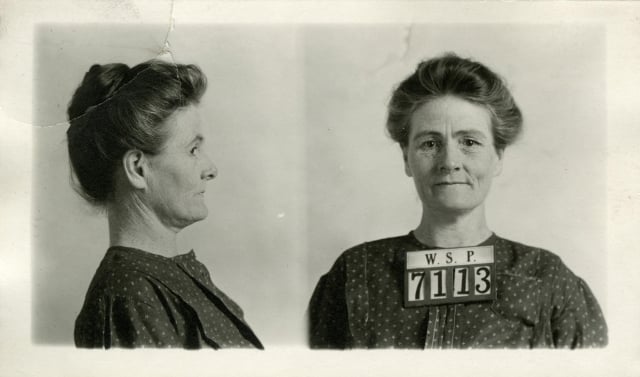

In 1914 Linda Burfield Perry Hazzard’s unconventional healing methods landed her in prison in Washington State for manslaughter. Despite minimal medical training, she styled herself as a physician and for more than thirty years promoted healing through fasting, killing as many as fifteen people. Most of her victims died in Washington, but this Minnesota native developed her craft, and took her first victim, in Minneapolis.

Linda Laura Burfield was the first of seven children born to Montgomery Burfield and the former Susan O’Neil, in Carver County, Minnesota, in 1867. At age eighteen she married Erwin Perry, owner of a livery business in Fergus Falls. They moved to Minneapolis in 1897 and separated soon thereafter.

Burfield Perry wrote that in her youth her father employed a physician to give the children an annual dose of a mercury-based anti-parasitic that left her with chronic digestive troubles. In 1898, at the age of thirty-one, she learned of the works of Dr. Edward H. Dewey, author of The No-Breakfast Plan and Fasting-Cure, a book that advocated for fasting as a way to allow the body to heal itself. She tried it, with success, and soon put herself (she claimed) under his care.

Even before encountering Dr. Dewey’s work, Burfield Perry had been studying osteopathy, a branch of medicine that emphasized the manipulation of the body more than the use of medicines. By 1901 she had set up her own, unlicensed medical practice, under the name Dr. Linda Burfield Perry. She advertised treatment of “all nervous diseases, liquor habit, vices; painless childbirth.” In this era before antibiotics, even the best physicians had few tools to cure disease; most patients got well, or not, on their own. With cures elusive, and people often desperate, methods that would later be rejected were accepted by the public. Burfield Perry’s practice grew; she claimed later that over a ten-year period she had treated more than a thousand patients.

In the fall of 1902 Gertrude Young of Minneapolis came her way seeking relief from partial paralysis. On about October 1 of that year she began a forty-day fast that she did not complete; Young died November 19. After an autopsy, the coroner, Dr. U. G. Williams, ruled the cause exhaustion brought on by starvation. But the death certificate lists the cause as “paralysis.”

Dr. Williams demanded an investigation. The Hennepin County attorney, Frederick Boardman, found no ground for criminal prosecution: There was no law against advising a person not to eat, and Young’s fast had been voluntary. The death did not discourage Burfield Perry. In 1903 she appeared, now as simply Dr. Linda Burfield (she and Erwin Perry had divorced), in a full-page newspaper ad under the banner, “Prominent Osteopathic Physicians.” Her ad read, “Fasting Is Nature’s Remedy.”

In 1906 she and her second husband, Samuel Hazzard, left Minnesota for Seattle, where she soon attracted a following. She established a clinic called Wilderness Heights in nearby Olalla, Washington. There, between 1908 and 1913, as many as fifteen people died while under her care. She had acquired a medical license in Washington, which gave prosecutors a weapon they lacked in Minnesota. In 1911 Dr. Hazzard, as she was known there, was charged with first-degree murder in the death of a wealthy heiress, Claire Williamson, who had dwindled to fifty pounds in Hazzard’s care. Convicted only of manslaughter, she got a sentence of five-to-twenty years. Her appeals took up most of the next two years, during which time her clinic thrived. She went to prison in January 1914, defiant: “ This will not be a painful departure, but, rather, a triumphal progress.”

She served two years, received a pardon, practiced medicine in New Zealand, and returned to Washington in 1919. Though she now lacked a medical license, she rebuilt her clinic and practice, calling it a health school. A fire destroyed the clinic in 1935. She died three years later, while fasting. It was said that she starved herself to death, but she would have disagreed. In her first book, Fasting For the Cure of Disease, she had written that “it is questionable whether, in a conscious being, death has ever resulted from starvation.”