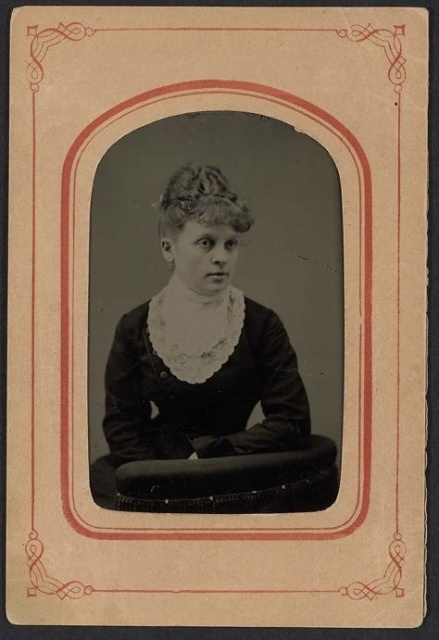

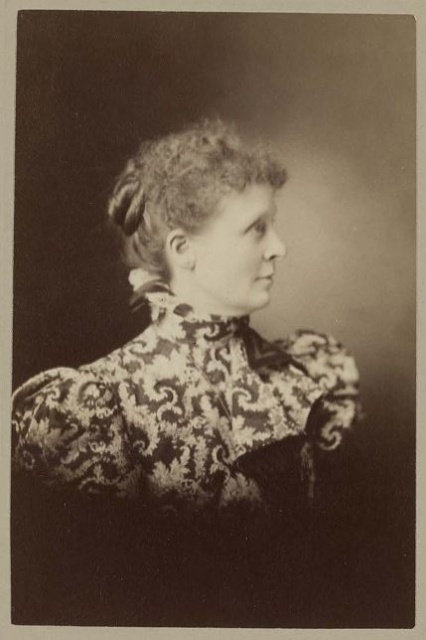

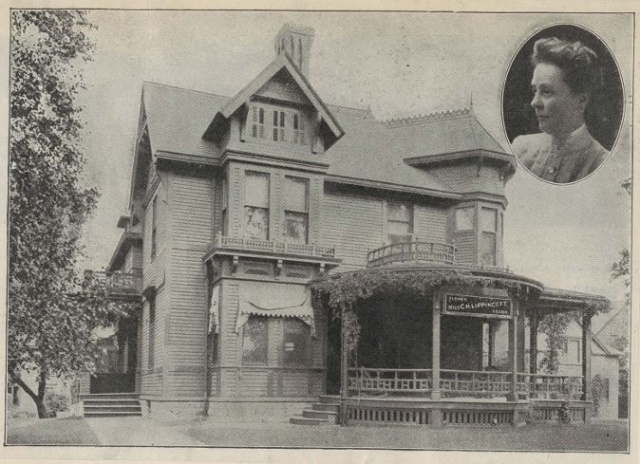

In 1887, Carrie H. Lippincott was a twenty-seven-year-old New Jersey native with an eighth-grade education. She moved to Minnesota, where she created a mail-order company focused on selling flower seeds to women. Lippincott established herself in her new home by practicing innovative marketing methods and developing what we might call today a personal brand, declaring herself “The Pioneer Seedswoman of America.”

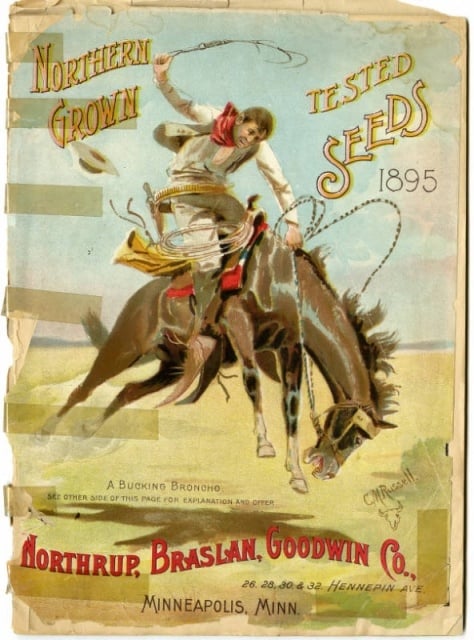

When Lippincott arrived in Minneapolis in the late 1880s, she turned to her brother-in-law, Samuel Y. Haines, for advice on finding a job. Haines, who was working for the Minneapolis seed house Braslan, Northrup, Goodwin and Company (later renamed Northrup, King and Company), encouraged her to follow his example and sell seeds. He assured her that the nation’s rapidly expanding mail-order business had room for a woman “with the nerve to advertise and the knowledge to fill her orders satisfactorily.”

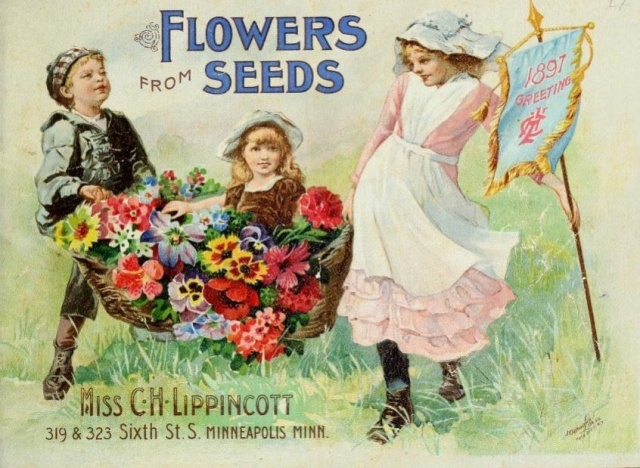

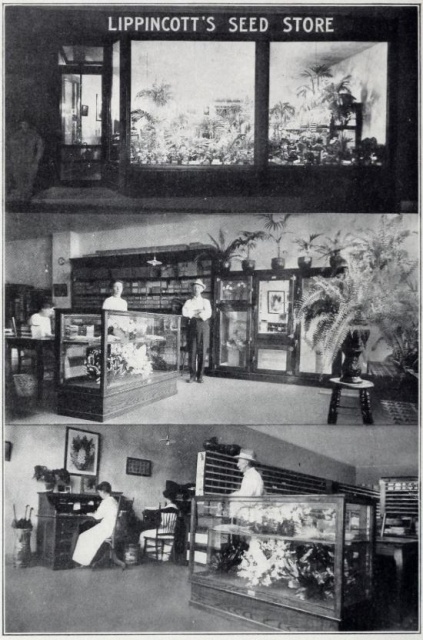

Lippincott took Haines’ advice and worked side-by-side with him for a few years, learning the seed business and mapping sales strategies for an audience of women. She launched her business in 1891 under the name “Miss C. H. Lippincott.” That first year, she filled 6,000 orders. In 1894, she tallied 100,000.

Lippincott’s mail-order marketing plan began each January with the release of a new catalog. At five by seven inches, her publications were half the size of most seed catalogs and designed to appeal to women. Cover art featured cherubic children and an abundance of flowers. Inside, pages offered instructions on cultivating seeds, with hints on how and where each variety might thrive.

Her next step was to post advertisements in magazines and newspapers. Although the ads were small, they were conspicuous, typically positioned at the top or side columns of the page. The ads were not intended to secure a sale; they were an invitation to send for a free catalog. With catalogs in buyers’ hands, Lippincott used upselling methods to boost sales. Prices were just pennies a seed packet, but orders could be bumped up to qualify for free gifts. Her 1894 catalog offered fifteen cents’ worth of free seeds on orders totaling fifty cents. Costlier purchases earned more seeds or a rose plant. Every customer could request Lippincott’s free booklet Floral Culture, with its detailed instructions for growing hundreds of flower strains.

Lippincott constructed a loyal community. Most years, she placed a friendly greeting in her catalogs with updates on the Lippincott family and her company. By 1896, she was receiving 150,000 orders a year from customers in Japan, India, and South Africa as well as Minnesota. She expanded her inventory based on customers’ requests, adding vines and more roses to her stock in 1903 and vegetable seeds in 1907.

Lippincott’s success drew competition from other Minnesota entrepreneurs, including women with connections to established seed companies. In the mid-1890s, Jessie R. Prior took over the flower sales for her husband’s seed store, marketing herself as “Seedswoman.” A year later, a local florist, E. Nagel and Company, passed its flower seed business to Emma V. White, the “Northstar Seedswoman.”

Lippincott’s most challenging rival, however, turned out to be her brother-in-law. In 1898 Haines filed a lawsuit against her, claiming rights to half the ownership of the C. H. Lippincott seed company. He claimed to be a partner in the business; she protested that the business that bore her name was hers alone. The case was dismissed when Lippincott and Haines agreed to divide the company’s assets equally. Lippincott quickly started over, releasing an 1899 catalog just weeks after the dissolution.

Lippincott continued her mail-order sales for another twenty years. During World War I, she echoed the nation’s call for Liberty Gardens and offered a vegetable seed collection for twenty-five cents. She called on her customers to order seeds carefully and waste nothing while still planting flowers to provide beauty in troubled times. She continued to live in Minneapolis until her death, at age eighty-one, in 1941.

The last of Lippincott’s seed catalogs was published in 1918, but her catalogs and seed packets have become Americana collectibles. They are preserved in numerous university and state library archives, including the University of Minnesota’s Andersen Horticultural Library and the Biodiversity Heritage Library, headquartered at the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives in Washington, DC.