Topics

Category

Era

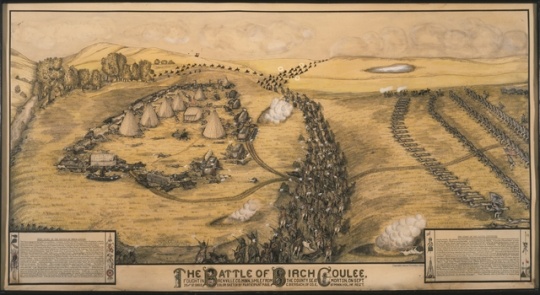

Battle of Birch Coulee, September 2–3, 1862

The Battle of Birch Coulee, fought between September 2 and 3, 1862, was the worst defeat the United States suffered and the Dakotas' most successful engagement during the US–Dakota War of 1862. Over thirty hours, approximately 200 Dakota warriors pinned down a Union force of 170 newly recruited US volunteers, militia, and civilians from the area, who were unable to move until Henry Sibley's main army arrived.

The US–Dakota War of 1862, a formative event in the history of Minnesota, was initiated by factions of the Dakota who had endured years of repeatedly broken promises by the federal government and were starving as they waited for annuity payments owed to them. The Battle at Birch Coulee was the longest battle of the war.

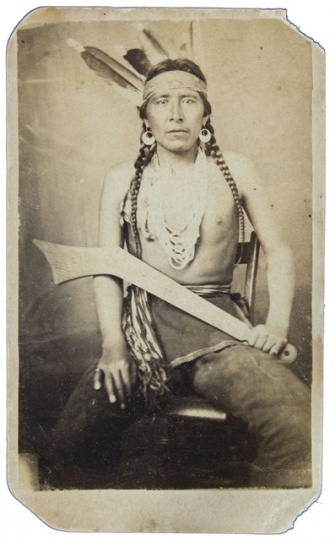

After initial battles with Union soldiers and attacks on civilian settlers, Dakota fighters, under the command of Ta Oyate Duta (His Red Nation, also known as Little Crow), split off into two groups. The first, commanded by Ta Oyate Duta, went east. The other group, under Zitka Ta Hota (Gray Bird), moved toward New Ulm, with the goal of taking the city. With him were the leaders Hu Shasha (Red Legs), Wambdi Tanka (Big Eagle), and Maka To (Blue Earth). On their way there, they encountered a camp of US soldiers in a tactically weak position at Birch Coulee. Putting aside their aims for New Ulm, the two hundred Dakota fighters decided to attack at dawn on September 2.

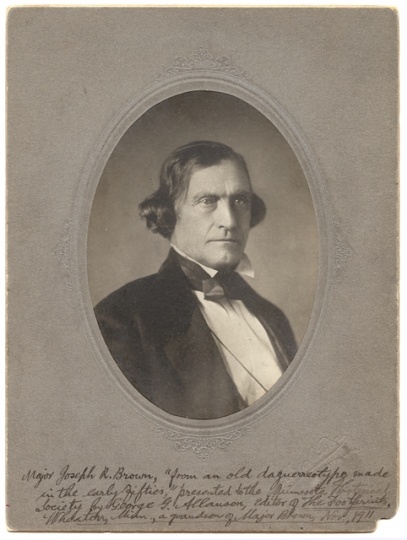

Two days earlier, on August 31, approximately 150 men under the command of Major Joseph Brown left Fort Ridgely to bury dead bodies from earlier attacks and seek out survivors. Brown had been a successful trader, but he was not an experienced military commander. After a day on burial detail, the force camped for the night on the prairie. The next day, the party continued their grisly task and discovered Justine Kreigher, a woman who had been wounded in earlier fighting. That night, Hiram Grant selected a camping site near water at Birch Coulee while Brown was away searching for signs of Dakota in the area. While soldiers under his command felt their position vulnerable, Grant was confident that there were no Dakota around.

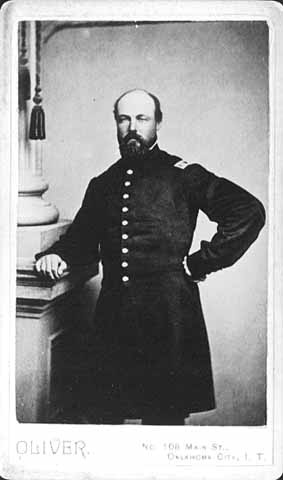

The site would prove to be tactically unsound for the Union forces. The campsite was a short but significant distance from fresh water, and it was near trees and high grass that would provide cover for Dakota warriors. Grant also placed guard posts too close to camp for a warning to do any good. When morning arrived, the Dakota took advantage of the Union camp's weaknesses and attacked. Though spotted by a guard, they were able to severely damage the federal force within the first few minutes of the fighting. Most US casualties occurred during this critical time. The Dakota poured gunfire into the camp and killed nearly all of the horses there. Though he ultimately survived the battle, Brown was shot in the neck during these opening moments, and Joseph Anderson took charge of the defense. US soldiers dug rifle pits and used horse carcasses to shield themselves from the bullets.

Somewhat surprised by a Union force larger than they expected, the Dakota decided to wait while the sun and lack of water did their work on the besieged troops, rather than risk their own warriors on a frontal assault. The US soldiers spent the day pinned down by desultory fire and baking under the hot sun.

Hearing what his scouts thought might be the sound of gunfire, Colonel Henry Sibley sent Colonel Samuel McPhail with 240 men from Fort Ridgely to see what was happening. McPhail arrived at the siege hours into the battle, but was fooled by a ruse. Chief Mankato and a small force of Dakota warriors convinced McPhail that he faced several hundred Dakota fighters. Rather than engage the fight, McPhail chose to camp two miles away and send for help from the fort.

The next day, Sibley himself brought relief for the besieged men. When he approached with a large force, the Dakota fighters retreated. The US casualties in the battle were thirteen dead, almost fifty wounded, and ninety horses killed. Wamdi Tanka's account only mentions two deaths among their warriors.

Bibliography

Anderson, Clayton, and Alan R. Woolworth, eds. Through Dakota Eyes: Narrative Accounts of the Minnesota Indian War of 1862. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1988.

Carley, Kenneth. The Dakota War of 1862. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2001.

Christgau, John. Birch Coulie: The Epic Battle of the Dakota War. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2012.

Folwell, William Watts. A History of Minnesota. Vol. II. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1961.

Related Resources

Primary

Anderson, Joseph, "Battle of Birch Coolie." Saint Paul Weekly Pioneer and Democrat, September 12, 1862.

"The Indian War." Saint Paul Weekly Pioneer and Democrat, September 12, 1862.

Barnes, T.C. Recollections of an Eventful Life. Typescript, 1917.

Boyd, Robert K. The Battle of Birch Coulee: A Wounded Man's Description of a Battle with the Indians. Eau Claire: Herges Printing Company, 1925.

———. Two Indian Battles: Battle of the Little Big Horn, June 25, 1876; Battle of Birch Coulee, Sept. 2 and 3rd, 1862. Eau Claire, 1928.

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/lb00030/lb00030-000001.pdf

———. "How the Indians Fought: A New Era in Skirmish Fighting, by a Survivor of the Battle of Birch Cooley." Minnesota History 11, no. 3 (September 1930): 299–304.

http://collections.mnhs.org/MNHistoryMagazine/articles/11/v11i03p299-304.pdf

———. "The Birch Cooley Monument." Minnesota History 12, no. 3 (September 1931): 297–301.

http://collections.mnhs.org/MNHistoryMagazine/articles/12/v12i03p297-301.pdf

Connolly, A.P. Minneapolis and the GAR: With a Vivid Account of the Battle of Birch Coulee, Sept. 2 and 3, the Battle of Wood Lake, Sept 23, the Release of the Women and Children Captives at Camp Release, Sept. 26, 1862. Minneapolis: A.P. Connolly, 1906.

Egan, James Joseph. The Battle of Birch Cooley. Renville County: Renville County Birch Cooley Memorial Association, 1927.

Holcombe, Return I., "A Sioux Story of the War: Chief Big Eagle's Account of its Important Incidents." St. Paul Pioneer Press, July 1, 1894.

http://www.startribune.com/july-1-1894-chief-big-eagle-speaks/166360646/

Sibley, Henry H. A Report to the Adjutant General on the Battle of Birch Coulee, September 4, 1862.

P694

Oversized C26

Robert Knowles Boyd Papers, 1925–1930

Manuscript Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

Description: Manuscripts by Boyd about the US-Dakota War. Also included is an oversized map of the Battle of Birch Coulee.

P841

Return I. Holcombe Papers, 1859–1916

Manuscript Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/00711.xml

Description: The papers of St. Paul journalist and historian, Return Holcombe, includes reminisces from Joseph R. Brown and Dr. Jared W. Daniels, and others.

M87

James T. Ramer Diary and Letter, 1862, 1865

Manuscript Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

Description: Diary kept by James T. Ramer, a Minnesota soldier, before and after the Battle of Birch Coulee.

Letter from Lieutenant Thomas van Etten, October 10, 1862

Manuscript Collection, Nicollet County Historical Society, St. Peter

Description: Letter written in 1862 about the battle by a participant, Lieutenant Thomas van Etten.

https://collection.mndigital.org/catalog/nico:3386#/image/0?searchText=&redirect=true

M582

Dakota Conflict of 1862 Manuscripts Collections, 1862–1962

Minnesota Historical Society Microfilm, St. Paul

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/01166.xml

Description: Collects handwritten and typed accounts of participants in the US-Dakota War, including reminisces of the Battle of Birch Coulee. Not all accounts are dated; the accounts are from different dates. For information on the battle, see entries by: Amos B. Watson, Henry M. Huntington, Joseph Anderson, B.H. Goodell, Ezmon W. Earle, Hinhankaga (Joseph Courselle), and Justina Kreigher.

Secondary

Dahlin, Curtis A. "Looking for Relatives: Select Members of the Joseph R. Brown Burial Party." Minnesota's Heritage, no. 4 (July 2011):103–115.

Lass, William E. "Histories of the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862," Minnesota History 63, no. 2 (Summer 2012): 44–57.

Lewis, Charles. "Wise Decisions: A Frontier Newspaper's Coverage of the Dakota Conflict." American Journalism 28, no. 2 (Spring 2011): 48–80.

Web

Minnesota Historical Society. Birch Coulee Battlefield.

https://www.mnhs.org/birchcoulee

Minnesota Historical Society. Minnesota Tragedy: U.S.-Dakota War of 1862.

http://www.usdakotawar.org

Originally found at: http://www.usdakotawar.org/interactive-timeline

Minnesota Historical Society. History Topics.

http://libguides.mnhs.org/war1862

AV2011.45.25

U.S.-Dakota War of 1862 Oral History Project: Interview with Dallas Ross, May 1, 2011

Oral History Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St, Paul

http://collections.mnhs.org/cms/display.php?irn=11007778

Description: Dallas Ross was born in Granite Falls, Minnesota and is a member of the Upper Sioux Community. He discusses the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862

AV2011.45.31

U.S.-Dakota War of 1862 Oral History Project: Interview with LaVonne Swenson, February 15, 2011

Oral History Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

http://collections.mnhs.org/cms/display.php?irn=11007783

Description: LaVonne Swenson was born in Pipestone, Minnesota and is a member of the Lower Sioux Community. She lives on the Lower Sioux Reservation. She discusses the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862.

Related Images

Birch Coulee battlefield monument

Holding Location

Battle of Birch Coulee

Public domain

Holding Location

More Information

Joseph Renshaw Brown

Public domain

Holding Location

More Information

Joseph Anderson

Public domain

Holding Location

More Information

Wambditanka (Big Eagle)

Public domain

Holding Location

More Information

US Model 1841 "Mississippi" rifle

All rights reserved

Holding Location

More Information

Birch Coulee Monument, Renville County

Public domain

Holding Location

More Information

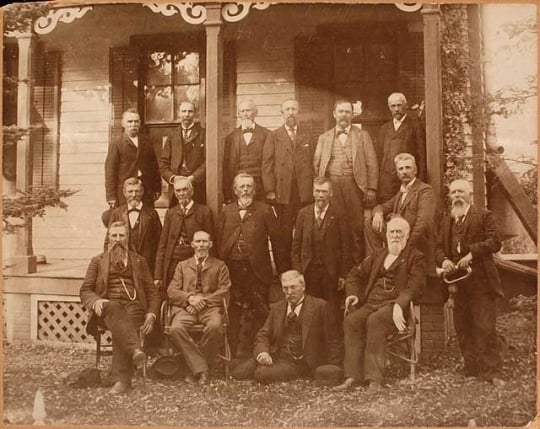

Survivors members of Company F, Sixth Minnesota Volunteer Infantry at the home of Captain Horace B. Wilson at Red Wing

Public domain

Holding Location

More Information

"Faithful Indians" Monument

Holding Location

"Faithful Indians" Monument

Holding Location

More Information

Marker at the site of the Battle of Birch Coulee

Holding Location

More Information

Related Articles

Turning Point

On the way to New Ulm, Dakota warriors spot a small group of Union forces making camp in a tactically vulnerable location, Birch Coulee. The next day, September 2, 1862, the Dakota attack at dawn and lay siege to the Union camp for more than thirty hours.

Chronology

August 17, 1862

August 31, 1862

Septem-ber 1, 1862

Septem-ber 2, 1862

Septem-ber 3, 1862

Septem-ber 26, 1862

December 26, 1862

1894

1900

1926

1998

2000

Bibliography

Anderson, Clayton, and Alan R. Woolworth, eds. Through Dakota Eyes: Narrative Accounts of the Minnesota Indian War of 1862. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1988.

Carley, Kenneth. The Dakota War of 1862. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2001.

Christgau, John. Birch Coulie: The Epic Battle of the Dakota War. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2012.

Folwell, William Watts. A History of Minnesota. Vol. II. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1961.

Related Resources

Primary

Anderson, Joseph, "Battle of Birch Coolie." Saint Paul Weekly Pioneer and Democrat, September 12, 1862.

"The Indian War." Saint Paul Weekly Pioneer and Democrat, September 12, 1862.

Barnes, T.C. Recollections of an Eventful Life. Typescript, 1917.

Boyd, Robert K. The Battle of Birch Coulee: A Wounded Man's Description of a Battle with the Indians. Eau Claire: Herges Printing Company, 1925.

———. Two Indian Battles: Battle of the Little Big Horn, June 25, 1876; Battle of Birch Coulee, Sept. 2 and 3rd, 1862. Eau Claire, 1928.

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/lb00030/lb00030-000001.pdf

———. "How the Indians Fought: A New Era in Skirmish Fighting, by a Survivor of the Battle of Birch Cooley." Minnesota History 11, no. 3 (September 1930): 299–304.

http://collections.mnhs.org/MNHistoryMagazine/articles/11/v11i03p299-304.pdf

———. "The Birch Cooley Monument." Minnesota History 12, no. 3 (September 1931): 297–301.

http://collections.mnhs.org/MNHistoryMagazine/articles/12/v12i03p297-301.pdf

Connolly, A.P. Minneapolis and the GAR: With a Vivid Account of the Battle of Birch Coulee, Sept. 2 and 3, the Battle of Wood Lake, Sept 23, the Release of the Women and Children Captives at Camp Release, Sept. 26, 1862. Minneapolis: A.P. Connolly, 1906.

Egan, James Joseph. The Battle of Birch Cooley. Renville County: Renville County Birch Cooley Memorial Association, 1927.

Holcombe, Return I., "A Sioux Story of the War: Chief Big Eagle's Account of its Important Incidents." St. Paul Pioneer Press, July 1, 1894.

http://www.startribune.com/july-1-1894-chief-big-eagle-speaks/166360646/

Sibley, Henry H. A Report to the Adjutant General on the Battle of Birch Coulee, September 4, 1862.

P694

Oversized C26

Robert Knowles Boyd Papers, 1925–1930

Manuscript Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

Description: Manuscripts by Boyd about the US-Dakota War. Also included is an oversized map of the Battle of Birch Coulee.

P841

Return I. Holcombe Papers, 1859–1916

Manuscript Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/00711.xml

Description: The papers of St. Paul journalist and historian, Return Holcombe, includes reminisces from Joseph R. Brown and Dr. Jared W. Daniels, and others.

M87

James T. Ramer Diary and Letter, 1862, 1865

Manuscript Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

Description: Diary kept by James T. Ramer, a Minnesota soldier, before and after the Battle of Birch Coulee.

Letter from Lieutenant Thomas van Etten, October 10, 1862

Manuscript Collection, Nicollet County Historical Society, St. Peter

Description: Letter written in 1862 about the battle by a participant, Lieutenant Thomas van Etten.

https://collection.mndigital.org/catalog/nico:3386#/image/0?searchText=&redirect=true

M582

Dakota Conflict of 1862 Manuscripts Collections, 1862–1962

Minnesota Historical Society Microfilm, St. Paul

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/01166.xml

Description: Collects handwritten and typed accounts of participants in the US-Dakota War, including reminisces of the Battle of Birch Coulee. Not all accounts are dated; the accounts are from different dates. For information on the battle, see entries by: Amos B. Watson, Henry M. Huntington, Joseph Anderson, B.H. Goodell, Ezmon W. Earle, Hinhankaga (Joseph Courselle), and Justina Kreigher.

Secondary

Dahlin, Curtis A. "Looking for Relatives: Select Members of the Joseph R. Brown Burial Party." Minnesota's Heritage, no. 4 (July 2011):103–115.

Lass, William E. "Histories of the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862," Minnesota History 63, no. 2 (Summer 2012): 44–57.

Lewis, Charles. "Wise Decisions: A Frontier Newspaper's Coverage of the Dakota Conflict." American Journalism 28, no. 2 (Spring 2011): 48–80.

Web

Minnesota Historical Society. Birch Coulee Battlefield.

https://www.mnhs.org/birchcoulee

Minnesota Historical Society. Minnesota Tragedy: U.S.-Dakota War of 1862.

http://www.usdakotawar.org

Originally found at: http://www.usdakotawar.org/interactive-timeline

Minnesota Historical Society. History Topics.

http://libguides.mnhs.org/war1862

AV2011.45.25

U.S.-Dakota War of 1862 Oral History Project: Interview with Dallas Ross, May 1, 2011

Oral History Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St, Paul

http://collections.mnhs.org/cms/display.php?irn=11007778

Description: Dallas Ross was born in Granite Falls, Minnesota and is a member of the Upper Sioux Community. He discusses the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862

AV2011.45.31

U.S.-Dakota War of 1862 Oral History Project: Interview with LaVonne Swenson, February 15, 2011

Oral History Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

http://collections.mnhs.org/cms/display.php?irn=11007783

Description: LaVonne Swenson was born in Pipestone, Minnesota and is a member of the Lower Sioux Community. She lives on the Lower Sioux Reservation. She discusses the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862.