Topics

Category

Era

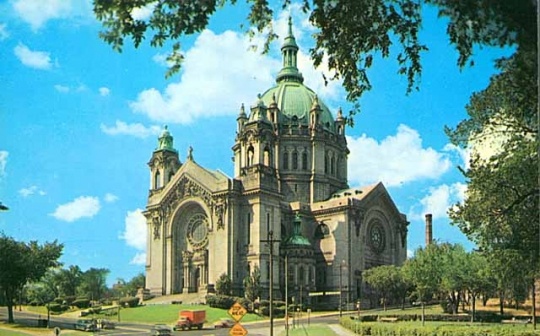

Cathedral of St. Paul

There have been four Roman Catholic cathedrals in St. Paul. The first three were built between 1841 and 1858. The fourth, and the most architecturally distinctive, opened in 1915. Since then, no building in the Twin Cities has approached it in ambition or magnificence.

The massive granite cathedral at the foot of Summit and Selby Avenues is the fourth in the history of the archdiocese of St. Paul and Minneapolis. The first was Father Lucien Galtier’s log-cabin Chapel of St. Paul, elevated to the status of cathedral with the 1851 arrival of Bishop Joseph Cretin. A three-floor brick building succeeded it later in 1851; a bigger one in stone followed in 1856. Both stood in downtown St. Paul.

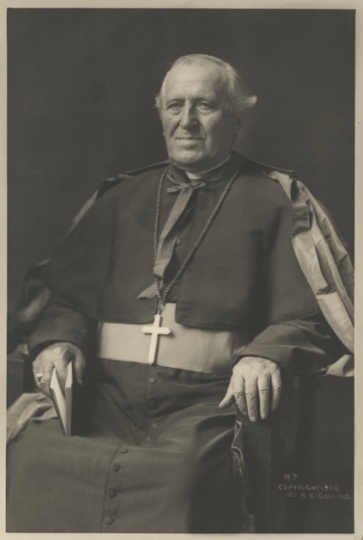

Between 1850 and 1900 St. Paul grew from a village to a city of over 160,000. Many of the new citizens were Roman Catholics, mostly of German and Irish origin. In 1904 Archbishop John Ireland (1838–1918), a potato-famine Irish immigrant and a protégé of Joseph Cretin’s, decided to build yet another cathedral.

Ireland hired French architect Emmanuel Masqueray (1861–1917). Together they conceived a building with a grandeur rivaled only by Cass Gilbert’s state capitol, completed in 1905.

The commanding site they chose sits on the edge of a bluff then called St. Anthony Hill. In a biblical context, it can be seen as permitting the House of God to look down, literally and symbolically, on moneychangers (as represented by downtown St. Paul) and Caesar (as represented by the state capitol).

Construction began in 1906. The building opened, undecorated inside, in 1915. Masqueray died in 1917, Ireland a year later. The Boston firm of Maginnis and Walsh was hired in 1923 to complete the interior, a project that went on until 1940.

The exterior is Rockville (Minnesota) granite topped by a copper dome 306 feet from the ground at its apex. Above the main, east-facing entry, a relief sculpture of Christ sending his apostles out to preach to the world reaches to the peak. It is flanked by statues of St. Peter and St. Paul designed by Leon Hermant of Chicago and carved by John Garratti of St. Paul. Its overall appearance is severe; the granite is gray, the dome’s copper oxidized to a cocoa brown.

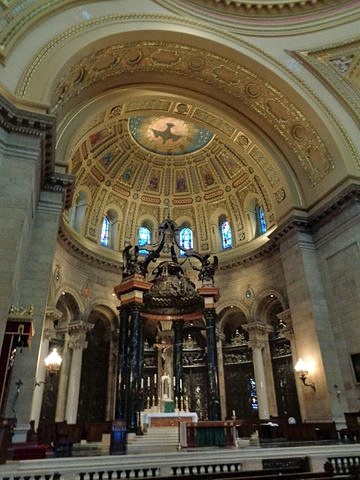

The interior, by contrast, abounds in color—marble, metalwork, stained glass, and painting. There are at least twenty-five varieties of marble on display from nine countries. Their colors range from radiant red (Rojo Alicante from Spain in the Sacred Heart Chapel) to deep green (Tinos from Greece in the vestibules) to a black flecked with gold (Portora from Italy in the baldachin columns.)

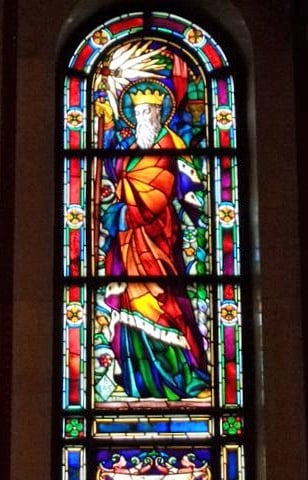

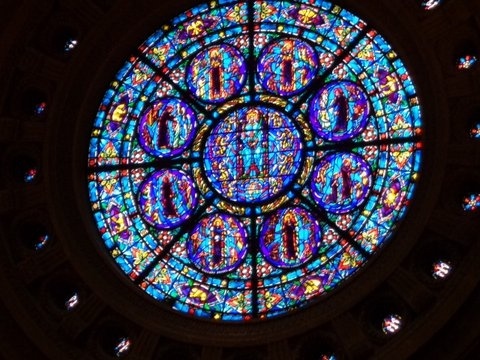

The bronze screen behind the altar is worked in figures and patterns. All of the eleven chapels feature stained glass windows. Three enormous rose windows brighten the sanctuary; one of them portrays North American martyrs and North Woods wildlife. The rose windows are by Charles Connick, the grilles by Albert Atkins, and the altar and baldachin (altar cover) by Whitney Warren.

An unusual feature of the cathedral is the Shrine of Nations: six chapels arrayed in a semicircle behind the altar, installed 1926–1928. These commemorate ethnic groups that contributed labor and money to the Cathedral project: Irish, French Canadian, Italian, German, and Slavic. A sixth, of St. Therese, represents other ethnic groups in general. Each contains a central statue of a patron saint, two flanking stained glass windows, and, in the floor, a circular slab of marble from the country.

There are two large frescos by Mark Balma. One shows Bishop Cretin arriving by canoe in 1851, with the Chapel of St. Paul in the background. The other portrays Archbishop Ireland about to enter the cathedral for its first mass in spring of 1915.

At each of the four corners of the main seating area stands a bigger-than-life statue of one of the four evangelists. The interior space is vast beneath the high dome. The main dome and the high ceiling over the altar are both highly decorated, adding to the variety of color and setting off the soft glow of the Mankato travertine walls and columns.

A major renovation took place between 2001 and 2003. Workers repaired the exterior and completely re-sheathed the copper dome.

Bibliography

Cain, Sr. Joan, and Paul Nelson. Rocky Roots, Geology and Stone Construction in Downtown St. Paul. St. Paul: Ramsey County Historical Society, 2004.

Durkin, Sister Mary Cabrini, ed. Cathedral of St. Paul, Living Mission of the Church. Strasbourg, France: Editions du Signe, 1998.

Hansen, Eric C. Cathedral of Saint Paul, an Architectural Biography. St. Paul: Cathedral of St. Paul, 1990.

Millet, Larry. AIA Guide to the Twin Cities: the Essential Source on the Architecture of Minneapolis and St. Paul. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 2007.

Related Resources

Primary

I.199

Cathedral of St. Paul [graphic], c.1950–1957

Audiovisual Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/sv000092.xml

Description: The collection contains thirty-one black-and-white photographs of the Cathedral of St. Paul.

M454

John Ireland papers, 1825–1948 (bulk 1854–1918)

Manuscript Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/m0454.pdf

Description: Includes records relating to the building of multiple St. Paul cathedrals.

Secondary

Boyle, Dia. Stone and Glass: The Meaning of the Cathedral of St. Paul. St. Paul: Cathedral of St. Paul, 2008.

Lathrop, Alan K. “A French Architect in Minnesota: Emmanuel L. Masqueray, 1861–1917.” Minnesota History 47, no. 2 (Summer 1980): 42–56.

http://collections.mnhs.org/MNHistoryMagazine/articles/47/v47i02p042-056.pdf

Saint Paul Cathedral, National Register of Historic Places Nomination File, State Historic Preservation Office, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

http://www.mnhs.org/preserve/nrhp/NRDetails.cfm-NPSNum=74001039.html

http://www.mnhs.org/preserve/nrhp/nomination/74001039.pdf

Web

Archdiocese of St. Paul and Minneapolis. Our History.

http://www.archspm.org/about-us/history/

Cathedral of St. Paul. History.

http://www.cathedralsaintpaul.org/history

Related Images

St. Paul Cathedral

Chapel of St. Paul

Public domain

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

Norman Kittson mansion

Public domain

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

John Ireland, St. Paul

Public domain

Holding Location

More Information

Emmanuel Masqueray

Public domain

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

Third Cathedral of St. Paul

Public domain

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

Fourth Cathedral of St. Paul

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

St. Peter chapel

All rights reserved

Holding Location

Articles

Tinos marble

All rights reserved

Holding Location

Articles

Saint Wenceslaus window

All rights reserved

Holding Location

Articles

Main seating area

All rights reserved

Holding Location

Articles

Statue of St. Paul

All rights reserved

Holding Location

Articles

Altar and baldachin

All rights reserved

Holding Location

Articles

Altar ceiling

All rights reserved

Holding Location

Articles

Grille detail

All rights reserved

Holding Location

Articles

Saints Cyril and Methodius, Shrine of Nations

All rights reserved

Holding Location

Articles

Statue of St. Luke

All rights reserved

Holding Location

Articles

North rose window

All rights reserved

Holding Location

Articles

Dome ceiling

All rights reserved

Holding Location

Articles

Cross station

All rights reserved

Holding Location

Articles

Related Articles

Turning Point

Observing the overflow crowds at the third cathedral (at Sixth and St. Peter Streets, and then fifty-one years old) in 1904, Archbishop John Ireland decides that a new cathedral must be built.

Chronology

1841

July 2, 1851

Late Fall, 1851

1856

March 31, 1904

April 9, 1904

March 1905

July 5, 1906

November 1906

1907

1914

1915

1917

1918

1940

2003

Bibliography

Cain, Sr. Joan, and Paul Nelson. Rocky Roots, Geology and Stone Construction in Downtown St. Paul. St. Paul: Ramsey County Historical Society, 2004.

Durkin, Sister Mary Cabrini, ed. Cathedral of St. Paul, Living Mission of the Church. Strasbourg, France: Editions du Signe, 1998.

Hansen, Eric C. Cathedral of Saint Paul, an Architectural Biography. St. Paul: Cathedral of St. Paul, 1990.

Millet, Larry. AIA Guide to the Twin Cities: the Essential Source on the Architecture of Minneapolis and St. Paul. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 2007.

Related Resources

Primary

I.199

Cathedral of St. Paul [graphic], c.1950–1957

Audiovisual Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/sv000092.xml

Description: The collection contains thirty-one black-and-white photographs of the Cathedral of St. Paul.

M454

John Ireland papers, 1825–1948 (bulk 1854–1918)

Manuscript Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/m0454.pdf

Description: Includes records relating to the building of multiple St. Paul cathedrals.

Secondary

Boyle, Dia. Stone and Glass: The Meaning of the Cathedral of St. Paul. St. Paul: Cathedral of St. Paul, 2008.

Lathrop, Alan K. “A French Architect in Minnesota: Emmanuel L. Masqueray, 1861–1917.” Minnesota History 47, no. 2 (Summer 1980): 42–56.

http://collections.mnhs.org/MNHistoryMagazine/articles/47/v47i02p042-056.pdf

Saint Paul Cathedral, National Register of Historic Places Nomination File, State Historic Preservation Office, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

http://www.mnhs.org/preserve/nrhp/NRDetails.cfm-NPSNum=74001039.html

http://www.mnhs.org/preserve/nrhp/nomination/74001039.pdf

Web

Archdiocese of St. Paul and Minneapolis. Our History.

http://www.archspm.org/about-us/history/

Cathedral of St. Paul. History.

http://www.cathedralsaintpaul.org/history