Topics

Category

Era

Immigration to the Iron Range, 1880–1930

During the early twentieth century, the population of the Iron Range was among the most ethnically diverse in Minnesota. Tens of thousands of immigrants arrived from Finland, Austria-Hungary, Italy, Sweden, Norway, Canada, England, and over thirty other places of origin. These immigrants mined the ore that made the Iron Range famous and built its communities.

Minnesota has three iron mining ranges, which are collectively known as the Iron Range. The Vermilion is the northernmost, and it began shipping ore in 1884. The Mesabi Range is the largest, and it started ore shipments in 1892. The Cuyuna Range first shipped ore in 1911 and is the southernmost range.

With the onset of mining operations, the population of the three ranges expanded rapidly. In 1885, there were fewer than five thousand people living on the Iron Range. By 1920, the population exceeded a hundred thousand. This growth was spurred by the need for labor in the mines and corresponded with a massive wave of immigration from southern and eastern Europe. Immigrants eventually constituted more than half of the Iron Range population. In the mines, they formed 85 percent of the workforce.

Forty-three different nationality groups populated the Iron Range. The earliest immigrants were Finnish, Swedish, Slovenian, Canadian, Norwegian, Cornish, and German. After 1900, the origins of the population expanded, with Italian, Croatian, Polish, Montenegrin, Serbian, Bulgarian, Romanian, Slovak, Hungarian, and Greek immigrants filling mining jobs. A sizeable Jewish population started main street businesses. Chinese immigrant men ran restaurants and laundries.

When the population began to stabilize after 1910, Finns made up the single largest immigrant nationality. They constituted a quarter of all foreign-born persons. Slovenes and Croats—referred to collectively as “Austrians”—were the next largest group at over 20 percent of the immigrant sector. Italians and Swedes each made up close to 10 percent of the foreign-born population.

For immigrants, life on the Iron Range was not easy. Mine laborers worked long hours and received low wages. Underground mines operated on a contract labor system—an arrangement in which miners received payment based on the amount of ore produced—which led to bribery. Miners paid to get assignments in the most accessible and therefore most profitable ore. Mining work was also dangerous. Hundreds of deaths occurred due to accidents, with the deadliest being the Milford Mine disaster in 1924.

Beyond the industrial workplace, immigrants faced other challenges. The cost of living was high. To maximize savings, immigrants lived in substandard housing conditions. In a practice known as the “hot bed system,” day- and night-shift workers alternated sleeping in the same beds. Unmarried immigrant women labored long, hard days as domestic servants. Married women rarely worked outside the home, but they supplemented family incomes by keeping boarders or lodgers.

In addition to material hardships, immigrants confronted social prejudices. Native-born Americans occupied the best-paying jobs at the mines. They viewed immigrants from northern European countries as “desirable” workers. For example, many Cornish immigrants entered supervisory roles. Southern and eastern European immigrants, however, occupied lower positions in the workforce hierarchy. Mining company officials described these immigrants as “black races” who were physically and intellectually inferior.

Community leaders likewise looked down on southern and eastern European immigrants. They objected to immigrants’ congested living situations, imbalanced sex ratios, perceived immorality, and association with political radicalism. The fact that many immigrants were Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, or Jewish caused further anxiety. Local chapters of the Ku Klux Klan developed during the 1920s in opposition to Catholic and Jewish immigrants.

Despite these challenges, immigrants adapted to the new circumstances. One key adaptation strategy was the formation of ethnic institutions. Saloons and socialist worker halls offered refuge from the hardships of mining. Fraternal and mutual benefit societies guaranteed financial support when accidents or deaths occurred. Churches and synagogues provided a spiritual home. Immigrants also constructed boarding houses, temperance societies, shops, consumer cooperatives, and newspapers.

Another adaptation strategy was the retention of connections with the homeland. Many immigrants came to the Iron Range only temporarily. Their aim was to save money and return to their countries of origin. During the early years of mining development, when most immigrants were men, this was especially common. But immigrants maintained homeland connections even when they moved permanently. They sent home money and exchanged letters with friends and family in the old country.

Ethnic institutions and homeland connections divided the immigrant population on the Iron Range. Each immigrant group had its own community life, and tensions existed between groups. In larger cities, for example, there were usually separate Catholic churches for the Irish, Slovenian and Croatian, and Italian populations. Immigrants continued to speak their native tongues. They resided in ethnic clusters. They married partners of the same nationality.

Over time, though, ethnic distinctions diminished. Shared experiences created a new, interethnic identity. One such experience—and a third strategy for adapting to life on the Iron Range—was workplace organization. The first large-scale strike occurred in 1907, when the Western Federation of Miners organized an ill-fated walk-out on the Mesabi. In 1916, the Industrial Workers of the World led the most important labor conflict in Iron Range history, but it failed as well.

Americanization efforts were more successful in breaking down ethnic distinctions. Following the 1916 strike, mining company officials sought to prevent further labor unrest by investing in corporate welfare programs. They supported community beautification projects, model villages, gardening contests, visiting nurses, picnics, and Christmas parties. The construction of modern parks and recreational facilities led to Iron Range communities fielding excellent athletic teams.

Public schools and libraries were especially important to Americanization efforts. Adults attended night schools to learn English and prepare for citizenship examinations. In an effort to target women, instruction even extended into immigrant neighborhoods. However, the greatest attention went to the children of immigrants. Iron Range school buildings were palaces of learning. When Hibbing built a $4 million high school in 1923, it was among the most impressive in the nation.

The era of mass immigration to the Iron Range ended at the close of the 1920s. In 1924, the U.S. Congress passed legislation that limited immigration from southern and eastern Europe. At the same time, iron mining operations became increasingly mechanized, reducing the size of the labor force. As second and later generations gradually outnumbered their immigrant forbearers, the Iron Range shifted from an “immigrant” population to an “ethnic” one.

Bibliography

Alanen, Arnold R. “Years of Change on the Iron Range.” In Minnesota in a Century of Change: The State and Its People Since 1900, edited by Clifford E. Clark, Jr., 155–194. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1989.

Berman, Hyman. “Education for Work and Labor Solidarity: The Immigrant Miners and Radicalism on the Mesabi Range.” Typescript, 1963. Immigration History Research Center.

Betten, Neil. “The Origins of Ethnic Radicalism in Northern Minnesota, 1900–1920.” International Migration Review 4, no. 2 (1970): 44–56.

Holmquist, June Drenning, ed. They Chose Minnesota: A Survey of the State’s Ethnic Groups. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1981.

Karni, Michael G., ed. Entrepreneurs and Immigrants: Life on the Industrial Frontier of Northeastern Minnesota. Chisholm, MN: Iron Range Research Center, 1991.

Lamppa, Marvin G. Minnesota’s Iron Country: Rich Ore, Rich Lives. Duluth: Lake Superior Port Cities, 2004.

Landis, Paul H. Three Iron Mining Towns: A Study in Cultural Change. Ann Arbor, MI: Edwards Brothers, 1938.

Moersch, Julius. “Iron Ore Mining in Minnesota.” Journal of Political Economy 10, no. 1 (1901): 94–103.

Pfeiffer, C. Whit. “From ‘Bohunks’ to Finns: The Scale of Life among the Ore Strippings of the Northwest.” The Survey, April 1, 1916.

Smith, Timothy L. “Educational Beginnings, 1884–1910.” Typescript, 1963. Immigration History Research Center.

——— . “Factors Affecting the Social Development of Iron Range Communities.” Typescript, 1963. Immigration History Research Center.

——— . “Religious Denominations as Ethnic Communities: A Regional Case Study.” Church History 35, no. 2 (1966): 207–226.

Syrjamaki, John. “Mesabi Communities: A Study of Their Development.” PhD diss., Yale University, 1940.

United States Immigration Commission. Reports of the Immigration Commission: Immigrants in Industries, Part 18: Iron Ore Mining. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1911.

Virtue, G.O. “The Minnesota Iron Ranges.” Bulletin of the Bureau of Labor, no. 84. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1909.

Related Resources

Primary

P1043

William J. Bell and family papers, 1886–1985

Manuscript Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

Description: Personal papers of a Presbyterian minister who worked with the immigrant population on the Iron Range.

Doe, R.K. “Where Melting Pot Melts: Remarkable Work Among Toilers of Mesaba Range—25,000 at Naturalization Night Schools.” New York Times, March 12, 1922.

Hodges, LeRoy. “Immigrant Life in the Ore Region of Northern Minnesota.” The Survey, September 7, 1912.

Edith Koivisto papers, 1904–1975

Manuscript Collection, Immigration History Research Center, Minneapolis

http://ihrc.umn.edu/research/vitrage/all/ko/ihrc1233.html

Description: Diaries and personal papers of a Finnish immigrant from Hibbing.

Mancina-Batinich, Mary Ellen. Italian Voices: Making Minnesota Our Home. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2007.

P753

Oliver Iron Mining Company records, 1901–1930

Manuscript Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

Description: Files and correspondence of the largest mining company on the Iron Range; includes information on immigrant workers, churches, and Americanization programs.

Pelto, Matti Hallila. Ready to Descend: A Minnesota Iron Ore Miner in the Underground, 1908–1913; The Journals of Matti Hallila Pelto. Translated by Vienna C. Saari Maki. New Brighton, MN: Sampo Publishing, 2000.

James S. Steel Oliver Iron Mining Company research files, 1860–1972

Manuscript Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/00181.xml

Description: Research materials compiled in 1963 for a history of the Oliver Iron Mining Company; includes information on ethnic groups and Americanization programs.

P728

James P. Vaughan papers, 1904–1963

Manuscript Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

Description: Files documenting the career of the superintendent of schools at Chisholm.

Walker, Irma W. “The Library an Americanizing Factor on the Range.” Wisconsin Library Bulletin 14, no. 8 (1918): 209–213.

Secondary

Alanen, Arnold R. “Early Labor Strife on Minnesota’s Mining Frontier, 1882–1906.” Minnesota History 52, no. 7 (1991): 246–263.

http://collections.mnhs.org/MNHistoryMagazine/articles/52/v52i07p246-263.pdf

Betten, Neil. “Strike on the Mesabi—1907.” Minnesota History 40, no. 7 (1967): 340–347.

http://collections.mnhs.org/MNHistoryMagazine/articles/40/v40i07p340-347.pdf

Blatnik, Frank Paul. “Culture Conflict: A Study of the Slovenes in Chisholm, Minnesota.” Master’s thesis, University of Minnesota, 1942.

Blee, Kathleen. “Family Ties and Class Conflict: The Politics of Immigrant Communities in the Great Lakes Region, 1890–1920.” Social Problems 31, no. 3 (1984): 311–321.

Chambers, Clarke A. “Welfare on Minnesota’s Iron Range.” Upper Midwest History 3 (1983): 1–40.

Eleff, Robert M. “The 1916 Minnesota Miners’ Strike Against U.S. Steel.” Minnesota History 51, no. 2 (1988): 63–74.

http://collections.mnhs.org/MNHistoryMagazine/articles/51/v51i02p063-074.pdf

Iron Range: A People’s History. Produced by Laurie Stern and Barbara Wiener. VHS. St. Paul: Twin Cities Public Television, 1994.

Jones, Barbara. “‘The Center of Culture and Helpfulness’: Buhl, Minnesota, Public Library’s Impact on the Early Twentieth-Century Iron Range.” Journal of the West 30, no. 3 (1991): 53–62.

Karni, Michael G. “Otto Walta: Finnish Folk Hero of the Iron Range.” Minnesota History 40, no. 8 (1967): 391–402.

http://collections.mnhs.org/MNHistoryMagazine/articles/40/v40i08p391-402.pdf

Kaups, Matti E. “The Finns in the Copper and Iron Ore Mines of the Western Great Lakes Region, 1864–1905: Some Preliminary Observations.” In The Finnish Experience in the Western Great Lakes Region: New Perspectives, edited by Michael G. Karni, Matti E. Kaups, and Douglas J. Ollila, Jr., 55–89. Vammala, Finland: Institute for Migration, 1975.

Nemanic, Mary Lou. One Day for Democracy: Independence Day and the Americanization of Iron Range Immigrants. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 2007.

Proshan, Chester Jay. “Eastern European Jewish Immigrants and Their Children on the Minnesota Iron Range, 1880s–1980s.” PhD diss., University of Minnesota, 1998.

Smith, Timothy L. “School and Community: The Quest of Equal Opportunity, 1910–1921.” Typescript, 1963. Immigration History Research Center.

Vecoli, Rudolph J. “Italians on Minnesota’s Iron Range.” In Italian Immigrants in Rural and Small Town America, edited by Rudolph J. Vecoli, 179–189. Staten Island, NY: American Italian Historical Association, 1987.

Web

Cuyuna Iron Range Heritage Network.

http://www.cuyunahistory.org

Hill Annex Mine State Park.

http://www.dnr.state.mn.us/state_parks/hill_annex_mine/index.html

Lake Vermilion-Soudan Underground Mine State Park.

http://www.dnr.state.mn.us/state_parks/lake_vermilion_soudan/index.html

Minnesota Discovery Center. The Museum of the Iron Range.

http://www.mndiscoverycenter.com/

Minnesota Humanities Center. Learn About the Iron Range.

http://humanitieslearning.org/resource/index.cfm?act=1&TagID=&CatID=0&SearchText=iron%20range&SortBy=1&mediatype=3&lurl=1

Related Images

Slovenian wedding in Eveleth

Slovene wedding, Eveleth, 1908.

Public domain

Holding Location

More Information

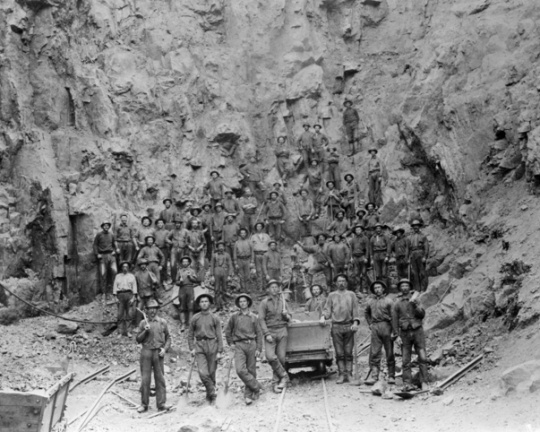

Tower-Soudan mine

Miners in the pit of the Tower-Soudan mine, 1890.

Public domain

Holding Location

More Information

Finnish Temperance Hall, Mt. Iron

Finnish Lutheran congregation in front of Finnish Temperance Hall, Mt. Iron, 1896.

Public domain

Holding Location

More Information

Boarding house residents near Troy Mine

Boarding house residents near Troy Mine, 1905.

Public domain

Holding Location

More Information

Construction of B'nai Abraham synagogue in Virginia

Construction of B'nai Abraham synagogue in Virginia, 1909.

Public domain

Holding Location

More Information

Suomalainen Raittiustalo, Virginia

Suomalainen Raittiustalo (Finnish temperance house), Virginia, 1910.

Public domain

Holding Location

More Information

Church in Ely

Church in Ely, 1913.

Public domain

Holding Location

More Information

Bohemian boy in Virginia

Bohemian boy, Virginia, 1914.

Public domain

Holding Location

More Information

Finnish Stock Company

Finnish Stock Company, Ely, 1915.

Public domain

Holding Location

More Information

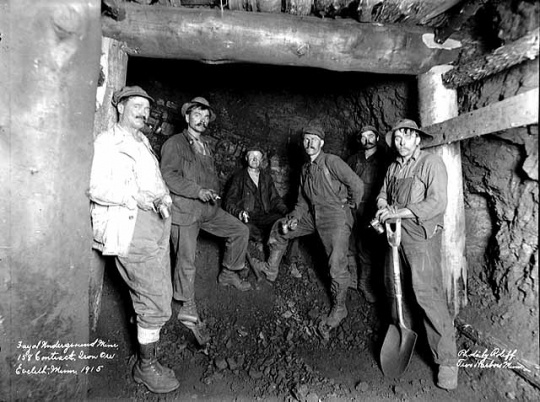

Fayal mine, Eveleth

Fayal underground mine, Eveleth, 1915.

Public domain

Holding Location

More Information

Italian American Hall, Eveleth

Italian American Hall, Eveleth, 1920.

Public domain

Holding Location

More Information

Ironton miners

Group of miners at Ironton, 1925.

Holding Location

More Information

Mary Harju Paavola

Finnish immigrant Mary Harju Paavola, 1925.

Holding Location

More Information

Mr. and Mrs. John Kleimola, Mt. Iron

Mr. and Mrs. John Kleimola, Mt. Iron, 1930.

Holding Location

More Information

Sons of Italy Fourth of July float

Sons of Italy Fourth of July float, Hibbing, 1930.

Holding Location

More Information

Related Articles

Turning Point

In 1892, iron ore shipments are sent for the first time from the Mesabi Range, which soon becomes the most important iron-mining region in the world.

Chronology

1884

1892

1898

1901

1901

1907

1911

1911

1916

1923

1924

1924

Bibliography

Alanen, Arnold R. “Years of Change on the Iron Range.” In Minnesota in a Century of Change: The State and Its People Since 1900, edited by Clifford E. Clark, Jr., 155–194. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1989.

Berman, Hyman. “Education for Work and Labor Solidarity: The Immigrant Miners and Radicalism on the Mesabi Range.” Typescript, 1963. Immigration History Research Center.

Betten, Neil. “The Origins of Ethnic Radicalism in Northern Minnesota, 1900–1920.” International Migration Review 4, no. 2 (1970): 44–56.

Holmquist, June Drenning, ed. They Chose Minnesota: A Survey of the State’s Ethnic Groups. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1981.

Karni, Michael G., ed. Entrepreneurs and Immigrants: Life on the Industrial Frontier of Northeastern Minnesota. Chisholm, MN: Iron Range Research Center, 1991.

Lamppa, Marvin G. Minnesota’s Iron Country: Rich Ore, Rich Lives. Duluth: Lake Superior Port Cities, 2004.

Landis, Paul H. Three Iron Mining Towns: A Study in Cultural Change. Ann Arbor, MI: Edwards Brothers, 1938.

Moersch, Julius. “Iron Ore Mining in Minnesota.” Journal of Political Economy 10, no. 1 (1901): 94–103.

Pfeiffer, C. Whit. “From ‘Bohunks’ to Finns: The Scale of Life among the Ore Strippings of the Northwest.” The Survey, April 1, 1916.

Smith, Timothy L. “Educational Beginnings, 1884–1910.” Typescript, 1963. Immigration History Research Center.

——— . “Factors Affecting the Social Development of Iron Range Communities.” Typescript, 1963. Immigration History Research Center.

——— . “Religious Denominations as Ethnic Communities: A Regional Case Study.” Church History 35, no. 2 (1966): 207–226.

Syrjamaki, John. “Mesabi Communities: A Study of Their Development.” PhD diss., Yale University, 1940.

United States Immigration Commission. Reports of the Immigration Commission: Immigrants in Industries, Part 18: Iron Ore Mining. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1911.

Virtue, G.O. “The Minnesota Iron Ranges.” Bulletin of the Bureau of Labor, no. 84. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1909.

Related Resources

Primary

P1043

William J. Bell and family papers, 1886–1985

Manuscript Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

Description: Personal papers of a Presbyterian minister who worked with the immigrant population on the Iron Range.

Doe, R.K. “Where Melting Pot Melts: Remarkable Work Among Toilers of Mesaba Range—25,000 at Naturalization Night Schools.” New York Times, March 12, 1922.

Hodges, LeRoy. “Immigrant Life in the Ore Region of Northern Minnesota.” The Survey, September 7, 1912.

Edith Koivisto papers, 1904–1975

Manuscript Collection, Immigration History Research Center, Minneapolis

http://ihrc.umn.edu/research/vitrage/all/ko/ihrc1233.html

Description: Diaries and personal papers of a Finnish immigrant from Hibbing.

Mancina-Batinich, Mary Ellen. Italian Voices: Making Minnesota Our Home. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2007.

P753

Oliver Iron Mining Company records, 1901–1930

Manuscript Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

Description: Files and correspondence of the largest mining company on the Iron Range; includes information on immigrant workers, churches, and Americanization programs.

Pelto, Matti Hallila. Ready to Descend: A Minnesota Iron Ore Miner in the Underground, 1908–1913; The Journals of Matti Hallila Pelto. Translated by Vienna C. Saari Maki. New Brighton, MN: Sampo Publishing, 2000.

James S. Steel Oliver Iron Mining Company research files, 1860–1972

Manuscript Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/00181.xml

Description: Research materials compiled in 1963 for a history of the Oliver Iron Mining Company; includes information on ethnic groups and Americanization programs.

P728

James P. Vaughan papers, 1904–1963

Manuscript Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

Description: Files documenting the career of the superintendent of schools at Chisholm.

Walker, Irma W. “The Library an Americanizing Factor on the Range.” Wisconsin Library Bulletin 14, no. 8 (1918): 209–213.

Secondary

Alanen, Arnold R. “Early Labor Strife on Minnesota’s Mining Frontier, 1882–1906.” Minnesota History 52, no. 7 (1991): 246–263.

http://collections.mnhs.org/MNHistoryMagazine/articles/52/v52i07p246-263.pdf

Betten, Neil. “Strike on the Mesabi—1907.” Minnesota History 40, no. 7 (1967): 340–347.

http://collections.mnhs.org/MNHistoryMagazine/articles/40/v40i07p340-347.pdf

Blatnik, Frank Paul. “Culture Conflict: A Study of the Slovenes in Chisholm, Minnesota.” Master’s thesis, University of Minnesota, 1942.

Blee, Kathleen. “Family Ties and Class Conflict: The Politics of Immigrant Communities in the Great Lakes Region, 1890–1920.” Social Problems 31, no. 3 (1984): 311–321.

Chambers, Clarke A. “Welfare on Minnesota’s Iron Range.” Upper Midwest History 3 (1983): 1–40.

Eleff, Robert M. “The 1916 Minnesota Miners’ Strike Against U.S. Steel.” Minnesota History 51, no. 2 (1988): 63–74.

http://collections.mnhs.org/MNHistoryMagazine/articles/51/v51i02p063-074.pdf

Iron Range: A People’s History. Produced by Laurie Stern and Barbara Wiener. VHS. St. Paul: Twin Cities Public Television, 1994.

Jones, Barbara. “‘The Center of Culture and Helpfulness’: Buhl, Minnesota, Public Library’s Impact on the Early Twentieth-Century Iron Range.” Journal of the West 30, no. 3 (1991): 53–62.

Karni, Michael G. “Otto Walta: Finnish Folk Hero of the Iron Range.” Minnesota History 40, no. 8 (1967): 391–402.

http://collections.mnhs.org/MNHistoryMagazine/articles/40/v40i08p391-402.pdf

Kaups, Matti E. “The Finns in the Copper and Iron Ore Mines of the Western Great Lakes Region, 1864–1905: Some Preliminary Observations.” In The Finnish Experience in the Western Great Lakes Region: New Perspectives, edited by Michael G. Karni, Matti E. Kaups, and Douglas J. Ollila, Jr., 55–89. Vammala, Finland: Institute for Migration, 1975.

Nemanic, Mary Lou. One Day for Democracy: Independence Day and the Americanization of Iron Range Immigrants. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 2007.

Proshan, Chester Jay. “Eastern European Jewish Immigrants and Their Children on the Minnesota Iron Range, 1880s–1980s.” PhD diss., University of Minnesota, 1998.

Smith, Timothy L. “School and Community: The Quest of Equal Opportunity, 1910–1921.” Typescript, 1963. Immigration History Research Center.

Vecoli, Rudolph J. “Italians on Minnesota’s Iron Range.” In Italian Immigrants in Rural and Small Town America, edited by Rudolph J. Vecoli, 179–189. Staten Island, NY: American Italian Historical Association, 1987.

Web

Cuyuna Iron Range Heritage Network.

http://www.cuyunahistory.org

Hill Annex Mine State Park.

http://www.dnr.state.mn.us/state_parks/hill_annex_mine/index.html

Lake Vermilion-Soudan Underground Mine State Park.

http://www.dnr.state.mn.us/state_parks/lake_vermilion_soudan/index.html

Minnesota Discovery Center. The Museum of the Iron Range.

http://www.mndiscoverycenter.com/

Minnesota Humanities Center. Learn About the Iron Range.

http://humanitieslearning.org/resource/index.cfm?act=1&TagID=&CatID=0&SearchText=iron%20range&SortBy=1&mediatype=3&lurl=1