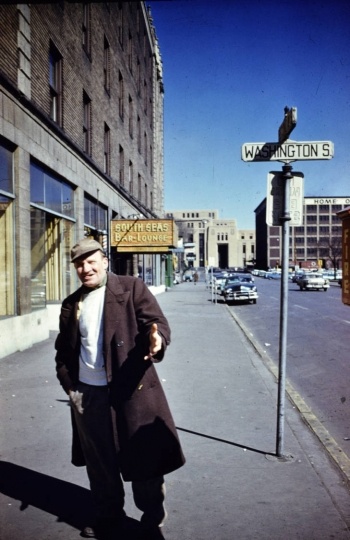

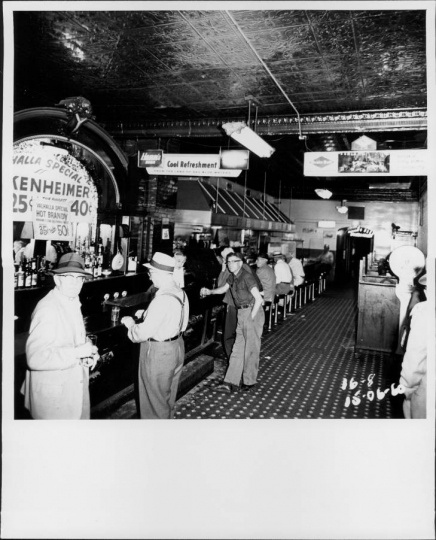

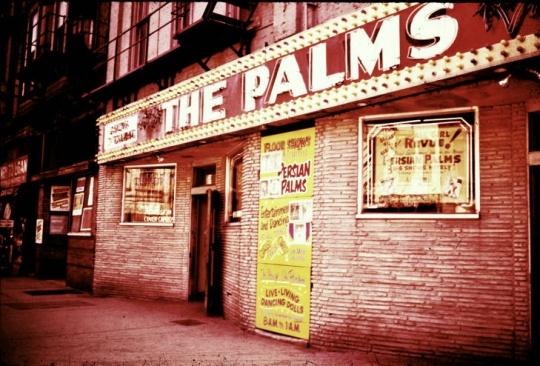

Faced with greater competition for work during the Depression, many of the same men who had built Minneapolis into a metropolis were now “marooned” on Skid Row. It became a de facto low-income retirement community for pensioners and the chronically unemployed. Better-off Minneapolitans still frequented Skid Row’s bars—the Persian Palms and Great Lakes Bar were especially popular—but warned their children that they would end up “on the skids” if they didn’t stay in school.

In the post-war era, Minneapolis planners and civic organizations grew concerned about declining population growth and property values as white residents and corporate offices moved in droves to the suburbs. Many blamed Skid Row for this shift; most of its residents were unemployed, unmarried, and on public benefits. They made up 44 percent of total arrests in Minneapolis, most for public drunkenness. Most buildings were not up to fire and sanitation code. Establishments like the Persian Palms, Dugout Bar, and Herb’s were refuges for the Twin Cities’ LGBTQ community. Many bars paid corrupt police and aldermen to ignore sex workers, sports betting, and regular closing times. Because of this relative openness to bribery, raids on gay bars were rare in the Gateway District, as in the rest of Minneapolis.

The Federal Highway Act of 1956 gave planners the excuse they had been looking for to deal with Skid Row while luring commuters back to Minneapolis with expressways and parking. The city council unanimously voted in favor of a federally funded plan to completely raze the area, and demolition began in 1958.

The brownstone Metropolitan Building (308 2nd Avenue South) was Minneapolis’s first skyscraper and is considered the greatest architectural loss of the more than 200 structures demolished. The most notable structures to come of the new development were the Northwest National Life and 100 Washington Square office buildings, both designed in the New Formalist style by Minoru Yamasaki. Nevertheless, the Gateway District was denigrated for years as a sea of parking lots and generic government buildings built without much concern for pedestrians.

Bibliography

Atkins, Annette. “At Home in the Heart of the City.” Minnesota History 58, nos. 5–6 (Spring/summer 2003): 286–304.

http://collections.mnhs.org/MNHistoryMagazine/articles/58/v58i05-06p286-304.pdf

“Gaming Case Suspect Held.” Minneapolis Morning Tribune, January 26, 1952.

Hart, Joseph. “Room at the Bottom.” City Pages, May 6, 1998.

https://web.archive.org/web/20100312080246/http://www.citypages.com/1998-05-06/news/room-at-the-bottom/8

Hart, Joseph, and Edwin C. Hirschoff. Down & Out: the Life and Death of Minneapolis’s Skid Row. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2002.

Hathaway, James T. The Liquor Patrol Limits of Minneapolis. 1985.

Murphy, Kevin. Queer Twin Cities. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010.

Nelson, Rick. “They Paved Paradise.” Minneapolis Star Tribune, December 10, 2011.

Shiffer, James Eli. The King of Skid Row: John Bacich and the Twilight Years of Old Minneapolis. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2016.

“Shown No Mercy: Police Arresting Every Drunken Man and Suspicious Person.” Minneapolis Tribune, October 18, 1897.

Wallace, Samuel E. Skid Row as a Way of Life. Totowa, NJ: Bedminster Press, 1965.

Related Resources

Primary

Liebling, Jerome, and Alan Trachtenberg. Jerome Liebling: The Minnesota Photographs. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1997.

Northern Lights and Insights #322

Minnesota Historical Society via Minnesota Reflections

Description: In this film footage, taken from a videocassette, Judith Martin, director of urban studies at the University of Minnesota and author of The Gateway, discusses the history, architecture and development of the Gateway District of Minneapolis on the television program Northern Lights and Insights, December 6, 1994.

https://reflections.mndigital.org/catalog/p16022coll38:57

“Down On Skid Row, a Tape’s Rolling! Special.” TPT Twin Cities PBS, 1998.

https://www.tpt.org/down-on-skid-row-a-tapes-rolling-special/

Secondary

Martin, Judith A., and Robert Silberman. The Gateway. [Minneapolis?]: R. Silberman and J. A. Martin, 1993.

Rosheim, David L. The Other Minneapolis, or The Rise and Fall of the Gateway, The Old Minneapolis Old Skid Row. Maquoketa, IA: Andromeda Press, 1978.

Related Images

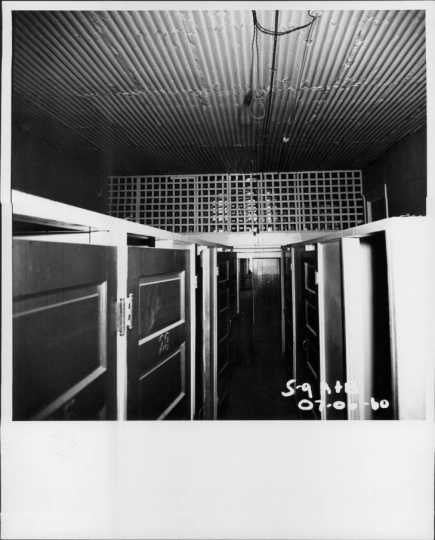

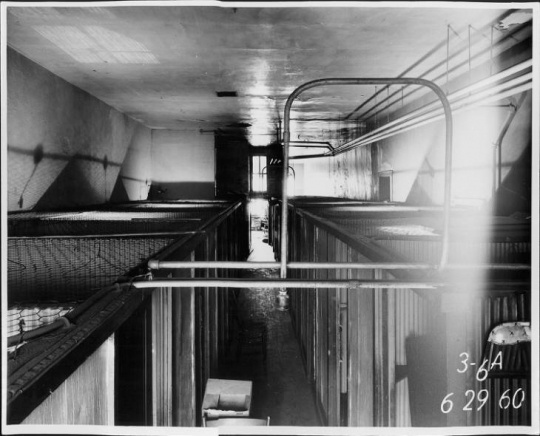

: “Cage Rooms” at the Standard Hotel (114 Hennepin Avenue South, Minneapolis), June 29, 1960. At the turn of the century, chicken-wire sub-ceilings were a common feature in cheaper boardinghouses in cities with a large temporary workforce. While Minneapolis banned the construction of new “cage hotels” in 1918, many lasted right up to the Gateway’s demolition. Some tenants who were evicted had been in their rooms since the 1920s.

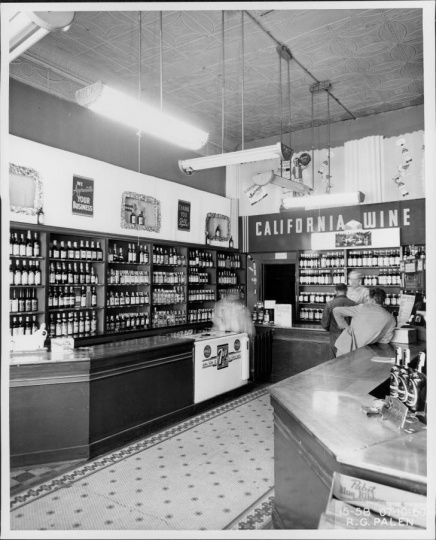

Interior of the California Wine Shop (29 Washington Avenue South, Minneapolis), July 10, 1960. In his documentary of life on Skid Row, the self-proclaimed “King of Skid Row,” John Bachich, recalled that bottles of wine could be bought “corked” or “uncorked” at California Wine Shop, near his own Sourdough Bar. While most of Skid Row’s residents did not have problems with alcohol, a minority were chronic alcoholics who served as frequent fodder for the Minneapolis Tribune’s investigative journalists.

Street view of Washington Avenue

Holding Location

More Information

Bridge Square, 1886

Holding Location

Laborers standing outside the Employment Bureau, 1908

Holding Location

More Information

Gateway Park, 1927

Holding Location

Putting up a Christmas Tree in Gateway Park, 1931.

Holding Location

Christmas Service at Gateway Gospel Mission, 1940.

Holding Location

Brody Loan Company storefront, 1950s

Holding Location

More Information

Unnamed man on the corner of Washington Avenue

All rights reserved

Holding Location

More Information

Bar scene at the Valhalla Café

All rights reserved

Holding Location

More Information

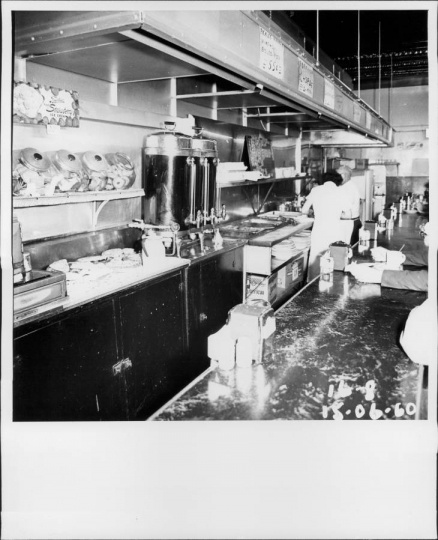

Diner side of Valhalla Café

All rights reserved

Holding Location

More Information

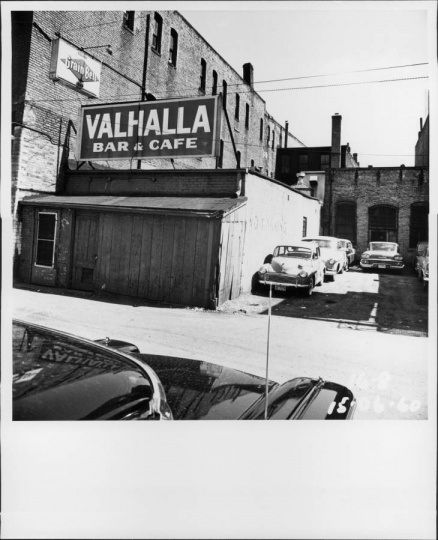

Cars in the parking lot of the Valhalla Café

All rights reserved

Holding Location

More Information

Pioneer Hotel Lobby

All rights reserved

Holding Location

More Information

Hallway of Pioneer Hotel

All rights reserved

Holding Location

More Information

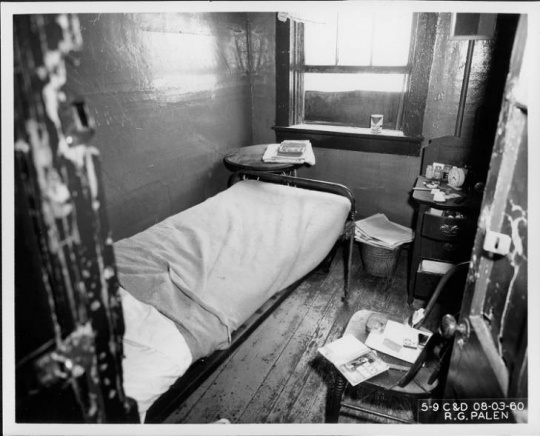

Lived-in room at the Pioneer Hotel

All rights reserved

Holding Location

More Information

Pioneer Hotel bathroom

All rights reserved

Holding Location

More Information

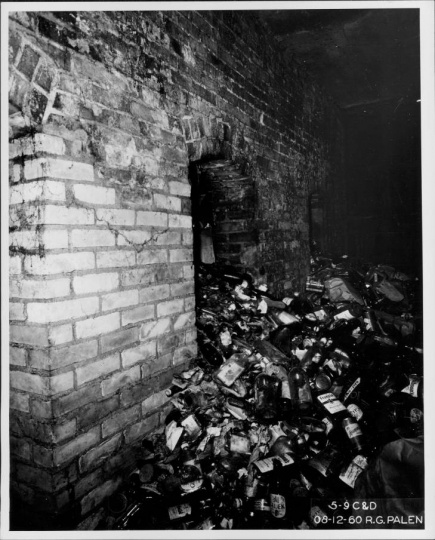

Bottle dump in the basement of the Pioneer Hotel

All rights reserved

Holding Location

More Information

“Cage Rooms” at the Standard Hotel

: “Cage Rooms” at the Standard Hotel (114 Hennepin Avenue South, Minneapolis), June 29, 1960. At the turn of the century, chicken-wire sub-ceilings were a common feature in cheaper boardinghouses in cities with a large temporary workforce. While Minneapolis banned the construction of new “cage hotels” in 1918, many lasted right up to the Gateway’s demolition. Some tenants who were evicted had been in their rooms since the 1920s.

Holding Location

More Information

California Wine Shop interior

Interior of the California Wine Shop (29 Washington Avenue South, Minneapolis), July 10, 1960. In his documentary of life on Skid Row, the self-proclaimed “King of Skid Row,” John Bachich, recalled that bottles of wine could be bought “corked” or “uncorked” at California Wine Shop, near his own Sourdough Bar. While most of Skid Row’s residents did not have problems with alcohol, a minority were chronic alcoholics who served as frequent fodder for the Minneapolis Tribune’s investigative journalists.

All rights reserved

Holding Location

More Information

Gutted interior of the Great Lakes Bar

All rights reserved

Holding Location

More Information

Interior of the Corner Grocery

Interior of the Corner Grocery (129 Nicollet Avenue, Minneapolis), August 3, 1860.

Holding location: Hennepin County Library

All rights reserved

Holding Location

More Information

Interior of the Stockholm Bar

All rights reserved

Holding Location

More Information

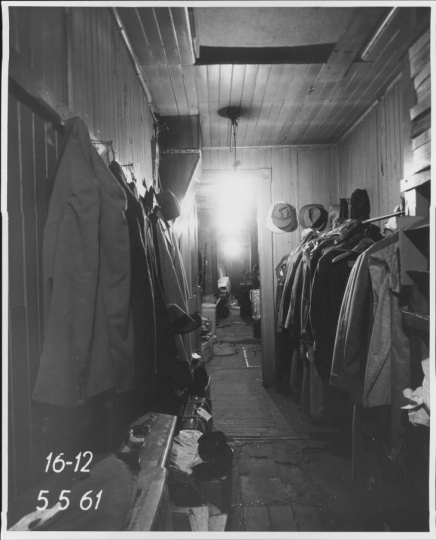

Coatroom at the Beaufort Hotel

All rights reserved

Holding Location

More Information

Persian Palms Nightclub

All rights reserved

Holding Location

More Information

Related Articles

Turning Point

The Minneapolis City Council passes an ordinance in 1884 to limit saloon licenses on the “West Bank” to areas roughly equivalent to the Gateway District and Cedar-Riverside neighborhood, ironically hastening the old downtown’s transition from a mixed-income immigrant family neighborhood into a concentrated hub of flophouses and saloons.

Chronology

1884

1897

1902

1910

1917

1918

1930s

1955

Late 1950s

1965

1960s

2018

Bibliography

Atkins, Annette. “At Home in the Heart of the City.” Minnesota History 58, nos. 5–6 (Spring/summer 2003): 286–304.

http://collections.mnhs.org/MNHistoryMagazine/articles/58/v58i05-06p286-304.pdf

“Gaming Case Suspect Held.” Minneapolis Morning Tribune, January 26, 1952.

Hart, Joseph. “Room at the Bottom.” City Pages, May 6, 1998.

https://web.archive.org/web/20100312080246/http://www.citypages.com/1998-05-06/news/room-at-the-bottom/8

Hart, Joseph, and Edwin C. Hirschoff. Down & Out: the Life and Death of Minneapolis’s Skid Row. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2002.

Hathaway, James T. The Liquor Patrol Limits of Minneapolis. 1985.

Murphy, Kevin. Queer Twin Cities. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010.

Nelson, Rick. “They Paved Paradise.” Minneapolis Star Tribune, December 10, 2011.

Shiffer, James Eli. The King of Skid Row: John Bacich and the Twilight Years of Old Minneapolis. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2016.

“Shown No Mercy: Police Arresting Every Drunken Man and Suspicious Person.” Minneapolis Tribune, October 18, 1897.

Wallace, Samuel E. Skid Row as a Way of Life. Totowa, NJ: Bedminster Press, 1965.

Related Resources

Primary

Liebling, Jerome, and Alan Trachtenberg. Jerome Liebling: The Minnesota Photographs. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1997.

Northern Lights and Insights #322

Minnesota Historical Society via Minnesota Reflections

Description: In this film footage, taken from a videocassette, Judith Martin, director of urban studies at the University of Minnesota and author of The Gateway, discusses the history, architecture and development of the Gateway District of Minneapolis on the television program Northern Lights and Insights, December 6, 1994.

https://reflections.mndigital.org/catalog/p16022coll38:57

“Down On Skid Row, a Tape’s Rolling! Special.” TPT Twin Cities PBS, 1998.

https://www.tpt.org/down-on-skid-row-a-tapes-rolling-special/

Secondary

Martin, Judith A., and Robert Silberman. The Gateway. [Minneapolis?]: R. Silberman and J. A. Martin, 1993.

Rosheim, David L. The Other Minneapolis, or The Rise and Fall of the Gateway, The Old Minneapolis Old Skid Row. Maquoketa, IA: Andromeda Press, 1978.