Topics

Category

Era

Washburn A Mill

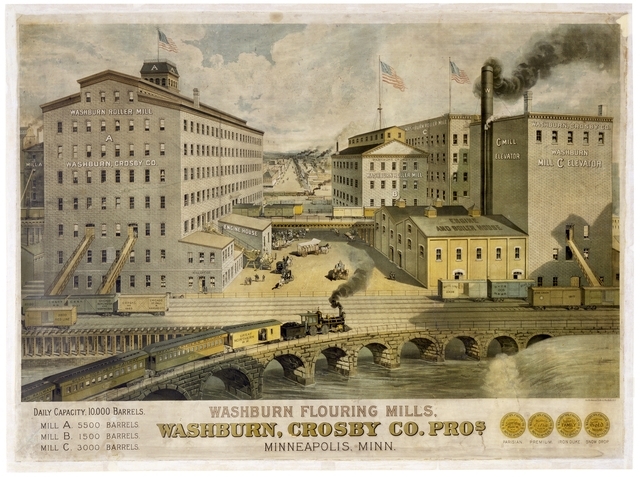

An advertisement shows the Washburn-Crosby flour-milling operation in Minneapolis ca. 1890, with the A Mill at left and the C mill elevator at right.

Washburn A Mill was one of twenty-six Minneapolis flour mills that lined the Mississippi River below St. Anthony Falls during the city’s industrial heyday. By the early 1900s, its company (Washburn-Crosby) was the leading flour miller in Minnesota. The historic building has had five reincarnations in its more than 150 years: an original mill (1874–1878); a rebuilt second mill (1880–1924); a renovated mill (1924–1965); a warehouse (1965–1990); and a museum operated by the Minnesota Historical Society (2003–present).

.

The first mill building was constructed by Cadwallader C. Washburn in 1874 at 701–729 First Street South and Portland Avenue. By 1877, Washburn had teamed up with John Crosby to form the Washburn-Crosby Company, and the partners made the A mill their headquarters. After a disastrous explosion and fire leveled that structure in 1878, they rebuilt.

The second mill was a seven-story rectangular structure with a rock limestone face and an interior reinforced with heavy beam construction. It had a flat roof topped with a one-story, three-bay-wide monitor, segmentally arched windows, and walls that tapered from five feet thick at their base to twenty inches thick at their top. While the 1880 building resembled the original mill from the outside, it benefited from new machinery inside: an automatic all-roller system with a capacity of 560,000 pounds (5,000 cwt). An office building and a seven-story wheat house, both attached to the mill itself, provided space for storage and administration.

The Washburn-Crosby Company adopted three groundbreaking technologies inside its new A mill. The land near Minneapolis produced winter wheat, a variety that was not commonly milled in the United States. This required new kinds of milling. The first problem was how to remove the dark, hard husks from the kernels of wheat. For this, Washburn hired Frenchman Edmund LaCroix to develop the middlings purifier: a machine that used jets of air to remove the husks from the flour.

The second major technological development was the introduction of the gradual reduction process. This process used porcelain, chilled iron, or steel rollers to gradually pulverize the purified middlings and integrate the gluten with the starch. The result of these breakthroughs was the production of a product, Gold Medal Flour, that Washburn-Crosby began advertising as the world’s best baking flour.

The final innovation came compliments of William de la Barre, who introduced and installed the Berhns Millstone Exhaust System. De la Barre’s technology solved the problem of flour dust that had led to the massive explosion that destroyed the first A Mill in 1880. Together, these three technological fixes helped make Washburn-Crosby (and its successor, General Mills), one of the biggest modern food companies in the world.

Over time, the Washburn A complex expanded to include a grain elevator (1905), an eleven-story utility building (1914), and a feed elevator (1928). The radio station WCCO broadcast from the utility building starting in 1924, and the Betty Crocker Test Kitchens operated there between 1924 and 1958.

After another fire gutted the mill in 1928, the interior was rebuilt, although the exterior remained largely unchanged. In the same year, Washburn-Crosby merged with three other companies to form GM, and production continued on the Minneapolis site under the new management. GM used the mill to continue manufacturing Gold Medal Flour while developing such dominant global products as Bisquick (1931), Wheaties (1924), Betty Crocker cake mix (1947), and Cheerios (1941).

Washburn A Mill stopped producing flour in 1965. Although it was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1971, and made a National Historic Landmark in 1983, the building had few tenants, and people without housing used it for shelter. It functioned as a warehouse until 1991, when yet another fire destroyed much of the interior. Shortly after that, the City of Minneapolis stabilized the remains of the mill, and the Minnesota Historical Society announced plans to turn the ruins into a museum. The completed site, Mill City Museum, opened to the public in 2003.

Bibliography

Adams, George R., and James B. Gardner. “Washburn A Mill Complex.” National Register of Historic Places nomination form (83004388), September 1978.

https://npgallery.nps.gov/NRHP/GetAsset/NHLS/83004388_text

Anfinson, John O. “Spiritual Power to Industrial Might: 12,000 Years at St. Anthony Falls.” Minnesota History 58, nos. 5–6 (Spring/Summer 2003): 252–269.

https://storage.googleapis.com/mnhs-org-support/mn_history_articles/58/v58i05-06p252-269.pdf

Anfinson, Scott F. “Unearthing the Invisible: Archaeology at the Riverfront.” Minnesota History 58 no.5–6 (Spring/Summer 2003): 320–331.

https://storage.googleapis.com/mnhs-org-support/mn_history_articles/58/v58i05-06p320-331.pdf

Atkins, Annette, “At Home in the Heart of the City.” Minnesota History 58, nos. 5–6 (Spring/Summer 2003): 286–304.

https://storage.googleapis.com/mnhs-org-support/mn_history_articles/58/v58i05-06p286-304.pdf

Curtis, F. E. “A Floury City.” Lippincott’s Magazine 33 (January 1884): 76–81.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Lippincott_s_Magazine/07IRAAAAYAAJ

Danbom, David B. “Flour Power: The Significance of Flour Milling at the Falls.” Minnesota History 58, nos. 5–6 (Spring/Summer 2003): 270–85.

https://storage.googleapis.com/mnhs-org-support/mn_history_articles/58/v58i05-06p270-285.pdf

General Mills: 75 Years of Innovation, Invention, Food, & Fun. General Mills, Inc., 2003.

Gray, James. Business Without Boundary: The Story of General Mills. University of Minnesota Press, 1954.

Kane, Lucille M. The Falls of St. Anthony: The Waterfall That Built Minneapolis. Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1987.

Larson, Henrietta M. The Wheat Market and the Farmer in Minnesota, 1858–1900. AMS Press, 1969.

Mill City Museum. Minnesota Historical Society.

https://www.mnhs.org/millcity

Roberts, Kate, and Barbara Caron. "To the Markets of the World": Advertising in the Mill City, 1880-1930.” Minnesota History 58 no.5–6 (Spring/Summer 2003): 308–319.

https://storage.googleapis.com/mnhs-org-support/mn_history_articles/58/v58i05-06p308-319.pdf

Smalley, Eugene V. “The Flour Mills of Minneapolis.” Century Illustrated 32 (September 1886): 37–47.

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015036865544&seq=5

Storck, John, and Walter D. Teague. Flour for Man’s Bread. University of Minnesota Press, 1952.

Watts, Alison. “The Technology That Launched a City: Scientific and Technological Innovations in Flour Milling During the 1870s in Minneapolis.” Minnesota History 57, no. 2 (Summer 2000).

https://storage.googleapis.com/mnhs-org-support/mn_history_articles/57/v57i02p086-097.pdf

Related Resources

Primary Sources

"Among the Ruins." Minneapolis Tribune, May 3, 1878.

"Around the Ruins." Minneapolis Tribune, May 4, 1878.

"After the Disaster." Minneapolis Tribune, May 8, 1878.

"Death and Destruction." Daily Globe, May 3, 1878

http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83025287/1878-05-03/ed-1/seq-1/

The Disaster." Daily Globe, May 4, 1878

http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83025287/1878-05-04/ed-1/

"The Great Disaster." Minneapolis Tribune, May 6, 1878.

P1455 and M600

Edwin H. Brown and Family Papers, 1866–1960

Manuscript Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

http://www.mnhs.org/library/findaids/p1455.xml

Description: Family papers document many aspects of the lives of members of the Brown, Hall, and Christian families, including the Minneapolis flour milling industry (1860s-1870s) and especially the Washburn A Mill explosion.

"A Terrible Disaster." Worthington Advance, May 9, 1878.

http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85025620/1878-05-09/ed-1/seq-1/

A/.D332

William De la Barre Papers, 1861–1924

Manuscript Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

Description: Papers relating to De la Barre, an engineer who was employed by Minneapolis waterpower owners and grain millers. There is information in the collection on the explosion of the Washburn A mill.

Secondary Sources

Bicha, Karl D. C.C. Washburn and the Upper Mississippi Valley. New York: Garland Publishing Inc., 1995.

"Explosion of the Washburn 'A' Mill." Eventually News 1, no. 27 (April 28, 1920): 1–7, 12.

Frame, Robert M. "'The Minneapolis Horror': The Great Mill Explosion of 1878." Old Mill News 9, no. 1 (January 1981): 8–11.

"The Great Mill Explosion and Fire of 1878." Hennepin County History 16–2, no. 62 (April 1956): 9–10.

Peckham, Stephen Farnum. The Dust Explosions at Minneapolis, May 2, 1878, and Other Dust Explosions. New York: n.p., 1908.

Pennefeather, Shannon M. ed. Mill City: A Visual History of the Minneapolis Mill District. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2003.

Taylor, R.J. The Washburn Mill: A Complete Solution of the Mysterious Causes of the Blowing Up of the Washburn Mill on the 2d Day of May, 1878. Minneapolis: Galesburg Printing and Publishing Company, 1880.

Wilson, Bonnie. "Eyewitness." Minnesota History 58, nos. 5 and 6 (spring/summer 2003): 250.

Web

Mill City Museum.

http://www.mnhs.org/millcity

National Register of Historic Places. Washburn A. Mill Complex, Minneapolis, 1971.

Originally found at: http://pdfhost.focus.nps.gov/docs/NHLS/Text/83004388.pdf

Related Images

Washburn-Crosby Mills advertisement

An advertisement shows the Washburn-Crosby flour-milling operation in Minneapolis ca. 1890, with the A Mill at left and the C mill elevator at right.

Workers operate flour-roller mills inside Washburn A Mill, ca. 1875.

Workers operate flour-roller mills inside Washburn A Mill, ca. 1875. Photograph by William H. Jacoby.

Public domain

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

Interior of Washburn A Mill, ca. 1875.

Interior of Washburn A Mill, ca. 1875. Photograph by William H. Jacoby.

Holding Location

Minnesota Historical Society

Workers seal barrels of flour inside Washburn A Mill, ca. 1875

Workers seal barrels of flour inside Washburn A Mill, ca. 1875. Photograph by William H. Jacoby.

Public domain

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

Flour mill row in Minneapolis ca. 1877

Flour mill row in Minneapolis ca. 1877, before the 1878 flour-dust explosion. Pictured are, left to right: Washburn A Mill, Crown Mill, Empire Mill, Pillsbury B Mill, Excelsior Mill, a paper mill, and Northwestern Mill.

Public domain

Holding Location

Articles

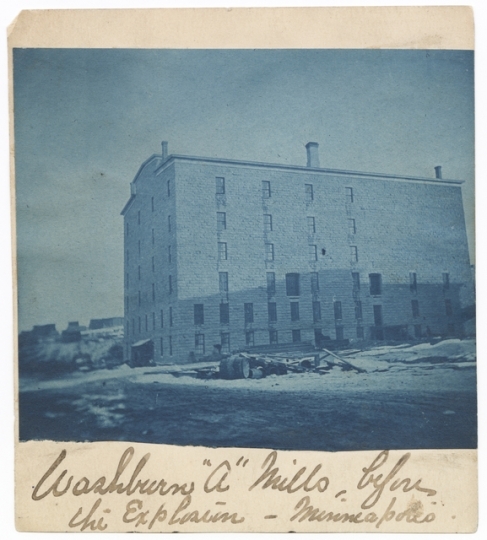

Cyanotype of Washburn A Mill, ca. 1877

Cyanotype of Washburn A Mill, ca. 1877, before the 1878 flour-dust explosion.

Holding Location

Articles

The ruins of Washburn A Mill

The ruins of Washburn A Mill and other mills after a flour-dust explosion, 1878.

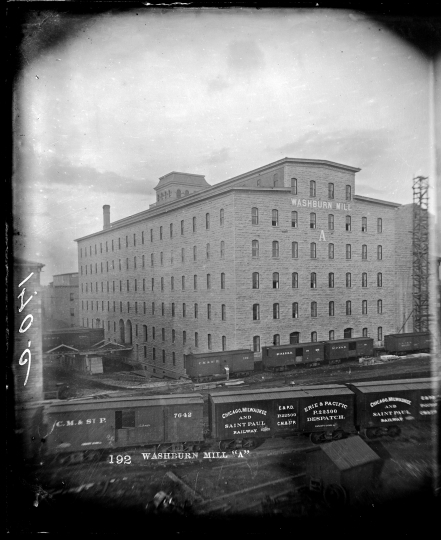

Washburn A Mill, ca. 1885.

Washburn A Mill, ca. 1885.

Holding Location

Articles

Washburn A Mill, 1905.

Washburn A Mill, 1905.

Holding Location

Articles

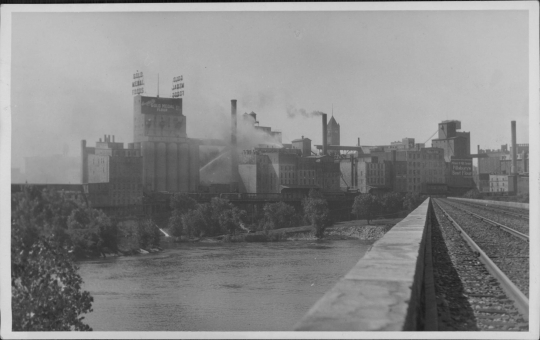

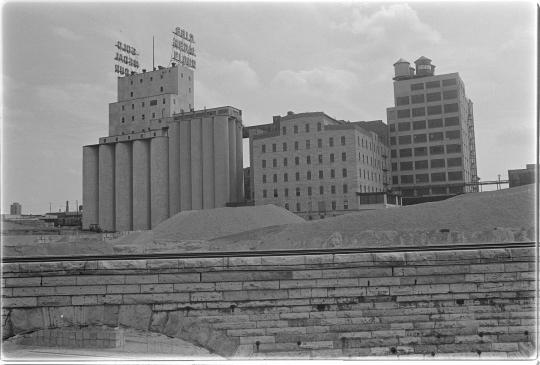

Washburn A Mill complex in Minneapolis

Washburn A Mill complex in Minneapolis, photographed by C. J. Hibbard between 1914 and 1927.

Holding Location

Articles

Washburn A Mill during a fire, September 21, 1928

Washburn A Mill during a fire, September 21, 1928.

Holding Location

Articles

Washburn A Mill and neighboring buildings, ca. 1950.

Washburn A Mill and neighboring buildings, ca. 1950.

Holding Location

Articles

Abandoned Washburn A Mill, 1976.

Abandoned Washburn A Mill, 1976. Photograph by Steven W. Plattner.

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

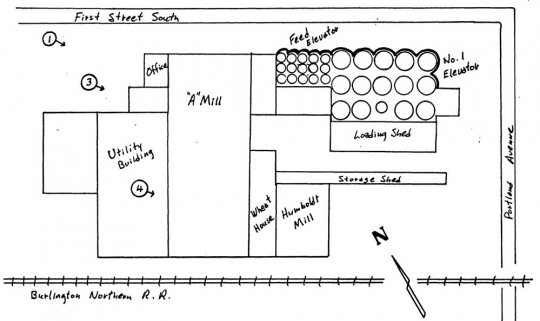

Diagram of the Washburn A Mill

Diagram of the Washburn A Mill complex as it appeared in 1978. Sketch by G. R. Adams included in the National Register of Historic Places nomination form submitted in 1978.

The Washburn A Mill complex, Minneapolis, June 1978.

The Washburn A Mill complex, Minneapolis, June 1978. Visible are the elevators, the mill building (the northeast end and northwest side), offices, and a utility building. Photograph by George R. Adams.

Interior of Washburn A Mill’s fifth floor

Interior of Washburn A Mill’s fifth floor, showing the roller mills. Photograph by George R. Adams, June 1978.

Washburn A Mill on fire, February 1991.

Washburn A Mill on fire, February 1991.

Washburn A Mill ca. 1991, after a fire.

Washburn A Mill ca. 1991, after a fire.

The rear side of Mill City Museum

The rear side of Mill City Museum, closest to the Mississippi River, with the iconic Gold Medal Flour sign topping the complex. Photograph by Wikimedia Commons user McGhiever, June 16, 2014. CC BY-SA 4.0

%2c_2nd_Street%2c_Mill_District%2c_Minneapolis%2c_MN_-_51781710680.jpg)

The front facade of Mill City Museum

The front facade of Mill City Museum in Minneapolis. Photograph by Warren LeMay, September 25, 2021. CC BY-SA 2.0

The side of Mill City Museum closest to the Mississippi River

The side of Mill City Museum closest to the Mississippi River, with the iconic Gold Medal Flour sign topping the complex. Photograph by Wikimedia Commons user Runner 1928, March 26, 2017. CC BY-SA 4.0

Related Articles

Turning Point

The commitment of the Washburn-Crosby Company to innovate in the aftermath of the 1878 explosion leads to the dramatic growth of the flour industry in Minneapolis. Borrowing best practices and cutting-edge technology from around the world, the company turns what had been an average building into an incubator for a global brand and diversified food giant (General Mills).

Chronology

1874

1878

1880

1903

1916

1921

Betty Crocker is created to help sell products by answering questions from consumers about cooking with Washburn-Crosby flour.

1924

Washburn-Crosby introduces Wheaties. It is the first cold breakfast cereal created by a Minneapolis milling company.

1924

The mill sustains significant damage due to a fire, and the interior is rebuilt.

1928

The Washburn-Crosby Company becomes General Mills by merging with four other mills.

1965

The mill stops production and is used as a warehouse.

1971

The mill is added to the National Register of Historic Places.

1983

Washburn A Mill becomes a National Historic Landmark.

1991

Another fire hits the mill and leaves the building largely in ruins. What remains is structurally reinforced, and the Minnesota Historical Society makes plans to turn the site into a museum.

2003

The Minnesota Historical Society opens Mill City Museum, which tells the story of how Minneapolis became the flour-milling capital of the world.

Bibliography

Adams, George R., and James B. Gardner. “Washburn A Mill Complex.” National Register of Historic Places nomination form (83004388), September 1978.

https://npgallery.nps.gov/NRHP/GetAsset/NHLS/83004388_text

Anfinson, John O. “Spiritual Power to Industrial Might: 12,000 Years at St. Anthony Falls.” Minnesota History 58, nos. 5–6 (Spring/Summer 2003): 252–269.

https://storage.googleapis.com/mnhs-org-support/mn_history_articles/58/v58i05-06p252-269.pdf

Anfinson, Scott F. “Unearthing the Invisible: Archaeology at the Riverfront.” Minnesota History 58 no.5–6 (Spring/Summer 2003): 320–331.

https://storage.googleapis.com/mnhs-org-support/mn_history_articles/58/v58i05-06p320-331.pdf

Atkins, Annette, “At Home in the Heart of the City.” Minnesota History 58, nos. 5–6 (Spring/Summer 2003): 286–304.

https://storage.googleapis.com/mnhs-org-support/mn_history_articles/58/v58i05-06p286-304.pdf

Curtis, F. E. “A Floury City.” Lippincott’s Magazine 33 (January 1884): 76–81.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Lippincott_s_Magazine/07IRAAAAYAAJ

Danbom, David B. “Flour Power: The Significance of Flour Milling at the Falls.” Minnesota History 58, nos. 5–6 (Spring/Summer 2003): 270–85.

https://storage.googleapis.com/mnhs-org-support/mn_history_articles/58/v58i05-06p270-285.pdf

General Mills: 75 Years of Innovation, Invention, Food, & Fun. General Mills, Inc., 2003.

Gray, James. Business Without Boundary: The Story of General Mills. University of Minnesota Press, 1954.

Kane, Lucille M. The Falls of St. Anthony: The Waterfall That Built Minneapolis. Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1987.

Larson, Henrietta M. The Wheat Market and the Farmer in Minnesota, 1858–1900. AMS Press, 1969.

Mill City Museum. Minnesota Historical Society.

https://www.mnhs.org/millcity

Roberts, Kate, and Barbara Caron. "To the Markets of the World": Advertising in the Mill City, 1880-1930.” Minnesota History 58 no.5–6 (Spring/Summer 2003): 308–319.

https://storage.googleapis.com/mnhs-org-support/mn_history_articles/58/v58i05-06p308-319.pdf

Smalley, Eugene V. “The Flour Mills of Minneapolis.” Century Illustrated 32 (September 1886): 37–47.

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015036865544&seq=5

Storck, John, and Walter D. Teague. Flour for Man’s Bread. University of Minnesota Press, 1952.

Watts, Alison. “The Technology That Launched a City: Scientific and Technological Innovations in Flour Milling During the 1870s in Minneapolis.” Minnesota History 57, no. 2 (Summer 2000).

https://storage.googleapis.com/mnhs-org-support/mn_history_articles/57/v57i02p086-097.pdf

Related Resources

Primary Sources

"Among the Ruins." Minneapolis Tribune, May 3, 1878.

"Around the Ruins." Minneapolis Tribune, May 4, 1878.

"After the Disaster." Minneapolis Tribune, May 8, 1878.

"Death and Destruction." Daily Globe, May 3, 1878

http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83025287/1878-05-03/ed-1/seq-1/

The Disaster." Daily Globe, May 4, 1878

http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83025287/1878-05-04/ed-1/

"The Great Disaster." Minneapolis Tribune, May 6, 1878.

P1455 and M600

Edwin H. Brown and Family Papers, 1866–1960

Manuscript Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

http://www.mnhs.org/library/findaids/p1455.xml

Description: Family papers document many aspects of the lives of members of the Brown, Hall, and Christian families, including the Minneapolis flour milling industry (1860s-1870s) and especially the Washburn A Mill explosion.

"A Terrible Disaster." Worthington Advance, May 9, 1878.

http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85025620/1878-05-09/ed-1/seq-1/

A/.D332

William De la Barre Papers, 1861–1924

Manuscript Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

Description: Papers relating to De la Barre, an engineer who was employed by Minneapolis waterpower owners and grain millers. There is information in the collection on the explosion of the Washburn A mill.

Secondary Sources

Bicha, Karl D. C.C. Washburn and the Upper Mississippi Valley. New York: Garland Publishing Inc., 1995.

"Explosion of the Washburn 'A' Mill." Eventually News 1, no. 27 (April 28, 1920): 1–7, 12.

Frame, Robert M. "'The Minneapolis Horror': The Great Mill Explosion of 1878." Old Mill News 9, no. 1 (January 1981): 8–11.

"The Great Mill Explosion and Fire of 1878." Hennepin County History 16–2, no. 62 (April 1956): 9–10.

Peckham, Stephen Farnum. The Dust Explosions at Minneapolis, May 2, 1878, and Other Dust Explosions. New York: n.p., 1908.

Pennefeather, Shannon M. ed. Mill City: A Visual History of the Minneapolis Mill District. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2003.

Taylor, R.J. The Washburn Mill: A Complete Solution of the Mysterious Causes of the Blowing Up of the Washburn Mill on the 2d Day of May, 1878. Minneapolis: Galesburg Printing and Publishing Company, 1880.

Wilson, Bonnie. "Eyewitness." Minnesota History 58, nos. 5 and 6 (spring/summer 2003): 250.

Web

Mill City Museum.

http://www.mnhs.org/millcity

National Register of Historic Places. Washburn A. Mill Complex, Minneapolis, 1971.

Originally found at: http://pdfhost.focus.nps.gov/docs/NHLS/Text/83004388.pdf

%2c_2nd_Street%2c_Mill_District%2c_Minneapolis%2c_MN_-_51781710680.jpg?width=200&height=200&name=Washburn_A_Mill_(Mill_City_Museum)%2c_2nd_Street%2c_Mill_District%2c_Minneapolis%2c_MN_-_51781710680.jpg)