Topics

Category

Era

American Indian Movement (AIM)

Flag of the American Indian Movement (AIM). Image by Wikimedia Commons user Tripodero, January 6, 2018.

The American Indian Movement (AIM), founded by grassroots activists in Minneapolis in 1968, first sought to improve conditions for Native Americans who had recently moved to cities. It grew into an international movement whose goals included the full restoration of tribal sovereignty and treaty rights. Through a long campaign of “confrontation politics,” AIM is often credited with restoring hope to Native peoples.

AIM’s rise occurred during a time of extreme hardship for Native Americans in the Twin Cities. A decade earlier, the federal government had passed the Indian Relocation Act, which promised good jobs and housing for Natives who moved from reservations into cities. Many of the thousands who migrated, however, found only low-wage labor, substandard housing, discrimination, violence, and despair. Their spiritual ceremonies, outlawed since 1884, were still illegal.

AIM’s initial actions were meant to bolster Minneapolis’s Native population. To aid victims of police abuse, they formed the AIM Patrol. AIM also helped establish the Legal Rights Center, which provided free representation to the poor, and the Indian Health Board, which provided Native-centric medical care. In 1972, AIM founded the Heart of the Earth Survival School.

Later that year, AIM widened its focus to the national stage, joining the Trail of Broken Treaties. The purpose of the walk—which began on the West Coast and ended in Washington, DC—was to demand that the government fulfill its treaty commitments. Upon arrival, AIM members occupied the Bureau of Indian Affairs Building. After nearly a week, the Nixon administration agreed to consider their demands and pay for them to return home. The action made AIM a target of COINTELPRO, the FBI’s covert operation meant to disrupt domestic political organizations.

In 1973, AIM received a request from Gladys Bissonette of the Oglala Sioux Civil Rights Organization. The traditional Lakota people on the Pine Ridge Reservation were being terrorized by white vigilantes and supporters of tribal president Dick Wilson. In response, AIM joined the traditional Lakotas in occupying the village of Wounded Knee. Surrounded by hundreds of federal agents with military weaponry, the Natives battled government forces for seventy-one days. They demanded hearings on their treaty and investigation of the BIA. Two Native people, Buddy Lamont and Frank Clearwater, were killed. Major news organizations remained onsite throughout the conflict, reporting headlines across the world.

While three men—Dennis Banks, Clyde Bellecourt, and Russell Means—are generally acknowledged as leaders of AIM, many Native women also made extraordinary, often anonymous, sacrifices for the movement. Among these were Pat Bellanger, an original AIM member whose nearly fifty years of service to the movement earned her the nickname “Grandma AIM”; Sarah Bad Heart Bull, who was beaten and jailed in Custer, South Dakota, while protesting her son’s murder; and Anna Mae Aquash (Mi’kmaq First Nation), who took up arms and fought alongside the men at Wounded Knee.

History may view AIM as a militant group, but AIM saw itself as a spiritual movement. Before, during, and after Wounded Knee, AIM members participated in Sun Dances, sweat lodges, and other long-hidden ceremonies, helping to coax them from the shadows.

In 1974, Banks and Means were tried for conspiracy and assault at the federal courthouse in St. Paul. After a nine-month trial, AIM declared victory when Judge Fred J. Nichols, citing government misconduct, dismissed all charges. The movement, however, had begun to splinter. Infighting, jealousy, and the FBI’s efforts to divide them had sewn suspicion and paranoia. The murder of Anna Mae Aquash, whose body was discovered on Pine Ridge on February 24, 1975, marked the beginning of the end of a united AIM. Members blamed the FBI and one another, destroying trust within the movement.

AIM’s last major action took place in 1978. The Longest Walk was commenced to protest the imprisonment of AIM activist Leonard Peltier and eleven federal bills that threatened treaty rights. Several hundred Natives marched from San Francisco to Washington, DC. The walk achieved much of its purpose: the anti-Native bills were defeated. But the greatest victory of the walk, and perhaps the movement, came on August 11, just days after protestors arrived: President Jimmy Carter signed the American Indian Religious Freedom Act, lifting the ban on Native American spiritual practices.

Bellecourt continued to lead the Minneapolis branch of AIM into the 2010s, fighting derogatory team names and police misconduct and founding the AIM Interpretive Center. He died in 2022.

Bibliography

Banks, Dennis. Ojibwe Warrior. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2011.

Bellecourt, Clyde, as told to Jon Lurie. The Thunder Before the Storm: The Autobiography of Clyde Bellecourt. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2017.

Davis, Julie L. Survival Schools: The American Indian Movement and Community Education in the Twin Cities. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013.

Furst, Randy. “Pat Bellanger, Prominent Indian Activist from Minneapolis, Dies.” Minneapolis Star-Tribune, April 30, 2015.

Konigsberg, Eric. “Who Killed Anna Mae?” New York Times, April 25, 2014.

Lichtenstein, Grace. “16 Sioux Sought by F.B.I. In Slaying of 2 Agents.” New York Times, June 28, 1975.

Makin, Kirk. “Retraction Ends 25 Years of Guilt.” Globe and Mail, November 11, 2000.

Matthiessen, Peter. In the Spirit of Crazy Horse. New York: Viking Penguin, 1983.

McFadden, Robert D. “Dennis Banks, American Indian Civil Rights Leader, Dies at 80.” New York Times, October 30, 2017.

Ray, Charles Michael. “Pine Ridge Reservation Deaths to be Reinvestigated.” NPR’s Weekend Edition, August 18, 2012.

Smith, Paul Chaat, and Robert Allen Warrior. Like a Hurricane: The Indian Movement from Alcatraz to Wounded Knee. New York: New Press, 1996.

Waterman Wittstock, Laura, and Dick Bancroft. We Are Still Here: A Photographic History of the American Indian Movement. St. Paul: Borealis Books, 2013.

Related Resources

Primary

Red School House records, 1986–

Manuscripts Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

Description: School board minutes, personal correspondence, notes on lawsuits, newspaper articles, school handbooks, financial reports, tax reports, and other files accumulated by Peter Dodge during his years as director of a Native American Survival School in St. Paul, an alternative pre K-12 school established in 1972 that integrated Native culture and history with modern day concepts for survival

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/00878.xml

Wounded Knee Legal Defense/Offense Committee records, 1966–1990

Manuscripts Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

Description: Records documenting the history, internal operation, and legal practice of a committee established by lawyers, legal workers, and others dedicated to the defense of activists involved in the American Indian Movement of the 1970s.

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/00229.xml

Secondary

Dunbar-Ortiz, Roxanne. An Indigenous People’s History of the United States. Boston: Beacon Press, 2014.

Means, Russell, and Marvin J. Wolf. Where White Men Fear to Tread. New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 1995.

Peltier, Leonard, and Harvey Arden. Prison Writings: My Life Is My Sundance. St. Martin’s Griffin, 2000.

Redford, Robert, and Michael Apted. “Incident at Oglala: The Leonard Peltier Story.” DVD. Lions Gate, 2004.

Salt, Lynn, and David Mueller. “A Good Day to Die: Dennis Banks and the American Indian Movement.” DVD. Journeyman Pictures, 2010.

Sayer, John William. Ghost Dancing the Law: The Wounded Knee Trials. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000.

Web

Benton-Banai, Eddie (Bawdwaywidun). Oral history interview with Lorraine Norgard in Hayward, Wisconsin, March 5, 1999. Waasa Inaabidaa Archives, Norrgard Anishinaabe Collection, University of Minnesota Duluth.

https://collection.mndigital.org/catalog/umd:3907#/kaltura_video

Related Video

Storied 1968: American Indian Movement

AIM—the American Indian Movement—began in Minneapolis, Minnesota, on July 28, 1968. It took form when 200 Native people turned out for a meeting called by a group of community activists led by George Mitchell, Dennis Banks, and Clyde Bellecourt. In this video, Bellecourt talks about about the movement and its growth over the past fifty years.

Much of the still photography in this piece was taken by Dick Bancroft, author of We Are Still Here: A Photographic History of the American Indian Movement (Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2013). The remaining images are courtesy of the American Indian Movement Interpretive Center.

More Information

Articles

Related Audio

Excerpt of AIM song

American Indian Movement (AIM) members singing the AIM song, mid-1970s. From What Now, People? Vol. 2, Paredon Records, 1977.

More Information

Articles

Related Images

American Indian Movement flag

Flag of the American Indian Movement (AIM). Image by Wikimedia Commons user Tripodero, January 6, 2018.

Public domain

Holding Location

Articles

First AIM board members, 1968

The first board members of the American Indian Movement (AIM), 1968. Photograph by Roger Woo, courtesy of the American Indian Movement Interpretative Center.

All rights reserved

Holding Location

AIM-organized Forum on Police Brutality

A woman at a podium speaks into a microphone as audience members look on, ca. 1968. Photograph by Roger Woo, courtesy of the American Indian Movement Interpretative Center.

All rights reserved

Holding Location

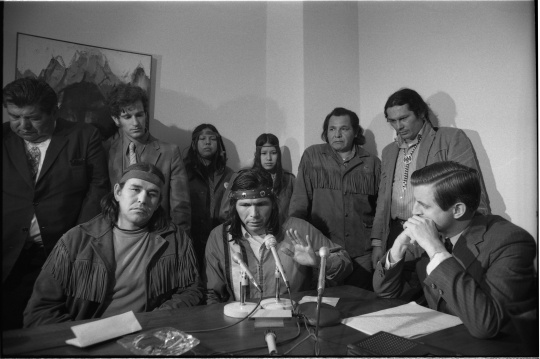

AIM news conference, 1971

After the occupation of Wounded Knee, South Dakota, Dennis Banks (at microphone) and other AIM leaders hold a news conference with US Senator Walter Mondale (right) on May 21, 1971. From the Minneapolis and St Paul newspaper negatives collection, Minnesota Historical Society.

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

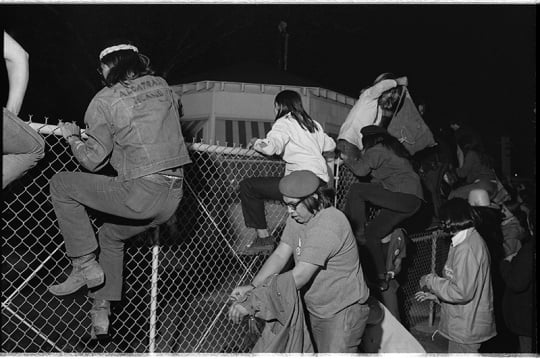

AIM at Twin Cities Naval Air Station

On May 17, 1971, AIM activists scaled a fence to begin their occupation of the Twin Cities Naval Air Station. From the Minneapolis and St Paul newspaper negatives collection, Minnesota Historical Society.

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

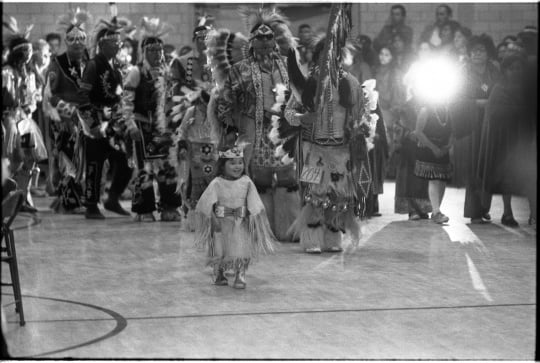

Dancers at AIM powwow, 1972

Dancers gather during a powwow at an American Indian Movement (AIM) convention held in Cass Lake on May 14, 1972. From the Minneapolis and St Paul newspaper negatives collection, Minnesota Historical Society.

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

Sarah Bad Heart Bull and AIM members in Custer, South Dakota

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

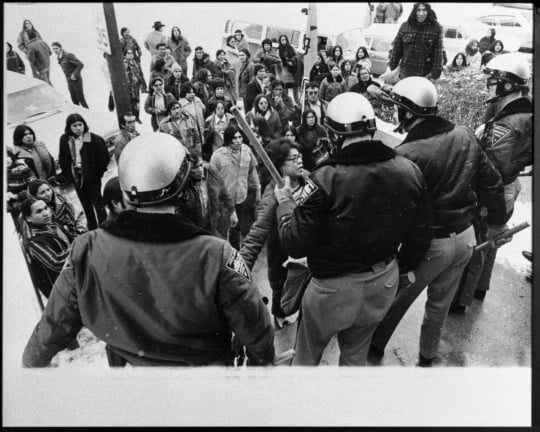

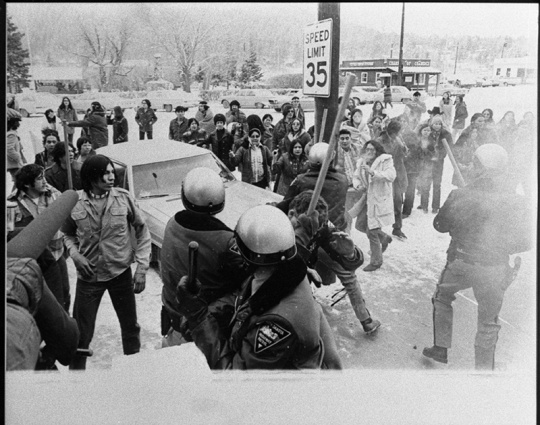

AIM protest in Custer, South Dakota

American Indian Movement (AIM) activists confront law enforcement officers in Custer, South Dakota, February 6, 1973. From box 3 (152.B.11.3B) of Wounded Knee Legal Defense / Offense Committee records, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul.

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

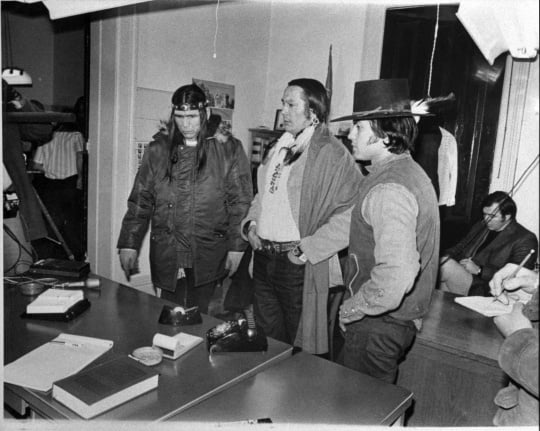

Dennis Banks and Russell Means in Custer, South Dakota, 1973

Dennis Banks (left), Russell Means (center), and David Hill (right) inside the courthouse in Custer, South Dakota, 1973. From box 3 (152.B.11.3B) of Wounded Knee Legal Defense / Offense Committee records, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul.

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

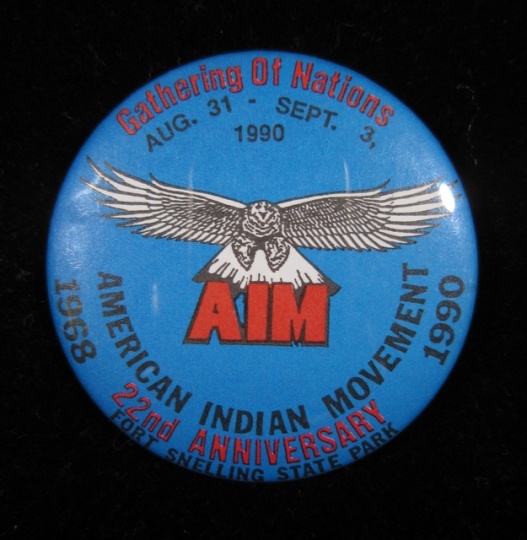

American Indian Movement (AIM) button

American Indian Movement (AIM) button from the AIM powwow at the Minneapolis American Indian Center, December 29, 1990.

All rights reserved

Articles

More Information

Tipi and AIM sign on the grounds of the Washington Monument

Tipi with American Indian Movement (AIM) sign on the grounds of the Washington Monument, Washington, DC, during the "Longest Walk" (1978). Original in the US New & World Report collection in the Library of Congress’s prints and photographs division.

Public domain

Holding Location

Articles

American Indian Movement (AIM) button

American Indian Movement (AIM) button from the AIM powwow held at the Minneapolis American Indian Center, December 29, 1990.

All rights reserved

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

Clyde Bellecourt and Dennis Banks

Clyde Bellecourt (left) and Dennis Banks (right) field calls from reporters at Pine Ridge Tribal Headquarters. Photograph by Jon Lurie, 1998. Used with the permission of Jon Lurie.

All rights reserved

Articles

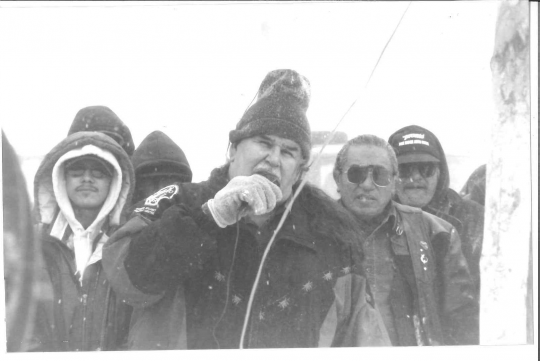

Clyde Bellecourt and others at Wounded Knee

Clyde Bellecourt addresses the twenty-five-year commemoration of the AIM occupation of Wounded Knee, South Dakota. Photograph by Jon Lurie, 1998. Used with the permission of Jon Lurie.

All rights reserved

Articles

Camp at Wounded Knee

The American Indian Movement flag flies over a camp of tipis at Wounded Knee, South Dakota. Photograph by Jon Lurie, 1998. Used with the permission of Jon Lurie.

All rights reserved

Articles

Upside-down American flag flying at Wounded Knee

An American Indian Movement (AIM) flag flies at Wounded Knee, South Dakota, 1998. AIM members adopted the upside-down US flag, a signal of distress, as a symbol of their movement. Photograph by Jon Lurie, 1998. Used with the permission of Jon Lurie.

All rights reserved

Articles

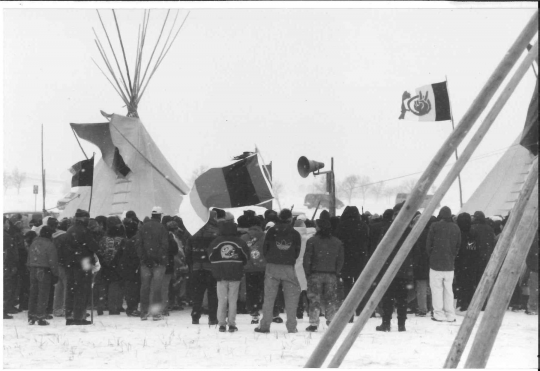

AIM members observing the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Wounded Knee occupation

AIM members gather at Wounded Knee to commemorate the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Wounded Knee occupation (1973) in South Dakota. Photograph by Jon Lurie, 1998. Used with the permission of Jon Lurie.

Articles

Gun salute during the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Wounded Knee occupation

American Indian Movement (AIM) members honor those who died in the Wounded Knee occupation with a gun salute. Photograph by Jon Lurie, 1998. Used with the permission of Jon Lurie.

All rights reserved

Articles

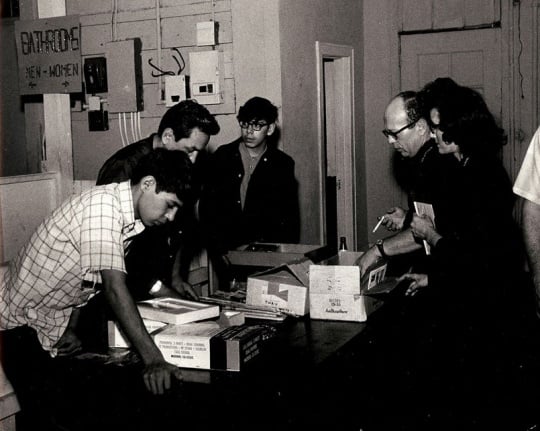

AIM Patrol receiving donations

Five people look over cardboard boxes filled with supplies, September 14, 1968. Photograph by Roger Woo, courtesy of the American Indian Interpretative Center.

All rights reserved

Holding Location

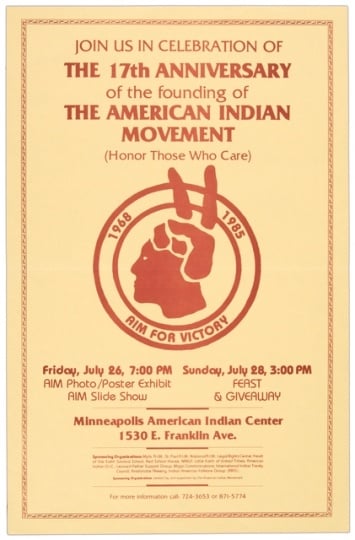

American Indian Movement flyer

Flyer advertising an event held to celebrate the seventeenth anniversary of the founding of the American Indian Movement (AIM), 1985.

Holding Location

More Information

American Indian Movement (AIM) patch

American Indian Movement (AIM) patch commemorating the eighty-third anniversary of the Wounded Knee massacre in South Dakota, 1973.

All rights reserved

Holding Location

More Information

Related Articles

Turning Point

In 1968, AIM is founded at a Minneapolis meeting of Concerned Indian Americans (CIA). The name “American Indian Movement” is adopted at the suggestion of Alberta Downwind, who opposes sharing the acronym “CIA” with a US intelligence agency. Dennis Banks and Clyde Bellecourt are nominated as leaders.

Chronology

1962

1968

1970

1971

1972

1973

1973

1974

1975

1976

1977

1978

1978

Bibliography

Banks, Dennis. Ojibwe Warrior. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2011.

Bellecourt, Clyde, as told to Jon Lurie. The Thunder Before the Storm: The Autobiography of Clyde Bellecourt. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2017.

Davis, Julie L. Survival Schools: The American Indian Movement and Community Education in the Twin Cities. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013.

Furst, Randy. “Pat Bellanger, Prominent Indian Activist from Minneapolis, Dies.” Minneapolis Star-Tribune, April 30, 2015.

Konigsberg, Eric. “Who Killed Anna Mae?” New York Times, April 25, 2014.

Lichtenstein, Grace. “16 Sioux Sought by F.B.I. In Slaying of 2 Agents.” New York Times, June 28, 1975.

Makin, Kirk. “Retraction Ends 25 Years of Guilt.” Globe and Mail, November 11, 2000.

Matthiessen, Peter. In the Spirit of Crazy Horse. New York: Viking Penguin, 1983.

McFadden, Robert D. “Dennis Banks, American Indian Civil Rights Leader, Dies at 80.” New York Times, October 30, 2017.

Ray, Charles Michael. “Pine Ridge Reservation Deaths to be Reinvestigated.” NPR’s Weekend Edition, August 18, 2012.

Smith, Paul Chaat, and Robert Allen Warrior. Like a Hurricane: The Indian Movement from Alcatraz to Wounded Knee. New York: New Press, 1996.

Waterman Wittstock, Laura, and Dick Bancroft. We Are Still Here: A Photographic History of the American Indian Movement. St. Paul: Borealis Books, 2013.

Related Resources

Primary

Red School House records, 1986–

Manuscripts Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

Description: School board minutes, personal correspondence, notes on lawsuits, newspaper articles, school handbooks, financial reports, tax reports, and other files accumulated by Peter Dodge during his years as director of a Native American Survival School in St. Paul, an alternative pre K-12 school established in 1972 that integrated Native culture and history with modern day concepts for survival

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/00878.xml

Wounded Knee Legal Defense/Offense Committee records, 1966–1990

Manuscripts Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

Description: Records documenting the history, internal operation, and legal practice of a committee established by lawyers, legal workers, and others dedicated to the defense of activists involved in the American Indian Movement of the 1970s.

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/00229.xml

Secondary

Dunbar-Ortiz, Roxanne. An Indigenous People’s History of the United States. Boston: Beacon Press, 2014.

Means, Russell, and Marvin J. Wolf. Where White Men Fear to Tread. New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 1995.

Peltier, Leonard, and Harvey Arden. Prison Writings: My Life Is My Sundance. St. Martin’s Griffin, 2000.

Redford, Robert, and Michael Apted. “Incident at Oglala: The Leonard Peltier Story.” DVD. Lions Gate, 2004.

Salt, Lynn, and David Mueller. “A Good Day to Die: Dennis Banks and the American Indian Movement.” DVD. Journeyman Pictures, 2010.

Sayer, John William. Ghost Dancing the Law: The Wounded Knee Trials. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000.

Web

Benton-Banai, Eddie (Bawdwaywidun). Oral history interview with Lorraine Norgard in Hayward, Wisconsin, March 5, 1999. Waasa Inaabidaa Archives, Norrgard Anishinaabe Collection, University of Minnesota Duluth.

https://collection.mndigital.org/catalog/umd:3907#/kaltura_video