Henry Longstreet Taylor was a key figure in the development of tuberculosis treatment in Minnesota. The sanatoriums he helped establish in the early 1900s were an essential part of a statewide anti-tuberculosis campaign to control and study the disease.

Taylor was born in Cincinnati, Ohio, on August 14, 1857. He graduated from Haverford College in Pennsylvania and received his doctor of medicine degree from the College of Ohio in 1882. After graduation, he went to Europe to study with Robert Koch, who had identified the bacillus that caused tuberculosis. Four years later, Taylor returned to the United States intending to establish a medical practice in Ohio. Illness caused him to move to Asheville, North Carolina. He recovered and worked for four years at an Asheville sanatorium.

Taylor came to Minnesota in 1893 because he knew that tuberculosis was a public health menace in the state. At that time, there was no cure for the disease. Some doctors believed that people who were sick with tuberculosis could get well if they were given enough rest, fresh air, and good food.

Taylor wanted to provide places for tuberculous people to take the fresh-air cure. In 1899, he erected tents in a field near the Ramsey County Poor Farm so invalids could live outdoors during the summer. Because tuberculosis was contagious, neighbors of the Poor Farm did not want the tents near them. The next year, they plowed the fields and planted potatoes. Taylor abandoned that project and began to campaign for sanatorium construction for people with tuberculosis.

Taylor delivered speeches and wrote articles to promote the sanatorium concept throughout Minnesota. In 1901, the state legislature created a three-member commission to study the need for a state-operated sanatorium. Taylor was appointed chair of the commission. Its members visited many sanatoriums in the United States. They also looked at potential locations in Minnesota. Their final report recommended that a state sanatorium be built by Leech Lake in Cass County near Walker. The legislature provided funding to purchase the land. There was not enough money to start construction.

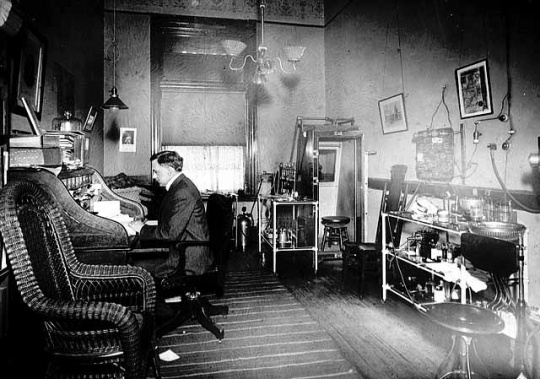

Taylor became impatient with the delay in sanatorium building. He worked with other doctors to establish places for people to heal. In 1902, he helped physicians at City and County Hospital in St. Paul create a separate tuberculosis ward. The next year, he was given the use of an entire floor at Luther Hospital for his patients. In 1905, he used private financial support to build his own sanatorium on Lake Pokegama near Pine City.

The Minnesota State Sanatorium for Consumptives finally opened in December 1907. Taylor realized that the needs of many people could not be met by so few institutions. In 1910, he helped open Cuenca Sanatorium on Bass Lake (later renamed Lake Owasso). In 1915, he oversaw the opening of the Ramsey County’s Children’s Preventorium on the same site. As its medical director, he worked to improve the health of children who were at risk for developing tuberculosis.

In 1912, Taylor was appointed to a legislative commission to develop a system for creating county sanatorium districts. By 1918, Minnesota had fourteen county sanatoriums. It offered tuberculosis treatment to more of its citizens than any other state.

Taylor’s efforts at tuberculosis control and education were not limited to sanatoriums. In 1920, he endowed a Pokegama Scholarship for Research in Tuberculosis at the University of Minnesota. He also served on the boards of several local, state, and national tuberculosis associations, including the Minnesota Public Health Association and the National Tuberculosis Association.

Taylor died on January 2, 1932, just weeks after helping with the Ramsey County Christmas Seal campaign. In 1906, 2,042 people had died from the disease statewide. In 1932, thanks in part to Taylor’s work, half as many citizens died of tuberculosis, even though there was still no cure.