Topics

Category

Era

Lindbergh, Charles A. (1902–1974)

Charles A. Lindbergh, a native of Little Falls, became a world-famous aviator after completing the first nonstop, solo transatlantic flight in May 1927. Although his flying feats made him an American cultural hero in the 1920s, his links to Nazism, support for eugenics, and publicly unacknowledged children in Germany tarnished his legacy in the decades that followed.

Charles Augustus Lindbergh was born in Detroit, Michigan, in 1902. He grew up outside Little Falls on a 110-acre farm on the banks of the Mississippi River. Though they never divorced, Lindbergh’s parents, Charles August (C. A.) and Evangeline, were estranged. After the complete loss of their home to fire in 1905, they lived in separate homes.

The Lindberghs built a smaller home on the original’s foundation. It became a summer residence for Lindbergh and his mother, who traveled to Washington, D.C., each winter for ten years following C. A. Lindbergh’s election to the U.S. House of Representatives. Charles Lindbergh attended college at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, in fall 1920. After three semesters, he was dropped from the program and enrolled at the Nebraska Aircraft Corporation's flying school. He spent time on the barnstorming circuit before purchasing his first plane, a Curtiss JN4-D, commonly called a “Jenny.”

In 1924, Lindbergh enrolled in Army Flying School, where he graduated at the top of his class. Following graduation, Lindbergh went to Lambert Field in St. Louis, Missouri. There, he accepted a job with the Robertson Aircraft Corporation as chief pilot for the soon-to-be-awarded St. Louis–Chicago airmail route.

In 1919, a French businessman, Raymond Orteig, offered a $25,000 prize to the first team to fly nonstop between New York, New York, and Paris, France. After learning of the prize, Lindbergh began to plan a flight to Paris. Lindbergh discussed his idea with St. Louis businessmen and aviation supporters who pooled their resources to provide Lindbergh with the funding to purchase an airplane that could make the transatlantic flight.

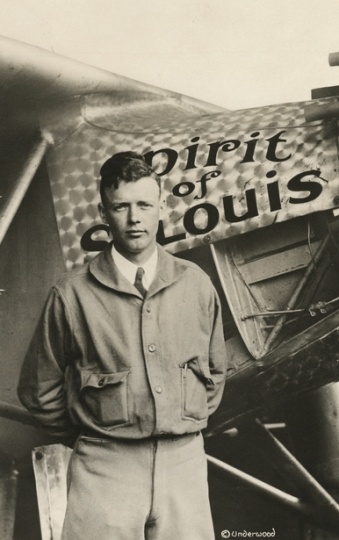

Ryan Aeronautical Company in San Diego, California, built the Spirit of St. Louis—a single-engine monoplane powered by a Wright Whirlwind J-5C engine—for $10,580. Lindbergh worked alongside the designer and the construction crew.

By the time Lindbergh was ready for his flight, six well-known aviators had already lost their lives in pursuit of the Orteig Prize. Undaunted, Lindbergh set out to break the record on May 20, 1927. At 7:52 a.m., after loading the plane with 450 gallons of gasoline, Lindbergh climbed into the cockpit and gave the go ahead to takeoff. Thirty-three and one-half hours later, he landed at Le Bourget Field, just outside of Paris.

Upon returning home, Lindbergh continued to promote aviation by touring the United States, Central and South America. When he was in Mexico he met Anne Morrow, the daughter of the U.S. Ambassador. They married in 1929.

Tragedy struck the Lindberghs in March 1932 when their first-born son, twenty-month-old Charlie, was kidnapped from the family's home in New Jersey. The child’s body was found two months after he was taken. Bruno Richard Hauptmann was arrested for the crime in 1934 and convicted the following year. It was around this time that Lindbergh began to support eugenics, a racist doctrine committed to eliminating human populations judged to be “inferior.”

In 1936, an American military attaché invited Lindbergh to Germany to help gather intelligence about the Third Reich. At a dinner in Berlin, German Air Minister Hermann Göring surprised Lindbergh with an award for his services to aviation. Many saw Lindbergh’s acceptance of the "Nazi medal" as a sign of his sympathies with the Third Reich, and he praised the Nazi government even as it persecuted Jewish people in the years before World War II. In 1941, he made speeches on behalf of the America First Committee, a nationwide organization that opposed American intervention in the war. The press and many members of the public accused Lindbergh of injecting anti-Semitism into his argument for neutrality, a claim that he denied.

After the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Lindbergh did what he could to help the Allies. In 1944, he persuaded United Aircraft to designate him a technical representative in the South Pacific to study aircraft performances under combat conditions. Despite being a civilian, Lindbergh participated in fifty combat missions.

Following World War II, Lindbergh served on the board of directors for Pan American Airways and developed a passion for protecting the environment. He wrote The Spirit of St. Louis, which was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for autobiography in 1954.

Beginning in the late 1950s, Lindbergh had children (seven in total) with three different women in Germany. He kept their existence a secret for the rest of his life, and died in Hawaii on August 26, 1974.

Bibliography

Berg, A. Scott. Lindbergh. New York: Berkley Books, 1998.

Friedman, David M. The Immortalists: Charles Lindbergh, Dr. Alexis Carrel, and Their Daring Quest to Live Forever. Ecco/HarperCollins, 2007.

Lindbergh: Fallen Hero. American Experience.

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/lindbergh-fallen-hero

Lindbergh, Charles A. Boyhood on the Upper Mississippi. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1974. Reprinted as Lindbergh Looks Back, Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2002.

——— . The Spirit of St. Louis. New York: Scribner, 1953.

Lindbergh’s Double Life. Charles Lindbergh House and Museum. Minnesota Historical Society.

https://www.mnhs.org/lindbergh/learn/family/double-life

Related Resources

Primary

Charles A. Lindbergh and family papers, 1808–1987

Manuscript Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/P1675.xml

Description: The papers of Charles Augustus Lindbergh document his high school, university, and aeronautical education; his early career in aviation (1925–1927); the 1927 transatlantic solo flight; his advocacy of neutrality in the years preceding the United States' entry into World War II; his recollections (1969) of his childhood; and remarks (1968–1969) about his biographies.

Lindbergh, Anne Morrow. Bring Me A Unicorn: Diaries and Letters of Anne Morrow Lindbergh, 1922–1928. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1971.

——— . Hour of Gold, Hour of Lead: Diaries and Letters of Anne Morrow Lindbergh, 1929–1932. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1973.

——— . Locked Rooms and Open Doors: Diaries and Letters of Anne Morrow Lindbergh, 1933–1935. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1974.

——— . The Flower and the Nettle: Diaries and Letters of Anne Morrow Lindbergh, 1936–1939. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1976.

——— . War Within and Without: Diaries and Letters of Anne Morrow Lindbergh, 1939–1944. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1980.

——— . Against Wind and Tide: Diaries and Letters of Anne Morrow Lindbergh, 1947–1986. Edited by Reeve Lindbergh. New York: Pantheon, 2012.

Lindbergh, Charles A. Autobiography of Values. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1978.

——— . The Wartime Journals of Charles A. Lindbergh. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc., 1970.

——— . “We.”: The Famous Flier’s Own Story of His Life and His Transatlantic Flight, Together with His Views on the Future of Aviation. New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1927.

Lindbergh, Reeve. Under A Wing: A Memoir. New York: Delta Books, 1998.

——— . Forward From Here: Leaving Middle Age—and Other Unexpected Adventures. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2008.

Secondary

Allard, Noel, and Gerald Sandvick. Minnesota Aviation History, 1857–1945. Chaska, MN: MAHB, 1993.

Cole, Wayne S. Charles A. Lindbergh and the Battle Against American Intervention in World War II. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1974.

Gardner, Lloyd C. The Case That Never Dies: The Lindbergh Kidnapping. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2004.

Mosley, Leonard. Lindbergh: A Biography. Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company, 1976.

Web

Charles A. Lindbergh House and Museum. https://www.mnhs.org/lindbergh

Related Images

Colonel Charles Augustus Lindbergh

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

Evangeline Lindbergh with her son Charles Augustus Lindbergh

Public domain

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

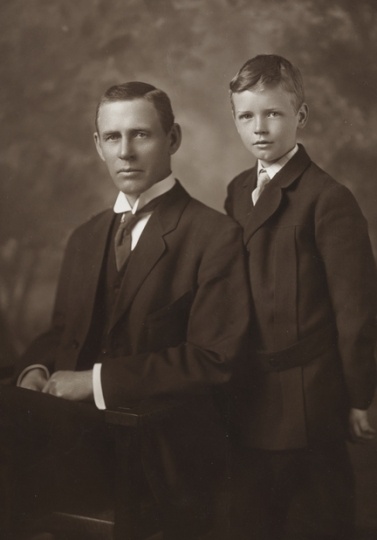

Charles August Lindbergh with his son Charles Augustus Lindbergh

Charles August Lindbergh with his son, Charles Augustus Lindbergh, ca. 1910, when the father was about fifty-one years old and his son was about eight years old. Note the difference in their middle names. The elder Lindbergh is most often referred to as "Sr."

Holding Location

Charles August Lindbergh with his son Charles Augustus Lindbergh on a hunting expedition

Public domain

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

Charles Lindbergh with his dog Dingo

Charles Lindbergh with his dog Dingo, c.1912.

Public domain

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

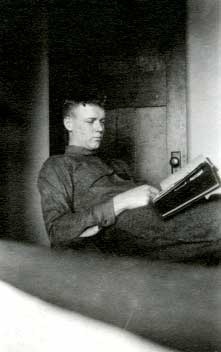

Charles Augustus Lindbergh and his photo album, Madison, Wisconsin

Public domain

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

Second Lieutenant Charles Augustus Lindbergh

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

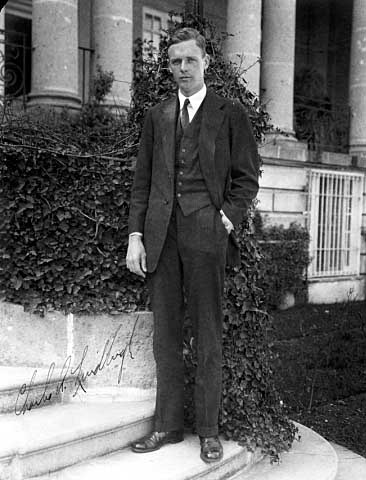

Charles Augustus Lindbergh with his plane

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

Charles Lindbergh with “Spirit of St. Louis”

Holding Location

More Information

Charles Augustus Lindbergh

Holding Location

More Information

Charles Lindbergh with the "Spirit of St. Louis"

Charles Augustus Lindbergh with the "Spirit of St. Louis," c.1927.

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

Charles Augustus Lindbergh standing in front of the "Spirit of St. Louis"

Charles Augustus Lindbergh with the "Spirit of St. Louis," c.1928.

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

Charles Augustus Lindbergh and pilots in Detroit

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

Charles and Anne Lindbergh in flight suits

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

Charles Augustus Lindbergh testifying at the Air Mail Hearing

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

Charles Augustus Lindbergh with Tommy McGuire in the South Pacific

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

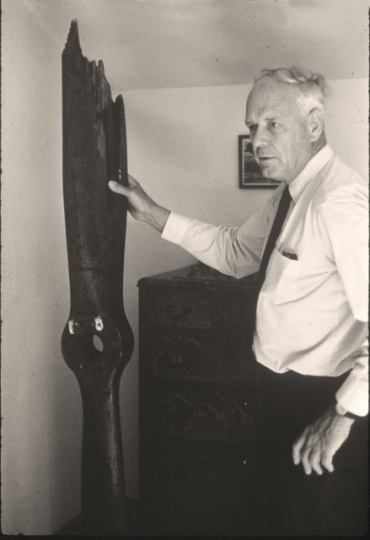

Charles Augustus Lindbergh with a plane propeller

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

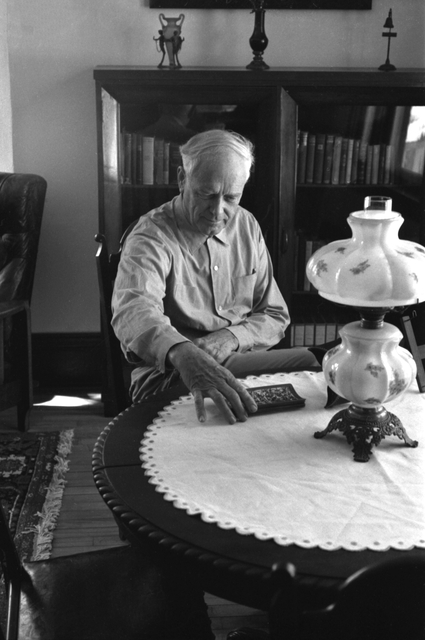

Charles Lindbergh in the living room of his restored boyhood home

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

Related Articles

Turning Point

In May 1927, Charles A. Lindbergh completes the first nonstop, solo transatlantic flight between New York City and Paris, France, advancing the field of aviation.

Chronology

1902

1922

1927

1929

1932

1935

1938

1941

1941

1944

1954

1964

1973

1974

2003

Bibliography

Berg, A. Scott. Lindbergh. New York: Berkley Books, 1998.

Friedman, David M. The Immortalists: Charles Lindbergh, Dr. Alexis Carrel, and Their Daring Quest to Live Forever. Ecco/HarperCollins, 2007.

Lindbergh: Fallen Hero. American Experience.

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/lindbergh-fallen-hero

Lindbergh, Charles A. Boyhood on the Upper Mississippi. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1974. Reprinted as Lindbergh Looks Back, Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2002.

——— . The Spirit of St. Louis. New York: Scribner, 1953.

Lindbergh’s Double Life. Charles Lindbergh House and Museum. Minnesota Historical Society.

https://www.mnhs.org/lindbergh/learn/family/double-life

Related Resources

Primary

Charles A. Lindbergh and family papers, 1808–1987

Manuscript Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/P1675.xml

Description: The papers of Charles Augustus Lindbergh document his high school, university, and aeronautical education; his early career in aviation (1925–1927); the 1927 transatlantic solo flight; his advocacy of neutrality in the years preceding the United States' entry into World War II; his recollections (1969) of his childhood; and remarks (1968–1969) about his biographies.

Lindbergh, Anne Morrow. Bring Me A Unicorn: Diaries and Letters of Anne Morrow Lindbergh, 1922–1928. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1971.

——— . Hour of Gold, Hour of Lead: Diaries and Letters of Anne Morrow Lindbergh, 1929–1932. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1973.

——— . Locked Rooms and Open Doors: Diaries and Letters of Anne Morrow Lindbergh, 1933–1935. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1974.

——— . The Flower and the Nettle: Diaries and Letters of Anne Morrow Lindbergh, 1936–1939. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1976.

——— . War Within and Without: Diaries and Letters of Anne Morrow Lindbergh, 1939–1944. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1980.

——— . Against Wind and Tide: Diaries and Letters of Anne Morrow Lindbergh, 1947–1986. Edited by Reeve Lindbergh. New York: Pantheon, 2012.

Lindbergh, Charles A. Autobiography of Values. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1978.

——— . The Wartime Journals of Charles A. Lindbergh. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc., 1970.

——— . “We.”: The Famous Flier’s Own Story of His Life and His Transatlantic Flight, Together with His Views on the Future of Aviation. New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1927.

Lindbergh, Reeve. Under A Wing: A Memoir. New York: Delta Books, 1998.

——— . Forward From Here: Leaving Middle Age—and Other Unexpected Adventures. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2008.

Secondary

Allard, Noel, and Gerald Sandvick. Minnesota Aviation History, 1857–1945. Chaska, MN: MAHB, 1993.

Cole, Wayne S. Charles A. Lindbergh and the Battle Against American Intervention in World War II. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1974.

Gardner, Lloyd C. The Case That Never Dies: The Lindbergh Kidnapping. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2004.

Mosley, Leonard. Lindbergh: A Biography. Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company, 1976.

Web

Charles A. Lindbergh House and Museum. https://www.mnhs.org/lindbergh