Topics

Category

Era

Glensheen Historic Estate

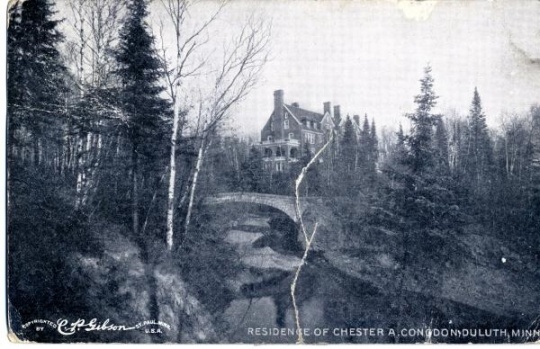

Glensheen, a mansion and grounds completed in 1908 on the shores of Lake Superior in Duluth, was built by Chester and Clara Congdon. It is famous for its beauty inside and out, and as the site of one of Minnesota’s most notorious murders.

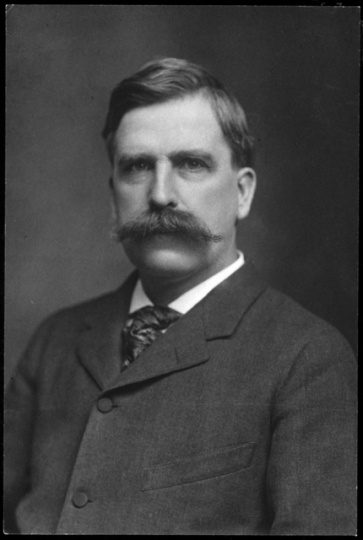

Chester Congdon and Clara Bannister, children of Methodist ministers, met at Syracuse University in New York in 1871. They married and moved to St. Paul ten years later. After a slow start, Chester prospered in the law and took to real estate speculation, mostly in the Pacific Northwest. Overall, he lost money on his investments.

The family moved to Duluth in 1892 when Chester saw opportunity in the booming city and the newly industrializing Mesabi Iron Range. As a lawyer for the Oliver Iron Mining Company, he grappled with Andrew Carnegie and J. D. Rockefeller—a competition that drew national attention to Minnesota—and made millions of dollars. In 1901, he formed the Chemung Iron Company and made millions more.

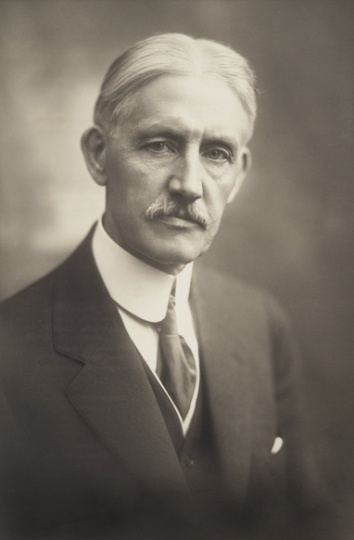

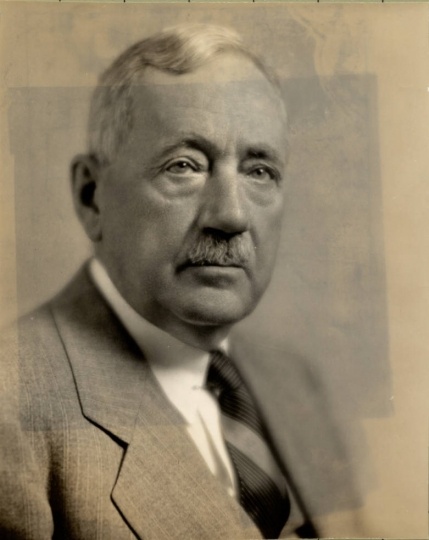

In 1903, the Congdons chose land three miles from downtown Duluth, facing Lake Superior, for a new residence. To design the house and grounds they selected Clarence H. Johnston (1859–1936), Charles Wellford Leavitt (1871–1928), and William A. French (1863–1942.)

Johnston, designer of many Summit Avenue mansions, produced a thirty-nine-room giant in the Jacobean Revival style that mimicked English country houses from four centuries earlier. The outside appearance is elegant: an asymmetrical mass of brick, with granite trim and prominent gables. Johnston and the Congdons paid close attention to infrastructure; the estate had its own reservoir, a coal delivery system, and central humidification.

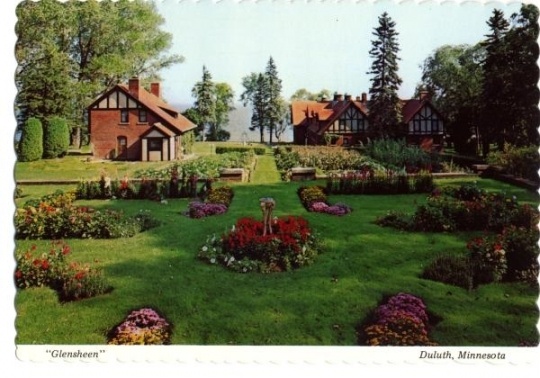

Leavitt, from New York City, designed the grounds. He included formal gardens, lakeside terraces, a bowling green, walking paths and footbridges, more than thirty species of trees, and thousands of shrubs.

The name “Glensheen” reflects the site. Glen, a Scots word for a narrow valley, refers to the ravines of Tischer Creek and Bent Brook, which frame the estate; “sheen” either comes from Sheen, the Congdons’ ancestral village in England, or from the reflection of light off the lake.

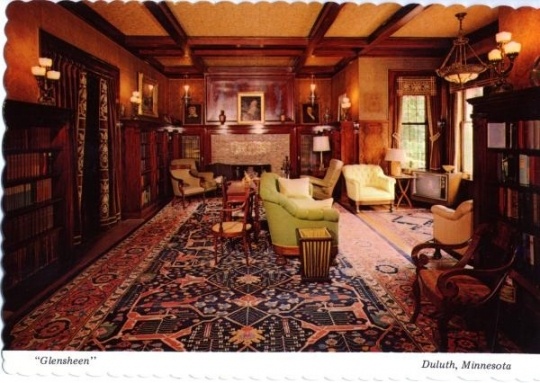

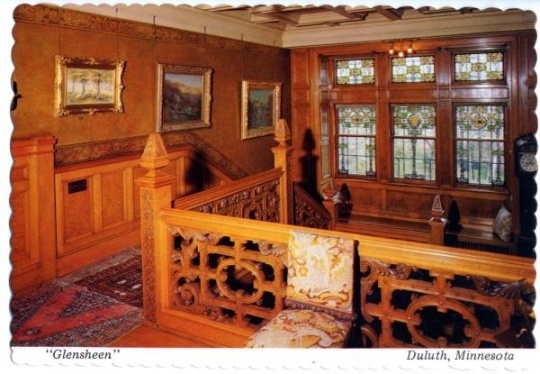

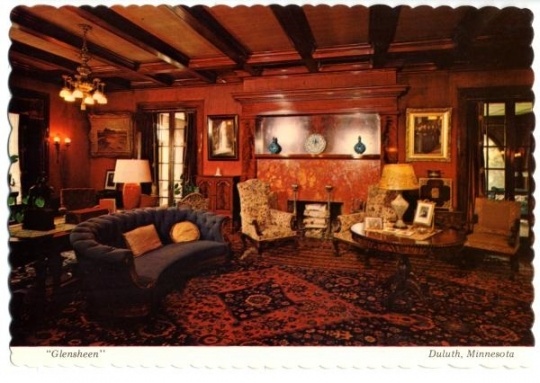

Glensheen’s design star is French, a St. Paul interior decorator and designer. With the Congdons, he chose fine materials: silver for light fixtures, gold leaf for ceilings, oak and walnut woodwork, and Algerian marble. He used both art nouveau and Arts and Crafts styles, which were lighter and more elegant than the busy interiors of late-nineteenth-century mansions.

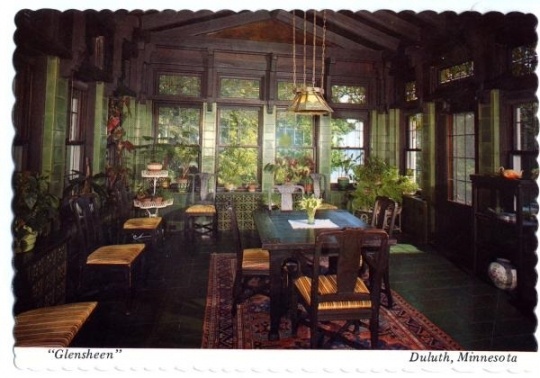

The interior features hand-carved railings and art-glass windows. The dining room and library overlook the terrace and garden below and Lake Superior beyond. The breakfast room, designed by John Bradstreet of Minneapolis, is considered a highlight for its green tiled walls and floors, as well as for its lake views.

Despite Glensheen’s luxury and size, architectural historian Larry Millett finds it “warm and livable,” with “a surprising sense of intimacy.” Because the house remained in the Congdon family until 1978, little has changed over time. Millett calls it the most intact house of its kind in Minnesota.

Chester Congdon died in 1916, without completing his vision for a highway linking Duluth to Canada; it opened in 1923 as North Shore Scenic Drive. Clara lived in Glensheen until her death in 1950. Their daughter Elisabeth, the last of their seven children to die, lived there for the rest of her life. She never married but adopted two daughters, Marjorie and Jennifer, in 1932.

On the night of June 26, 1977, Elisabeth Congdon and her nurse, Velma Pietila, were murdered by an intruder. Suspicion fell on Marjorie and her husband, Roger Caldwell. Marjorie had lived a troubled life and, before the murder, demanded money from Elisabeth. Caldwell was convicted of the murder in 1978; Marjorie was acquitted in 1979.

The Minnesota Supreme Court reversed Caldwell’s conviction in 1983. In return for a sentence of time served, Caldwell admitted to the murders but refused to implicate his then ex-wife, Marjorie. He took his own life in 1988. Though Marjorie inherited part of the Congdon fortune, her life remained troubled. Her third husband died a suspicious death, and she served time in an Arizona prison for arson.

Prior to the murder in 1969, the Congdon family willed Glensheen to the University of Minnesota–Duluth. It opened as a museum in 1979 and has become one of Minnesota’s top historic tourist attractions.

Bibliography

Berini, Nancy. “Glensheen in a New Light.” Lake Superior Port Cities 4, no. 1 (1982): 29–44.

Dierckins, Tony. “Building the Fortune That Built Glensheen: Chester Congdon and America’s Robber Barons.” Zenith City, May 1, 2015.

Hartman, Dan. “A Legacy Forgotten: Chester Congdon and the North Shore Drive.” The Glensheen Collection.

https://medium.com/the-glensheen-collection/north-shore-drive-and-chester-a-romance-forgotten-8af7c81b131b

Hoover, Roy O. A Lake Superior Lawyer: A Biography of Chester Adgate Congdon. Duluth: Superior Partners, 1997.

Kimball, Joe. Secrets of the Congdon Mansion. Minneapolis: Jackay Publishing, 1991.

Larson, Paul Clifford. Minnesota Architect: The Life and Work of Clarence H. Johnston. Afton, MN: Afton Historical Society Press, 1996.

Millett, Larry. Minnesota’s Own: Preserving Our Grand Homes. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2014.

Tenuta, James A. “Glensheen Opens Its Doors to the Past.” Lake Superior Port Cities 1, no. 3 (1979): 6–13.

Related Resources

Primary

A/.H332g

Guilford G. Hartley and family scrapbooks, 1882–1960

Manuscript Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

Description: Materials for 1904–1922 cover Hartley’s association with Chester A. Congdon in mining ventures on the Mesabi Iron Range.

U6192

Congdon family papers, 1843–1983

Archives and Special Collections, University of Minnesota, Duluth

Description: Photographs, correspondence, diaries, publications, ephemera, and business, financial, and political records related to the family of Chester A. Congdon, 1853–1916.

https://archives.lib.umn.edu/repositories/22/resources/9334

Secondary

Millett, Larry. Once There Were Castles: Lost Mansions and Estates of the Twin Cities. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2001.

Sandeen, Ernest R. St. Paul’s Historic Summit Avenue. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2004.

Web

Glensheen. About.

http://glensheen.org/about

Glensheen Collection blog.

https://medium.com/the-glensheen-collection

"Glensheen, the Historic Congdon Estate." University of Minnesota, Duluth.

http://hdl.handle.net/11299/183666

"Historic Glensheen Estate and the Congdon Family." Kathryn A. Martin Library, University of Minnesota, Duluth.

https://libguides.d.umn.edu/glensheen

Related Images

Glensheen Mansion

Glensheen historic estate, August 5, 2006. Photo by Wikimedia Commons user Derek Heidelberg.

Public domain

Postcard of Glensheen from the lake

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

Chester A. Congdon

Public domain

Holding Location

More Information

Clara Bannister Congdon

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

Clarence Johnston

Public domain

Holding Location

More Information

William A. French

Holding Location

Articles

Glensheen from the air

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

Glensheen from terrace garden

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

Glensheen gardens and outbuildings

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

Glensheen library

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

Glensheen staircase

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

Glensheen living room

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

Glensheen breakfast room

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

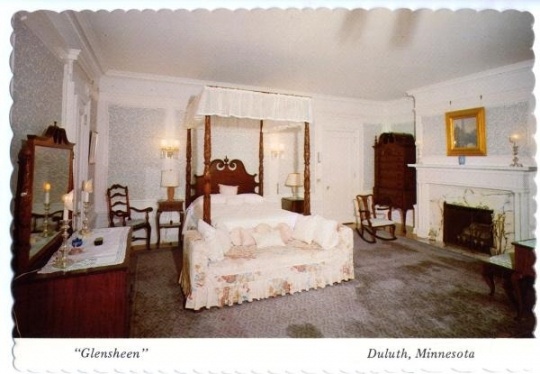

Glensheen bedroom

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

Glensheen, Duluth

Articles

More Information

Related Articles

Turning Point

In 1903, Clara and Chester Congdon decide to build a new house overlooking Lake Superior in Duluth.

Chronology

1871

1879

1881

1892

1894

1903

1908

1908

1916

1932

1950

1977

1978

1979

1983

2015

Bibliography

Berini, Nancy. “Glensheen in a New Light.” Lake Superior Port Cities 4, no. 1 (1982): 29–44.

Dierckins, Tony. “Building the Fortune That Built Glensheen: Chester Congdon and America’s Robber Barons.” Zenith City, May 1, 2015.

Hartman, Dan. “A Legacy Forgotten: Chester Congdon and the North Shore Drive.” The Glensheen Collection.

https://medium.com/the-glensheen-collection/north-shore-drive-and-chester-a-romance-forgotten-8af7c81b131b

Hoover, Roy O. A Lake Superior Lawyer: A Biography of Chester Adgate Congdon. Duluth: Superior Partners, 1997.

Kimball, Joe. Secrets of the Congdon Mansion. Minneapolis: Jackay Publishing, 1991.

Larson, Paul Clifford. Minnesota Architect: The Life and Work of Clarence H. Johnston. Afton, MN: Afton Historical Society Press, 1996.

Millett, Larry. Minnesota’s Own: Preserving Our Grand Homes. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2014.

Tenuta, James A. “Glensheen Opens Its Doors to the Past.” Lake Superior Port Cities 1, no. 3 (1979): 6–13.

Related Resources

Primary

A/.H332g

Guilford G. Hartley and family scrapbooks, 1882–1960

Manuscript Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

Description: Materials for 1904–1922 cover Hartley’s association with Chester A. Congdon in mining ventures on the Mesabi Iron Range.

U6192

Congdon family papers, 1843–1983

Archives and Special Collections, University of Minnesota, Duluth

Description: Photographs, correspondence, diaries, publications, ephemera, and business, financial, and political records related to the family of Chester A. Congdon, 1853–1916.

https://archives.lib.umn.edu/repositories/22/resources/9334

Secondary

Millett, Larry. Once There Were Castles: Lost Mansions and Estates of the Twin Cities. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2001.

Sandeen, Ernest R. St. Paul’s Historic Summit Avenue. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2004.

Web

Glensheen. About.

http://glensheen.org/about

Glensheen Collection blog.

https://medium.com/the-glensheen-collection

"Glensheen, the Historic Congdon Estate." University of Minnesota, Duluth.

http://hdl.handle.net/11299/183666

"Historic Glensheen Estate and the Congdon Family." Kathryn A. Martin Library, University of Minnesota, Duluth.

https://libguides.d.umn.edu/glensheen