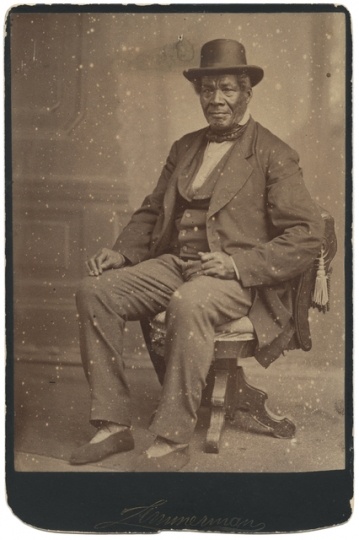

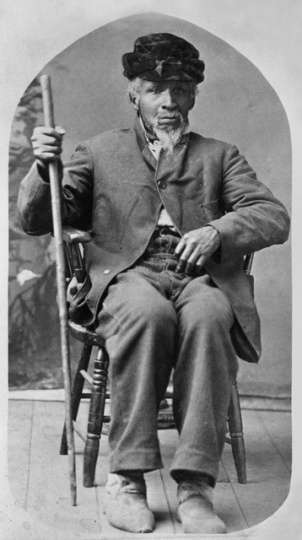

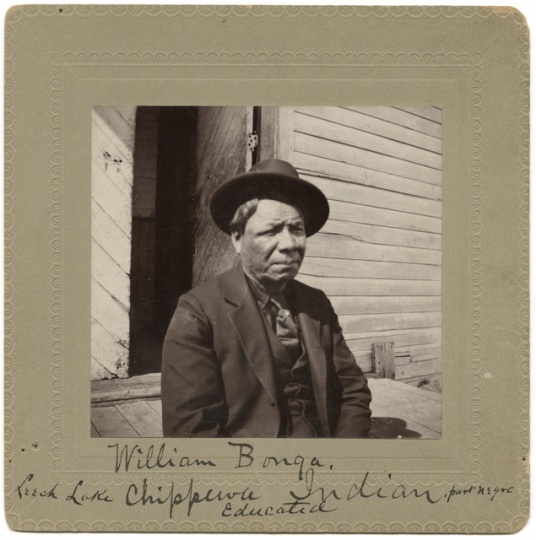

Bonga, George (ca. 1802–1874)

Bibliography

Bergin, Daniel Pierce. "This is His Place: George Bonga." In North Star: Minnesota's Black Pioneers. DVD. St. Paul: Twin Cities Public Television, 2004.

Bonga, George. "The Letters of George Bonga." Journal of Negro History 12, no. 1 (January 1927): 41–54.

Green, William D. A Peculiar Imbalance: The Fall and Rise of Racial Equality in Early Minnesota." St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 2007.

Katz, William Loren. Black Indians: A Hidden Heritage. New York: Athaneum, 1986.

McWatt, Arthur C. Crusaders for Justice: A Chronicle of Protest by Agitators, Advocates, and Activists in their Struggle for Human Rights in St. Paul, Minnesota, 1802–1985. Brooklyn Park: Papyrus Publishing Inc., 2009.

White, Bruce M. "The Power of Whiteness: Or, the Life and Times of Joseph Rolette, Jr." Minnesota History 56, no. 4 (Winter 1998/1999): 178–197.

http://collections.mnhs.org/mnhistorymagazine/articles/56/v56i04p178-197.pdf

Chronology

1802

1820

1837

1842

1856

1867

1874

Bibliography

Bergin, Daniel Pierce. "This is His Place: George Bonga." In North Star: Minnesota's Black Pioneers. DVD. St. Paul: Twin Cities Public Television, 2004.

Bonga, George. "The Letters of George Bonga." Journal of Negro History 12, no. 1 (January 1927): 41–54.

Green, William D. A Peculiar Imbalance: The Fall and Rise of Racial Equality in Early Minnesota." St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 2007.

Katz, William Loren. Black Indians: A Hidden Heritage. New York: Athaneum, 1986.

McWatt, Arthur C. Crusaders for Justice: A Chronicle of Protest by Agitators, Advocates, and Activists in their Struggle for Human Rights in St. Paul, Minnesota, 1802–1985. Brooklyn Park: Papyrus Publishing Inc., 2009.

White, Bruce M. "The Power of Whiteness: Or, the Life and Times of Joseph Rolette, Jr." Minnesota History 56, no. 4 (Winter 1998/1999): 178–197.

http://collections.mnhs.org/mnhistorymagazine/articles/56/v56i04p178-197.pdf