Topics

Category

Era

St. Mary’s Orthodox Cathedral, Minneapolis

St. Mary’s Orthodox Cathedral, completed in 1906, was the home church of Rusyn immigrants to Minneapolis in the late nineteenth century. As these immigrants continued to arrive from the Austro-Hungarian Empire in the 1900s, St. Mary’s became the Mother Church of Eastern Orthodoxy in the Twin Cities region.

In 1877 Northeast Minneapolis began to attract immigrants from a small Central European ethnic group. A Slavic people, they were called, variously, Rusyns, Ruthenians, Carpatho-Rusyns, and Carpatho-Ruthenians, since many lived in the region below the Carpathian Mountains (now eastern Slovakia). In the late nineteenth century they were subjects of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

For hundreds of years Rusyns had belonged to the Eastern Rite Catholic tradition, a subset of the larger Roman Catholic world. Their roots, however, were in the Byzantine and Russian Orthodox Church. In Minneapolis, although they were encouraged to assimilate with Latin Rite Roman Catholics, Rusyns created a community that reflected their own unique religious and cultural history. Visiting Eastern Rite clergy from the eastern United States helped advance this dream. By 1887, their numbers had grown, and a group was organized to form and build a church.

St Mary’s Greek Catholic Church, a small wood-frame building, opened in 1888 at the corner of 5th Street NE and 17th Avenue NE in Minneapolis. The following year, in response to the petition of parishioners, the Eastern Rite Catholic Bishop of Presov in eastern Slovakia sent a learned, widowed priest named Alexis Toth to be their pastor. His first service was held on Thanksgiving Day. A few weeks later, on December 19, Toth went to St Paul to present his credentials to John Ireland, the local Roman Catholic archbishop.

The meeting did not go well. Upon learning that Toth had been married, as Eastern Rite clergy most often are, Ireland rejected his credentials and refused to allow him to serve as a priest. Ireland forbade use of the Eastern Rite liturgy and directed the Rusyn immigrants to worship at the local Polish parish of the Latin Church.

This they did not do. Toth continued to serve as a priest, and he soon made contact with the Higher Church Administration of the Russian Orthodox Church in North America. Two trips to the Orthodox cathedral in San Francisco led to the informal (1891) and then the formal (1892) reception of Fr. Alexis and the parish community into the Orthodox Church as part of the Russian Orthodox Diocese of the Aleutians and North America. This reception was an important positive moment in the life of the community in Minneapolis, and in the return of Eastern Rite Catholics to Orthodoxy throughout the United States and in Eastern Europe.

When the congregation’s first dedicated building burned down in 1904, the congregation took action. With the assistance of the Russian Holy Synod, it hired Minneapolis architect Victor Cordella to adapt and build a “stone” (that is, brick) replacement modeled on the old cathedral of the Elevation of the Holy Cross in Omsk, Siberia. Alterations to the blueprint were made in light of the size of the lot, which was too narrow. Among these were the addition of stained glass windows—an innovation in Orthodox church architecture—as an integral part of the articulation of sacred space.

When the cathedral opened in 1906, its congregation had nearly nine hundred members. Still, the building’s $40,000 cost drained the church’s resources. Despite an annual subsidy of $1100 from the Russian government and a $1029 gift from Tsar Nicholas II, the cathedral opened without furnishings, decoration, or central heating. Those arrived as money permitted; pews were installed in 1934.

Despite an annual subsidy from the Holy Synod and personal financial support and gifts from the Imperial family, the parish struggled. Yet it endured. The decorations added over the years include a white icon screen at the front of the sanctuary, a large chandelier, a painted dome, and stained glass. There are also icon-style paintings—some life size—of Jesus, Mary, and Orthodox saints. Renovations in 1982 and in the years following 2005 both maintained and expanded traditional iconographic programs in the church.

Bibliography

Dyrud, Keith P. “East Slavs: Rusins, Ukrainians, Russians, and Belorussians.” In They Chose Minnesota: A Survey of the State’s Ethnic Groups, edited by June Drenning Holmquist, 405–422. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society 1981.

Lathrop, Alan K. Churches of Minnesota: An Illustrated Guide. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 2003.

St. Mary’s Orthodox Cathedral. St. Mary’s Orthodox Cathedral 100th Anniversary, 1887–1987. Minneapolis: The Cathedral, 1987.

Related Resources

Secondary

The Price of Freedom: The Story of 14 Members of St. Mary’s Russian Orthodox Cathedral. Minneapolis: N.p., [2001?].

Related Images

St. Mary’s Orthodox Cathedral

All rights reserved

Holding Location

The original St. Mary’s Orthodox Cathedral building

Public domain

Holding Location

More Information

St. Mary’s Orthodox Cathedral in Minneapolis

Public domain

Holding Location

More Information

St. Mary’s Orthodox Cathedral sanctuary

Public domain

Holding Location

More Information

St. Mary’s Orthodox Cathedral sanctuary with an icon screen and banners

Public domain

Holding Location

More Information

Interior of the sanctuary in St. Mary’s Orthodox Cathedral

Public domain

Holding Location

More Information

Procession at St. Mary’s Orthodox Cathedral

Public domain

Holding Location

More Information

St. Nicholas Cathedral, Omsk

Holding Location

More Information

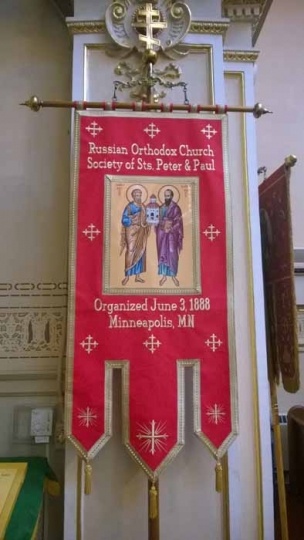

Banner inside St. Mary’s Orthodox Cathedral, Minneapolis

All rights reserved

Holding Location

Banner inside St. Mary’s Orthodox Cathedral

All rights reserved

Holding Location

Dome and chandelier

All rights reserved

Holding Location

Exterior of St. Mary’s Orthodox Cathedral

All rights reserved

Holding Location

Icon inside St. Mary’s Orthodox Cathedral, Minneapolis

All rights reserved

Holding Location

Sanctuary of St. Mary’s Orthodox Cathedral

All rights reserved

Holding Location

Stained glass window inside St. Mary’s Orthodox Cathedral, Minneapolis

All rights reserved

Holding Location

Sanctuary of St. Mary's Cathedral after renovation

All rights reserved

Holding Location

Side wall of St. Mary's Orthodox Cathedral sanctuary

All rights reserved

Holding Location

A side wall of St. Mary's Orthodox Cathedral sanctuary

All rights reserved

Holding Location

Related Articles

Turning Point

On January 24, 1904, the original St. Mary’s Church is destroyed by fire. Construction on a new church begins the next year.

Chronology

1877

1887

1889

1889

1891

1892

1892

1904

1905

1906

1934

1967

1982

2006

Bibliography

Dyrud, Keith P. “East Slavs: Rusins, Ukrainians, Russians, and Belorussians.” In They Chose Minnesota: A Survey of the State’s Ethnic Groups, edited by June Drenning Holmquist, 405–422. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society 1981.

Lathrop, Alan K. Churches of Minnesota: An Illustrated Guide. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 2003.

St. Mary’s Orthodox Cathedral. St. Mary’s Orthodox Cathedral 100th Anniversary, 1887–1987. Minneapolis: The Cathedral, 1987.

Related Resources

Secondary

The Price of Freedom: The Story of 14 Members of St. Mary’s Russian Orthodox Cathedral. Minneapolis: N.p., [2001?].