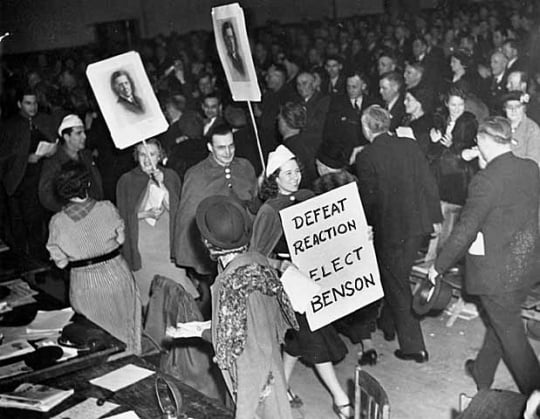

Elmer Benson was elected in 1936 as Minnesota’s second Farmer-Labor Party governor with over 58 percent of the vote. He was defeated only two years later by an even larger margin. An outspoken champion of Minnesota’s workers and family farmers, Benson lacked the political gifts of his charismatic predecessor, Floyd B. Olson. However, many of his proposals—at first considered radical—became law in the decades that followed.

Elmer Benson was born in Appleton, Minnesota, in 1895, and raised on a strong brew of Midwestern populism. His father, Tom, was a member of the Non-Partisan League and an early supporter of the Farmer-Labor Party, which by the early 1920s had overtaken the Democrats in Minnesota. His mother was a granddaughter of a signer of the Norwegian Declaration of Independence and an even bigger free-thinker than her husband.

After studying law at the St. Paul College of Law and serving in the U.S. Army during World War I, Benson returned to Appleton. There, he combined a career in banking with an avocation for progressive politics. He built a strong Farmer-Labor organization in Swift County and throughout the Seventh Congressional District.

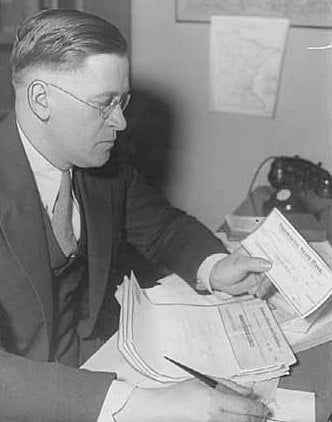

In 1932, the party’s popular governor, Floyd B. Olson, appointed Benson as Commissioner of Securities. On April 30 of the following year, Olson moved Benson to the crucial post of Commissioner of Banking. The reforms Benson implemented rescued hundreds of embattled small town bankers.

With his devotion to Farmer-Labor principles and his growing support in rural Minnesota, Benson quickly emerged as a favorite among Party activists. In 1935, Governor Olson appointed Benson to a vacancy in the U.S. Senate. When Olson died of stomach cancer the following year, FLP leaders chose Benson as the party’s candidate for governor.

As governor, Benson championed the most ambitious legislative agenda in Minnesota history. His platform combined support for the unemployed with New Deal-style social programs financed by increased taxes on big business and the wealthy.

Most of Benson’s proposals passed the Farmer-Labor-controlled House of Representatives. Only a few, however, survived the Republican-controlled Senate. One critic famously pointed out that although Floyd Olson had made radical statements in the past, “this SOB [Benson] actually means them!”

To an unprecedented degree, Benson used the power of his office to support the rights of labor. In the bitterly cold January of 1937, he ordered state officials to provide food and shelter to striking timber workers throughout northern Minnesota. That same year, he deployed the National Guard to protect the Newspaper Guild’s right to strike. He also refused to renew the notorious anti-labor Pinkerton Agency’s license in Minnesota. In perhaps the most dramatic intervention, Benson ordered Albert Lea’s anti-union sheriff to release striking workers from jail. He then personally took charge of talks between workers and a reluctant management.

Actions like these endeared Benson to many Farmer-Labor activists. They also created opposition. The governor’s support of the new Congress of Industrial Organizations angered leaders of the American Federation of Labor as the two groups competed for membership and power. The involvement of Communists in the CIO and the Benson administration more generally heightened this tension.

A bitter primary challenge from former Lieutenant Governor Hjalmer Petersen exposed these and other fissures within the FLP. In the 1938 general election, Benson was soundly defeated by Republican Harold Stassen. Stassen, a young reformer, promised a “middle path” between “rock-ribbed” Republican conservatism and alleged Farmer-Labor extremism.

From 1938 to 1944, Benson remained the FLP’s most prominent leader. However, the Party, though still out-pacing Minnesota’s Democrats, failed to compete successfully with the Republicans. In 1944, Benson reluctantly supported the merger of the Farmer-Labor and Democratic Parties, creating the Democratic Farmer-Labor Party (DFL).

In 1948, Benson broke with the Democrats to support the presidential campaign of Henry Wallace, a liberal opponent of the Cold War policies of Harry Truman. An epic struggle for the future direction of Minnesota progressivism ensued. Democrats, led by Hubert Humphrey and future DFL governor Orville Freeman, delivered a decisive defeat to Benson’s Farmer-Laborites.

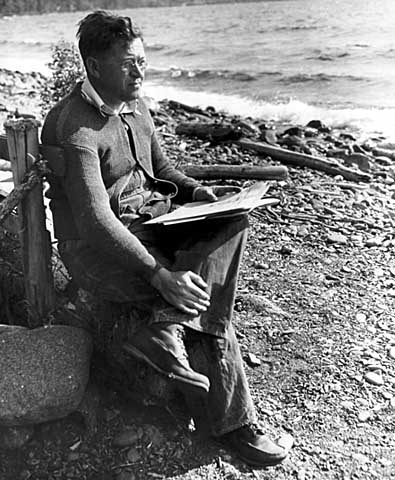

After Wallace’s landslide loss to Truman in 1948, Benson served as national chair of the Progressive Party, leading opposition to the emerging nuclear arms race and U.S. intervention in Korea. In August, 1951, suffering from encephalitis and under strict doctor’s orders, he retired to his home in Appleton. He remained out of the public eye until his death in 1985.