Topics

Category

Era

Frontenac State Park

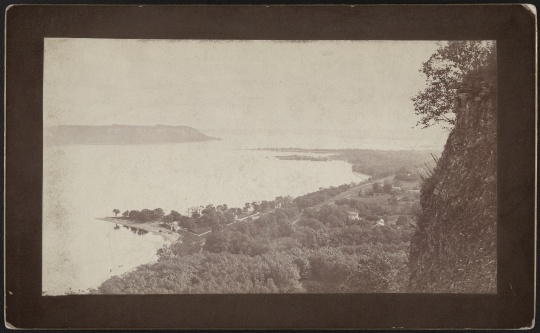

Frontenac State Park stretches over 2,600 acres along the widening of the Mississippi River known as Lake Pepin. The park is located in Goodhue County on the Mississippi Flyway, one of four major migratory bird routes in North America. With more than 260 bird species recorded within its boundaries, the park is a prime destination for Minnesota birders.

The rock-faced cliffs and upland prairie of Frontenac State Park began to form 500 million years ago, when the land was covered by a shallow sea. Over time, sediment filtered out of the seawater, hardening into limestone, dolostone, and erosive sandstone. Following the last Ice Age 10,000 years ago, the meltwaters of Glacial River Warren shaped the steep valley, floodplain, and mud flats that now define the Lake Pepin shore. Current-day reminders of the glacial era include the remains of a nineteenth-century limestone quarry and the naturally carved rock called Iŋyaŋ Tiyopa (stone door), sacred to Dakota and Meskwaki people.

From the earliest days of human contact, Lake Pepin’s southwestern shore served as a gathering place. Archaeological evidence indicates that builders of a burial-mound network, the Havana Hopewell people, met there from about 400 BCE to 500 CE, trading food and tools while sharing customs and practices. Beginning around 1600 CE, ancestors of Dakota people made the area part of their annual cycle of hunting, fishing, harvesting wild rice, and tapping maple syrup.

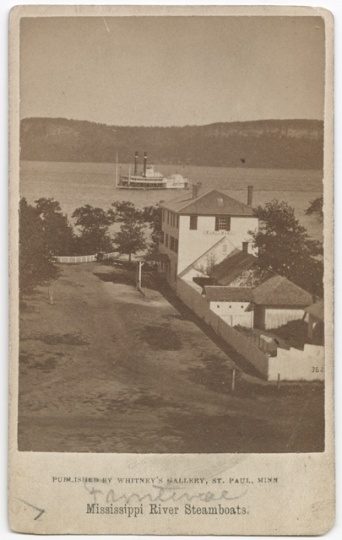

French expeditions traveled from Canada to Lake Pepin in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, seeking trade with the Dakota and searching for a route to the Pacific Ocean. When steamboats proved the Upper Mississippi was navigable, tourism began, with voyages between St. Louis and St. Paul.

In 1853, shopkeeper Evert Westervelt and Cincinnati lawyer Israel Garrard platted a 320-acre town called Westervelt, designating thirty-five acres for village parks. Over the next few years Garrard bought out Westervelt’s shares, expanded the town, quadrupled the parks, and (in 1859) changed the town’s name to Frontenac. Garrard continued developing his lakeside resort while buying a corridor of land lining twelve miles along the lakeshore. In the 1860s, paddleboats tied up at the Frontenac landing, delivering passengers who stayed a night, a week, or a month at the posh, three-story Lake Side Hotel that earned Frontenac the name “Newport of the West.”

In the 1870s, most towns up and down the Mississippi Valley welcomed the railroad. But when the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul, and Pacific Railway approached Garrard to buy land for a line linking Lake City and Red Wing, Garrard refused. He wouldn’t allow the noise and dirt into his village. Instead, he donated land for tracks and a depot three miles from town. Growing numbers of passengers arrived at the new depot, known as “Frontenac Station,” and rode by horse and buggy to “Old Frontenac.” Thirty years later, automobiles and hard-surfaced highways cut into train travel while encouraging hikers, boaters, and picnickers.

During the Great Depression, when President Roosevelt’s New Deal funded construction of hundreds of national and state parks, Frontenac was identified for state park status. The property met the criteria of providing historic and cultural significance, natural attractions, and recreational potential. Efforts failed, however, when federal officials decided the area lacked sufficient personnel and resources to support a Civilian Conservation Corps camp.

Over the next twenty years, state park status was reconsidered multiple times, but approval repeatedly failed. Ultimately, it took a grassroots effort to move the project forward. In the mid-1950s members of the Hiawatha Valley Association, a business organization promoting tourism along the Upper Mississippi Valley, joined forces with the state’s park and conservation officials to advance a plan for a 500-acre park at the Frontenac location. To demonstrate local support, a group of citizens formed the Frontenac State Park Association. Members lobbied legislators, raised funds, and solicited donations of property for the park. Although approval remained contentious up to the final vote, the park was approved by the 1957 Minnesota legislature.

Bibliography

Alsen, Ken. Old Frontenac, Minnesota: Its History and Architecture. History Press, 2011.

Anfinson, John O. River of History: A Historic Resources Study of the Mississippi National River and Recreation Area. National Park Service and United States Army Corps of Engineers. St. Paul District, 2003.

https://www.nps.gov/miss/learn/historyculture/historic_resources.htm

Bergey, Ben. Frontenac State Park: Management Plan Amendment. Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, 2022. https://files.dnr.state.mn.us/input/mgmtplans/parks/frontenac/frontenac-plan-amend-2022.pdf

Densmore, Frances. “The Garrard Family in Frontenac.” Minnesota History 14, no. 1 (March 1933): 31–43.

https://storage.googleapis.com/mnhs-org-support/mn_history_articles/14/v14i01p031-043.pdf

Folwell, William Watts. A History of Minnesota, vol. 1. Minnesota Historical Society, 1921.

https://archive.org/details/historyofminneso01folwuoft

“Frontenac Park Meeting Planned.” Winona Daily News, June 2, 1954.

“Funds Granted for Recreation Plans in State.” St. Cloud Times, January 26, 1935.

Gaster, Jake (Frontenac State Park Manager). Interview with the author. Frontenac State Park, June 17, 2024.

Goodhouse, Dakota. “Iŋyaŋ Tiyopa (Stone Door).” In “Makȟóčhe Wašté, The Beautiful Country: A Lakota Landscape Map.”

https://drive.google.com/open?id=1pbLuALDtMHbxpigEh28R_6KZXdyPj1X-

Meyer, Roy W. Everyone’s Country Estate: A History of Minnesota’s State Parks. Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1991.

Nelson, Sharon N. Frontenac Station: The Early Years. Self-published, 2015.

Petersen, William J. “The ‘Virginia’: The ‘Clermont’ of the Upper Mississippi.” Minnesota History 9, no. 4 (December 1928): 347–362.

https://storage.googleapis.com/mnhs-org-support/mn_history_articles/9/v09i04p347-362.pdf

“State Selects Old Frontenac for New Park.” Winona Daily News, May 5, 1954.

Tweet, Roald. History of Transportation on the Upper Mississippi and Illinois Rivers. National Waterways Study, US Army Engineer Water Resources Support Center, Institute for Water Resources, 1983.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/History_of_Transportation_on_the_Upper_M/oUlZ6YYsEI4C

Related Resources

Primary

Lutz, Thomas. “Old Frontenac Historic District Additional Documentation.” National Register of Historic Places registration form, March 21, 1973.

https://catalog.archives.gov/id/93200431

Secondary

Blegen, Theodore C. “The ‘Fashionable Tour’ on the Upper Mississippi.” Minnesota History 20, no. 4 (December 1939) 377–396.

https://storage.googleapis.com/mnhs-org-support/mn_history_articles/20/v20i04p377-396.pdf

Fowler, Russell. “Justice on the Mississippi: The Golden Age of Steamboats.” Tennessee Bar Association 60, no. 1 (January/February 2024).

https://www.tba.org/?pg=Articles&blAction=showEntry&blogEntry=101024

Hall, Ted. Growing with the Grass. Rainy Lake Printing House, 1992.

Swanholm, Marx, and Susan Zeik. “The Tonic of Wildness: The Golden Age of the “Fashionable Tour” on the Upper Mississippi.” Historic Fort Snelling Chronicles, vol. 3. Minnesota Historical Society, 1976.

Related Images

View from Frontenac State Park

Lakeside Hotel, Frontenac

Holding Location

Articles

Crag on Point-No-Point Bluff at Frontenac

Holding Location

Articles

People wading at Frontenac Beach

Holding Location

Articles

View of Lake Pepin from Frontenac

Holding Location

Articles

Shoreline of Lake Pepin at Frontenac

Holding Location

Articles

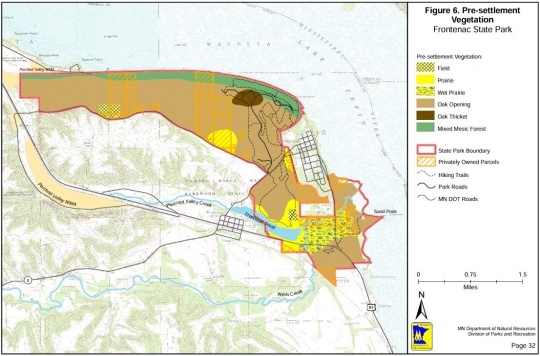

Map of pre-settlement vegetation at Frontenac State Park

Public domain

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

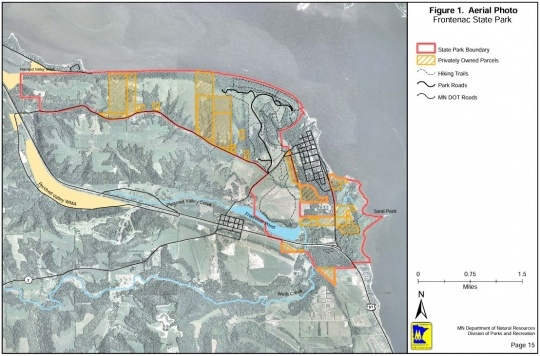

Labeled aerial photo of Frontenac State Park

Public domain

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

Iŋyaŋ Tiyopa (Stone Door)

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

Lake Pepin viewed from inside Frontenac State Park

All rights reserved

Articles

Field inside Frontenac State Park

All rights reserved

Articles

Road through Frontenac State Park

All rights reserved

Articles

Road through Frontenac State Park in winter

All rights reserved

Articles

Winter sunset in Frontenac State Park

All rights reserved

Articles

Bench at an overlook point in Frontenac State Park

All rights reserved

Articles

Lake Pepin in winter

All rights reserved

Articles

Woods inside Frontenac State Park

All rights reserved

Articles

Spotted sandpiper on Lake Pepin

All rights reserved

Articles

Related Articles

Turning Point

In 1871, Israel Garrard refuses to allow the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul, and Pacific Railway to lay track within the town of Frontenac. Instead, Garrard and the railroad agree to construct a new village three miles west of the old town. The new Frontenac Station becomes the commercial center for the area. The original townsite and Garrard’s hunting and recreational acreage remained largely unchanged over the next century, preserving the historic and cultural significance of the area.

Chronology

10,000 years ago

400–500 BCE

1600 CE

1727

1823

1837

1849

mid-1850s

1859

1868

1935

1954

1957

1961

1973

1975

2020

Bibliography

Alsen, Ken. Old Frontenac, Minnesota: Its History and Architecture. History Press, 2011.

Anfinson, John O. River of History: A Historic Resources Study of the Mississippi National River and Recreation Area. National Park Service and United States Army Corps of Engineers. St. Paul District, 2003.

https://www.nps.gov/miss/learn/historyculture/historic_resources.htm

Bergey, Ben. Frontenac State Park: Management Plan Amendment. Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, 2022. https://files.dnr.state.mn.us/input/mgmtplans/parks/frontenac/frontenac-plan-amend-2022.pdf

Densmore, Frances. “The Garrard Family in Frontenac.” Minnesota History 14, no. 1 (March 1933): 31–43.

https://storage.googleapis.com/mnhs-org-support/mn_history_articles/14/v14i01p031-043.pdf

Folwell, William Watts. A History of Minnesota, vol. 1. Minnesota Historical Society, 1921.

https://archive.org/details/historyofminneso01folwuoft

“Frontenac Park Meeting Planned.” Winona Daily News, June 2, 1954.

“Funds Granted for Recreation Plans in State.” St. Cloud Times, January 26, 1935.

Gaster, Jake (Frontenac State Park Manager). Interview with the author. Frontenac State Park, June 17, 2024.

Goodhouse, Dakota. “Iŋyaŋ Tiyopa (Stone Door).” In “Makȟóčhe Wašté, The Beautiful Country: A Lakota Landscape Map.”

https://drive.google.com/open?id=1pbLuALDtMHbxpigEh28R_6KZXdyPj1X-

Meyer, Roy W. Everyone’s Country Estate: A History of Minnesota’s State Parks. Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1991.

Nelson, Sharon N. Frontenac Station: The Early Years. Self-published, 2015.

Petersen, William J. “The ‘Virginia’: The ‘Clermont’ of the Upper Mississippi.” Minnesota History 9, no. 4 (December 1928): 347–362.

https://storage.googleapis.com/mnhs-org-support/mn_history_articles/9/v09i04p347-362.pdf

“State Selects Old Frontenac for New Park.” Winona Daily News, May 5, 1954.

Tweet, Roald. History of Transportation on the Upper Mississippi and Illinois Rivers. National Waterways Study, US Army Engineer Water Resources Support Center, Institute for Water Resources, 1983.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/History_of_Transportation_on_the_Upper_M/oUlZ6YYsEI4C

Related Resources

Primary

Lutz, Thomas. “Old Frontenac Historic District Additional Documentation.” National Register of Historic Places registration form, March 21, 1973.

https://catalog.archives.gov/id/93200431

Secondary

Blegen, Theodore C. “The ‘Fashionable Tour’ on the Upper Mississippi.” Minnesota History 20, no. 4 (December 1939) 377–396.

https://storage.googleapis.com/mnhs-org-support/mn_history_articles/20/v20i04p377-396.pdf

Fowler, Russell. “Justice on the Mississippi: The Golden Age of Steamboats.” Tennessee Bar Association 60, no. 1 (January/February 2024).

https://www.tba.org/?pg=Articles&blAction=showEntry&blogEntry=101024

Hall, Ted. Growing with the Grass. Rainy Lake Printing House, 1992.

Swanholm, Marx, and Susan Zeik. “The Tonic of Wildness: The Golden Age of the “Fashionable Tour” on the Upper Mississippi.” Historic Fort Snelling Chronicles, vol. 3. Minnesota Historical Society, 1976.