From November 1944 to late October 1945, Dr. Ancel Keys paid close attention to hunger. He supervised thirty-six young male volunteers in a "starvation experiment," funded by the U.S. Army. This landmark effort at the University of Minnesota led to broad new understandings of nutrition and health.

Keys was a physiologist, interested in how food and human behavior related to one another. He had already studied the effects of high altitudes on heart health. In 1941 he created the famous "K rations," nutritional packets supplied to servicemen fighting in World War II. This new study was not really about starving. It was researching how to "re-feed" the millions of war victims, prisoners, and refugees all over the world.

The government was concerned that starvation during the war could lead to enormous relief challenges when it ended. If America led the effort to feed the world's hunger, it would gain global political advantages as well. So Keys, his staff, and his subjects were hoping to find the most efficient way to turn famine around.

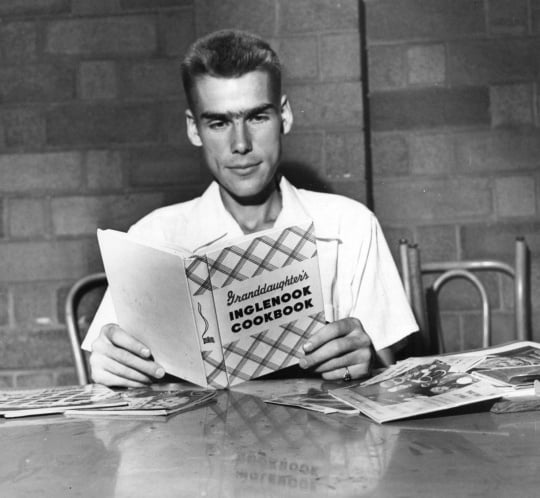

The experiment subjects were men of mostly college age. They were conscientious objectors, pacifists exempted from fighting. They had been working in unpaid, uninspiring alternate service tasks, yet they were idealists about world peace. Participating in a study that could lead to international understanding was appealing.

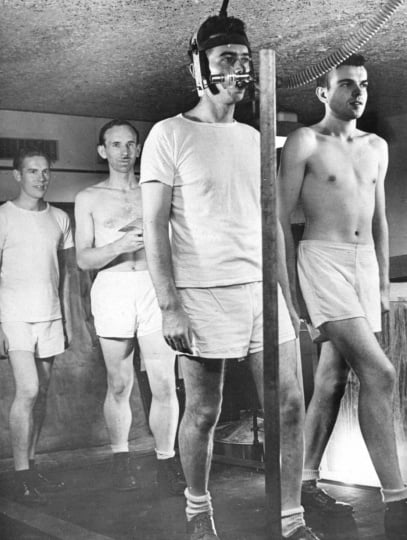

Keys's study was divided into three periods: first, three months of "control feeding," with normal diets and exercise, to establish a base of health and fitness. Then came six months of starvation, on a bland diet that imitated what was available to war victims - macaroni, turnips, weak soup, potatoes, rutabaga. Finally, the third stage was three months of re-feeding with a gradual increase of calories and amounts of food. There was more variety in the menu as well.

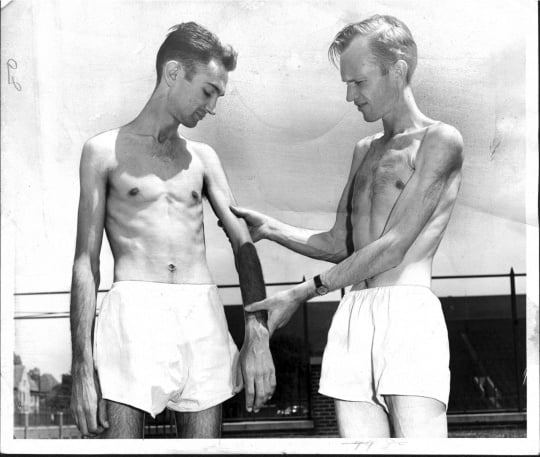

Each stage of the study also examined psychological and physical health. The men were required to walk twenty-two miles a week, and were often tested on strenuous treadmill exercises. Not surprisingly, as the months went by the men's weight dropped (most lost twenty four percent of their original weight), and their emotional health suffered. Keys's staff psychologist, Josef Brozek, monitored their minds just as closely as their bodies.

Keys's study was not the only one performed on conscientious objectors. Other, even riskier studies used similar volunteers to research malaria, typhus and pneumonia. "Guinea pigs" was used for the first time to describe humans undergoing such trials.

Simultaneously, doctors in both Nazi Germany and Japan were subjecting non-volunteer subjects to cruel experiments of questionable medical value. The world only became fully aware of these efforts after the war. In every case, whether in the U.S. or other nations, the tests raised enormous ethical dilemmas. Ancel Keys was aware of this, and wrestled with his strategy, sometimes in discussion with the subjects themselves.

Although two of the thirty six original volunteers were dismissed for cheating, and two more had to drop out for health reasons, the remaining thirty two men proved remarkably resilient. Keys had hoped to find some possible ideal mix of vitamins and/or protein for "relief feeding" efforts, but ultimately the increase in calories eaten was the real solution. By the study's end, the subjects' health and moods had improved greatly. In the years that followed they went on to respected, even distinguished careers. One volunteer, Max Kampelman, became a diplomat, negotiating arms control reductions for both the Carter and Reagan administrations.

The full, two-volume report of Ancel Keys's study, titled The Biology of Human Starvation, wasn't published until 1950. It remains a primary reference in the study of hunger. However, enough was known by the end of the war about "relief feeding" that aid programs worldwide knew the value of restoring emotional health and stability, as well as calorie intake, in starving people. So the experiment had both immediate and long-lasting impact.